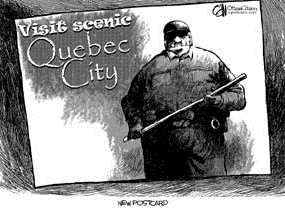

In November 1999 in Seattle, the WTO, until then a virtually unknown institution to most people, was the star attraction for several days of televised street theatre. There have since been repeat performances at the World Bank/IMF meetings in Washington the following April and in Prague in September of last year, as well as at other international meetings in Bangkok (at UNCTAD X) and Montreal (for the Biosafety Protocol) and, most recently, at the Summit of the Americas get-together in Quebec City in April. The mobilization of protest demonstrations against international institutions didn’t start in Seattle. There were demonstrations at the WTO meeting in Geneva in 1998 and at Bank/Fund meetings throughout the 1990’s. But the scale and the complexity of the choreography and drama at Seattle were unprecedented and may well have established a new trend.

But even if it has (a question I’ll return to below) it would be wrong to assess the implications of the anti-globalization movement solely on the basis of its visible manifestation on television. In fact, the invisible impact of the NGO’s on the international policy processes and institutions may turn out to be more important over the longer run, as I’ll also try to show.

First, however, it is essential to provide some context for a discussion that will largely deal with the role of non-governmental organizations or NGO’s. I do not intend to enter into the definitional morass surrounding NGO’s except to distinguish between advocacy NGO’s and NGO’s whose main function is to provide services in development programs. The advocacy NGO’s have created international networks which can be broadly categorized as either “mobilization networks,” whose chief objective is to rally support for dissent at a specific event, or “technical/legal networks,” which designed to provide information with respect to a specific policy issue or policy-making process. A third group of NGO’s might be termed a “virtual secretariat” for developing countries. Given the limits of time and space I shall not be dealing with this group which is dedicated to providing information, ranging from technical research and policy papers to activist policy advocacy for Southern countries in the WTO and the Bretton Woods institutions. Suffice to say, however, that this “virtual secretariat” is playing an increasingly important role in promoting a proactive Southern agenda, especially in the WTO, while some of the transnationals in the secretariat are also active in mobilization.

The main objective of the mobilization networks is to heighten public awareness of the target international institution’s role in globalization and, by doing so, change its agenda and mode of operation—or, in the case of the more extreme members of the coalition, to shut it down. Though these networks are loosely knit coalitions of very disparate groups an analysis of the networks at Seattle, Washington, Bangkok and Prague show that a significant proportion are environmental, human-rights and gender-rights NGO’s.

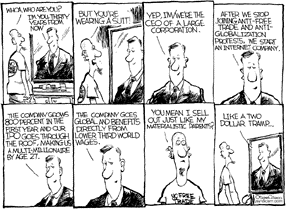

One must be wary of the view (often stressed by the NGO’s themselves) that these loose and diverse coalitions represent a new form of globalized participatory democracy on the Internet. That may be partly the case, but the most significant development facilitated by the Internet—and vividly demonstrated in Seattle—has been the emergence of a new service industry: the business of dissent. And there is a business centre—call it dissent.com—that is very effectively operated by a core group of NGO’s headed by a new breed of policy entrepreneurs. It’s important to stress that the dissent industry is largely a product of the Internet revolution. Inexpensive, borderless, real-time networking provides advocacy NGO’s—especially those headed by policy entrepreneurs—with economies of scale and also of scope by linking otherwise widely disparate groups that share one common theme.

As is the case for all innovations there are also important positive feedback loops. An NGO network established at the Rio Summit in 1992 was used by American, Canadian and Mexican anti-NAFTA advocacy groups and this experience was vital to mobilizing the fight against the Multilateral Agreement on Investment (MAI). Similarly, the lessons from the MAI were put to use in preparing for Seattle and the Seattle experience was helpful in planning for Washington and so on—and on.

The key asset of dissent.com is its ability to use the media to get out the message, though even when the message and the media are combined with money (from mass mailings and foundations—mainly American) the viability of the new business will depend on the saleability of its product: anti-globalization. I’ll return to this later.

Tracking the NGO’s at Seattle, Washington and Prague on the Internet suggests that a core group is central to managing the protests, crafting the message and organizing the circulation of “sign on” lists. This core or headquarters of dissent.com included Ralph Nader’s Public Citizen and Global Trade Watch in the US; Corporate Watch and ATTAC (France), Corporate Europe Observatory (Amsterdam), Oxfam (UK and Belgium); and the Third World Network of Malaysia, the most prominent transnational Southern NGO. A number of other NGO’s were involved in facilitating the demonstrations in Seattle, Washington and Prague. Thus the Direct Action Network (DAN) with offices in California and New York began as a coalition of activist groups dedicated to shutting down the WTO Ministerial. DAN was inspired by Peoples Global Action (PGA), which was formed in Geneva for the first WTO Ministerial in 1998 and organized a “carnival against capitalism” in the city of London on June 18, 1999, which deteriorated into violence, rioting and vandalism in the financial district. Global Exchange, based in San Francisco, coordinates activities with DAN and Global Trade Watch. INPEG (Prague) was formed to plan and carry out a week of protest in Prague from September 18-28, 2000. The European groups were anxious to replicate Seattle, which they regarded as an impressive “model.” These coordinating and organizing NGO’s provide training sessions for non-violent direct action as well as other matters such as legal rights and medical first aid.

Coordinating and organizing the demonstrations is only one function of dissent.com. Another, of equal or great importance, is creating the libretto for the street operas and the TV sound bites that inevitably accompany the counter-meetings. Since the networks are so diverse both in mission and location the message must carry a simple, common theme: anti-globalization/pro-democracy. The charge is that the WTO (or the Fund or the World Bank) is dominated by the interests of transnational corporations that harm the environment and increase inequality and that their rules and procedures are undemocratic. Examples of sound bite versions at Seattle were “Fix it or nix it”; and after Seattle, “Shrink it or sink it” and at Washington “Defund the Fund! Break the Bank! Dump the Debt!” These slogans circulate on the Internet and one can hear echoes in newspaper and television interviews, at student meetings, and so on. As soon as a book or pamphlet is published summaries are circulated and the message is spread. The Internet clearly is having an unprecedented impact on the diffusion of information and the process has just begun.

The main objective of mobilization networks is to influence public opinion and by that route initiate change in the policy processes of the international institutions. Has the dissent industry been successful? In the case of the WTO, I would argue that it’s too early to tell. But if one reviews the impact of NGO’s on the World Bank the answer would certainly be “yes, indeed.”

A major change in the World Bank’s operations is documented in a case study of the Narmada dam project in India, which was financed by the Bank until 1993 when the loan agreement was cancelled. (See J. Sen, “A world to win—but whose world is it anyway?”, in J. W. Foster and A. Anand, eds. Whose World is it Anyway? Ottawa: UN Association of Canada, 1999.) The cancellation followed a carefully orchestrated decade-long international campaign by NGO’s in the US, Brazil, Europe and India. Launched by American environmental NGO’s in 1982, the campaign involved lobbying Congress, mobilizing Brazilian NGO’s and member governments of the Inter-American Development Bank to halt funding of infrastructure projects in Latin America. By the end of the 1980’s the coalition of environmentalist and human rights activists began to focus on Asia and particularly on the Narmada dam, a priority for the Indian government from the time of Nehru. Oxfam (UK) played a major role in lobbying the World Bank and linking with the newly emerging NGO’s in India and with American, European, Japanese and Australian networks of environmental and human rights groups who lobbied not only the World Bank but also demanded that their own governments stop funding such projects. The campaign was concluded in 1993—at least so for as the Narmada dam was concerned.

But this particular campaign and continuing lobbying and demonstrations had a far wider effect on the Bank’s program. Thus, for example, in 1993 the Bank established the position of Vice President of Environment and Sustainable Development and expanded its concept of development to cover three goals: economic (which included growth, equity and efficiency); social (covering objectives such as empowerment, social cohesion, and institutional development); and ecological (which concerned ecosystems, biodiversity, carrying capacity, and the like). This remarkable change, which has been repeatedly and severely criticized by the neo-liberal press, was not internally driven but is a consequence of the NGO networks’ efforts, not simply their demonstrations but the complex, coordinated transnational multi-track strategy they devised. As a further consequence of these efforts, the World Bank today engages NGO’s in operational collaboration, research collaboration and broad policy dialogue. (See, for instance, the report of the NGO commission on dams, posted on the World Bank’s website: https://www.worldbank.org/html/extdr/ pb/dams.) The Bank’s extensive engagement with NGO’s is not supported by many developing country governments, which exacerbates a growing North-South divide over other issues.

Does the World Bank’s experience presage similar developments in the WTO? There are many reasons to think not, including the sheer size of the Bank (7,000+ staff compared with the WTO’s 500), which makes it more “porous” to engagement with outsiders and more susceptible to political pressure, especially by the US Congress, as well as the much more coherent policy template of the trade system. Still, the WTO was not immune to the NGO networks and the demonstrations in Geneva in 1998 led to more rapid de-restriction of documents and to the March 1999 WTO symposia on Trade and the Environment and Trade and Development, which included such a large number of NGO’s that one European official rejected the term “global civil society” and proposed instead “the new globerati”! And whereas NGO’s had to attend the Marrakesh Ministerial meeting in 1994 disguised as reporters nearly 700 NGO’s from 54 countries were accredited at Seattle.

But despite the orchestrated and sometimes violent protests in Seattle the claims of the NGO’s to have shut down the meeting don’t stand up to closer analysis. Even without the protests, the wide North-South divide within the WTO in the aftermath of the Uruguay Round and the substantial trans-Atlantic division between the US and the EU on a number of key issues ensured that any agreement, however fudged, would be difficult to achieve. The absence of high-profile business lobbies in Seattle meant that key players in the trade game were not present, while for its part the AFL-CIO was out in force, mainly in pursuit of domestic political goals. The coup de grâce for Seattle came from President Bill Clinton’s statement about labour standards enforced by sanctions (again, for domestic political reasons). Nonetheless, one should not discount the aftereffects of the Turtle-Teamster alliance, which so angered many Southern countries and left the unfortunate and false impression that these two “trade and …” issues were inextricably linked.

In sum, the demonstrations in Seattle—the “visible” manifestation of the NGO networks— obviously cannot be dismissed as inconsequential. But neither can the triumphalist claim of some mobilization groups that Seattle was the “big bang” of a new global social movement be substantiated. Nevertheless, the “invisible” impact of these new actors, which is already underway, is certainly worthy of examination. The NGO’s involved are what I have termed “technical/legal” and are predominantly environmental and human rights advocates. Some may join the demonstrators outside but for the most part they prefer to operate inside.

The lead role of environmentalists in the policy process is manifest in both the domestic and international arenas. In the industrialized countries, “regulatory inflation,” as the OECD calls it, began in the 1970’s with the rise of the consumer and environmental NGO’s in the US and Canada and the movement spread to Europe. In the international arena two conferences are landmarks in the emergence of the environment as a major global issue: the Conference on the Human Environment in Stockholm in 1972 and the Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED) in Rio de Janeiro in 1992. Rio marked the real departure. Earlier multilateral treaties did not provide official access to NGO participation. Rio changed that in a most dramatic fashion. Nine thousand NGO’s were accredited and today NGO’s are actively involved in the most significant of the 200-plus multilateral environmental agreements (MEA’s). At policy conferences they have access to working drafts of documents, sometimes circulate their own drafts, are allowed to address meetings and are prominent in delegations of many (mainly OECD) countries. Further, after Rio, UNCED asked the UN to formalize the rules for NGO participation and since that time the UN has increasingly expanded the formal involvement of NGO’s in all its activities. Thus between 1948 and 1998 the number of NGO’s given consultative status increased from 41 to 1350, most of which are Northern, mainly environmental, human-rights and women’s groups. Because the NGO’s helped create a constituency for UN activities the interaction was, for the most part, considered mutually beneficial.

The NGO networks established at Rio have expanded and intensified over the 1990’s. UN conferences proved to be very important in building networks not only in the environmental but Cam Cardow also in the human rights field. For many in the UN institutions, getting a high turnout of NGO’s at a conference is considered a badge of success. Indeed one could say, only half in jest, that the transnational environmental movement is largely the result of conference-building measures!

Why have the environmental NGO’s (ENGO’s) been so successful in assuming such a significant role? For a number of reasons: First, the ENGO’s got a head start in the domestic arena and thus were ready to go global. In many respects, international environmental policy was (and is) uncharted territory, fraught with uncertainty and subject to continuing change as new scientific information is produced. There is no clear, widely accepted theoretical model as there is in the economics of trade and no politically comforting reciprocity to enhance the negotiation process. A “model of ecology” does not rest on accepted doctrine and the policy issues are cross-cutting and must be analyzed within a multi-disciplinary framework. For all these reasons technical knowledge, which many ENGO’s possess in greater depth than many governments or corporations, is a key strategic asset. In Isaiah Berlin’s terminology, the ENGO’s are hedgehogs who know one big thing while governments are foxes, who know many things. The ENGO’s are more flexible in adapting to ongoing and diffuse change in ideas and knowledge while governments are prone to inertial decision-making. Thus, for governments and intergovernmental institutions dealing with global environmental issues, technical advice and access to global networks can be extremely valuable.

This last point needs stressing. Although their “home base” or place of origin is primarily American the largest and most active ENGO’s have affiliates around the world. Greenpeace in Amsterdam has organizations in 20 countries; Friends of the Earth in 50; the World Wildlife Fund in 28. The Sierra Club has an entire department dedicated to international issues and networking. Another feature of these ENGO’s is their wealth. The assets of the Environmental Defence Fund are over $18 million; Greenpeace US $15 million; and WWF, $90 million. Of course, it is important to put these numbers in context: They are dwarfed by the resources controlled by multinational enterprises.

The most powerful transnational ENGO’s are North American but there are also many European and even some developing country ENGO’s that were formed in the late 1980’s and 1990’s. These are part of the global networks but the networks are by no means homogeneous. Indeed there is a considerable North-South divide on many environmental policy issues (see below) and also some significant trans-Atlantic differences.

The environmental movement of the 1970’s, which was very different from the conservation movement of the early 20th century, grew out of the anti-nuclear protests. Thus Greenpeace was formed at a meeting in Vancouver in 1970 to demonstrate against nuclear testing in the North and by 1972 it was in France protesting against French nuclear testing. The diffusion of protest had begun and, of course, it has accelerated with the use of the Internet. In Europe, this advocacy route to influencing the process of policy-making was not so widespread. Probably because of differences in the political systems, a political party route was chosen instead. By the early 1980’s the Green Party was in the Bundestag and today there are social democratic and green coalitions in three European countries (Germany, France and Finland) as well as an increasing number in the European Parliament. Green NGO’s did arise though mainly in the UK and the Northern countries.

There is one very significant difference between North American and European NGO’s: The North Americans place far greater emphasis on a legalistic approach while the Europeans are more social-democratic in approach, as are the green parties. One could say that a North American ENGO’s rallying cry was “let’s litigate” while the Europeans’ is “let’s regulate”—whether at home or in Brussels. Because of its potential for impeding negotiations concerning global environmental issues, this trans-Atlantic difference is worth a brief digression.

When last winter’s Hague negotiations on the Kyoto Protocol broke down, the Americans blamed the Europeans and the Europeans blamed the Americans. As former US Environmental Protection Agency head William Reilly observed in an article shortly after the conference, American critics see European policy on environmental issues as being designed to reduce the competitiveness of US industry and favour less competitive European firms. A much more comprehensive version of this conspiracy theory attributes European pro-environmental policies not only to a desire to protect North European industries but also to the interventionist bent of the social democratic and green parties and the European NGO’s, who are provided considerable funding by Germany, the Scandinavian countries and the EU. This conservative critique of environmentalism also includes the charge that what is really at issue is a mainly European plan for global governance, a collectivist approach that must be rejected not only because it forswears market mechanisms but also because it would profoundly undermine American sovereignty. It goes without saying that if the US and the EU are not able to forge some kind of compromise, at least in the WTO, the legislative route does not appear too promising over the foreseeable future.

Just as the environmental stance of European governments reflects broader political and cultural concerns, the litigious bent of the American ENGO’s is deeply rooted in the American legal system, most specifically in the postwar Administrative Procedures Act (APA). The basic principles of the APA were transferred to the GATT in Article X and then vastly expanded in the Uruguay Round. Essentially the APA principles concern transparency, including publication of all relevant laws and regulations, and basic procedural rules stressing the right of private actors to participate in rule-making and in the monitoring and enforcing of regulatory law. The APA was in effect based on the view that bureaucratic power must be curtailed, a reaction to the expansion of government under the New Deal and the War. While all European countries also adopted administrative procedures laws, as did Japan under the Occupation, these laws provided much more room for administrative discretion and much less room for participation by private actors in the rule-making process.

Just as the APA was embedded in the trading system it has also been incorporated into many of the MEA’s through procedural rules that opened the door to ENGO participation. The question now posed with increasing insistence by the ENGO’s is “If participation is in the ‘spirit’ of the MEA’s, why should it not also be in the spirit of the WTO?” And since the legislative route to inclusion is at present blocked, then why not take the legalistic route? In fact, North American NGO’s are already asking for the right to present amicus curiae briefs under the Dispute Settlement mechanism.

This push for amicus rights was sparked by a number of disputes concerning environmental issues in the WTO. The Southern countries are uniformly opposed to the demand for amicus submissions, arguing that it would erode the rights of governments and—since they are hardly rich in legal resources—tilt the system against them. There is the view, moreover, that opening the door to ENGO’s would be just the first step and that lawyers acting on behalf of corporations and other interest groups or even in their own interest would be next in line. This would transform the dispute system into a largely litigious policy-making process. Because WTO law is often deliberately vague or ambiguous, the panels and the Appellate Body will be making law, not just interpreting it, and the rules of the WTO will evolve as a result of litigation, not negotiation. In the recent case concerning asbestos the Appellate Body decision concerning amicus briefs has created a furore of dispute among member governments—and was, indeed, supported only by the US.

Given the current state of affairs in the WTO, however, there seems little prospect of launching a genuine debate on the dispute settlement arrangements (where the questions concerning amicus presentations are essentially political and not procedural) let alone a negotiation on trade and the environment. The legalistic route will therefore remain the only game in town. A number of American legal scholars have presented carefully reasoned arguments for this track and one, Richard Shell, has even coined the term “participatory legalism”—which will seem a trifle odd in countries where law suits don’t make policy (or determine elections!). Countries lacking the requisite legal resources will feel the same way. After all, with four per cent of the world’s population the US has 50 per cent of the world’s lawyers.

Another interesting “invisible” legal track has nothing directly to do with the environment but may eventually have a significant impact on WTO rules concerning both economic and social regulatory policies. It concerns the proposals by human rights NGO’s and a growing number of lawyers, that “customary international law” on human rights should prevail over international trade law, i.e. should override those WTO rules which are alleged to violate basic human rights as defined by the UN Charter. This proposal has generated a storm of controversy about the role and indeed the meaning or even existence of customary international law (CIL) and a spate of articles by American legal experts warning of the implications of what they see as a move to global governance. But it has also created a confrontation between the WTO and the High Commission for Human Rights.

In June 2000 the UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights released a draft report prepared at its request which charged, inter alia, that the WTO excludes developing countries from its decision-making processes (which were described in the report as a “nightmare”) and that in particular the TRIPS agreement (trade-related intellectual property) violated basic rights, including the right to enjoy the benefits of scientific progress, the right to health and the right to food. The secretariat of the WTO firmly rejected the report as inaccurate and biased. But it was hailed as a major breakthrough by human rights and anti-globalization NGO’s.

The report echoes the main thrust of the UN Committee’s statement to the Seattle Ministerial, which argues that it is essential “to ensure that human rights principles are fully integrated in future negotiations in the WTO” and that human rights impact studies are undertaken before any further negotiations are launched. Just as the ENGO’s argue that the overall objective of the WTO should be sustainable development, the UN Committee asserted that trade liberalization is a means not an end and that the objective of the WTO is “human well-being to which the international human rights instruments give legal expression” and it cites as “proof” the 1993 Vienna Convention.

A key player in the human rights movement—as he also was at Seattle—was Malini Mehra, head of PDHRE (People’s Decade of Human Rights Education), an NGO founded in 1988 which has consultative status at the UN. Based in New York, PDHRE established a London office in 1999. Originally dedicated to community-level education on economic, social and cultural rights, like many other service NGO’s PDHRE began to shift to international economic issues in the second half of the 1990’s and cofounded INCHRITI (International NGO Committee on Human Rights on Trade and Investment) a transnational NGO network linking NGO’s from Asia, Africa, North America and South America. Both PDHRE and INCHRITI played important roles in promoting the Sub Commission’s Report and planning a continuing campaign to establish the primacy of human rights over trade law. One intriguing aspect of this new development is to substitute the human rights approach for the trade and labour standards proposals of the unions—which Malini Mehra describes as “piecemeal (and) self-serving.” The inclusion of labour standards in the WTO has been fiercely criticized by all the Southern countries, but perhaps these NGO’s believe their broader approach can garner more international support. They are pragmatic enough to understand, however, that their argument for turning the WTO into a human rights organization by adopting a change in its preambular “mission statement” is disingenuous, to say the least. A better route would be, as Mehra puts it, a “serious re-consideration of the WTO’s Dispute Settlement Understanding” to mitigate the enforcement gap. And perhaps hyperlexia is migrating to the Continent: ATTAC, the rapidly growing and high-profile French NGO, has also announced that a major priority is to ensure that the WTO dispute mechanism recognizes the primacy of international law!

Because the efforts of the technical/legal NGOs to effect change in the mandate and operations of the WTO are largely invisible to the general public and because they are alien to the trade policy community there may be a tendency to dismiss them: After all, lawyers will be lawyers so why bother to parse all the fine print in Appellate Board fundings or legal journals or UN conventions and declarations? This would be unwise. It would be far better to launch a discussion in the WTO about the broader implications of amicus briefs, customary international law and the relationship of the WTO with UN bodies. Alas, there is at present no forum for doing so. But before discussing how the WTO might proceed I want to deal with one more pertinent development: the counter-currents already visible in the anti-globalization tidal wave.

One aim of the dissent industry is to heighten public awareness of the anti-globalization issues and the role of international organizations in fostering globalization. In that regard they have been successful. But they no doubt did not anticipate one of the consequences of success, a consequence the main mobilization NGO’s deplore—the attraction of often violent extremists to the demonstrations. As documented by the Southern Poverty Law Center, an American NGO, neo-fascist groups in Britain, Europe and the US have embraced the anti-globalization credo with enthusiasm, as have anarchists and other extreme left groups. The Centre underlines, of course, that “left and right did not exactly march arm in arm” in Seattle; nor did the neo-nazi skinheads join hands with the development NGO’s in Prague. Yet the probably inevitable tendency for all demonstrations to attract extremists—a free ride is hard to decline—is certainly generating concern within the NGO community. And, indeed, in Prague, some prominent NGO’s, such as Friends of the Earth and Jubilee 2000, not only publicly condemned the street violence but refused to join the demonstrations.

But the violence of some demonstrators is not the only issue of concern to mainstream NGO’s. One of the most insistent criticisms of the NGO’s, both from member countries of intergovernmental organizations and from policy analysts, is that they misuse and distort information—either because of ignorance (some may be “global village idiots”) or in a deliberate attempt to manipulate public opinion, usually with the aid of a media that is always in search of a vivid sound bite. The most notorious example, which is frequently cited, is the Brent Spar episode, in which Greenpeace overestimated by a factor of 37 the amount of hydrocarbons that might leak from the oil rig of that name into the ocean, but certainly there are many others. It is often noted that the NGO demand for more transparency in the WTO sits uneasily with their own lack of openness in their own operations. But an interesting new development in the NGO community underlines the concern of many that their main asset, public trust, is being eroded not only by the violence at demonstrations, but, even more importantly, because they lack accountability. Of course, other actors distort and manipulate information, too, or are economical with the truth. But if corporations that engage in serious distortion are exposed (which is increasingly likely in the new information environment), they are accountable to shareholders. Governments, at least in democracies, are accountable to citizens and unions to members. But NGO’s are, in the words of one acute analyst, the “new global potentates” (see Peter J. Spiro in the Cardozo Law Review, Dec. 1996). In response to these criticisms, some NGO’s have launched new self-regulatory initiatives to develop codes of conduct. These would cover ethical practice, transparency, funding accountability, accuracy of information and other factors. Some governments are also taking the initiative in this effort. The Foreign Policy Centre (a British government think tank) has proposed a code of conduct that would include regulatory certification.

The NGO community is hardly united in endorsing codes of conduct, however, and many within it deny vehemently that accountability is an issue. Other divisions are also apparent as some NGO’s are actively engaged in cooperation with MNE’s in creating environmental and labour standards codes. NGO critics of this activity (and of cooperation with governments and donors in development projects) regard it as sleeping with the enemy. Whether these divisions within the NGO movement will fragment the mobilization networks over time is difficult to predict. Demonstration fatigue (whether on the street or for TV viewers) should also be factored into the equation. Moreover, since Seattle, police and security forces are much better prepared and some have set up special units to monitor the Internet.

But, in any case, as I have argued, the invisible impact of these new actors is probably more important than the service products of dissent.com. Thus a more significant division which could undermine the environmental movement is the wide difference between the Northern and Southern NGO’s. This divide increased in Seattle as developing country NGO’s and governments watched the Turtle-Teamster coalition marching in the streets.

As noted earlier, the most powerful transnational ENGO’s are Northern and for many in the South they reflect the political and economic power of the West—which is termed by some as “green imperialism.” Slogans aside, however, the Southern NGO’s are more concerned with development and regard the priorities of Northern NGO’s as a reflection of their high standard of living and lack of understanding of the poverty of the developing countries. In the corridors of the WTO and environmental conferences one often hears muttered complaints that “they” (the Northern ENGO’s) prefer support for elephants over people and for dolphins over children.

Southern governments, endorsed by their NGO’s, vigorously opposed the formation of the Committee on Trade and the Environment at the conclusion of the Uruguay Round. And thus far, the discourse in that Committee has been described as a dialogue of the deaf. The Southern governments regard any effort to deal with environmental issues in the WTO—despite the fact that they are already in the WTO rules—as a stalking horse for “green protectionism.” Southern NGO’s, despite efforts by Northern ENGO’s to establish North-South networks, tend to support their own governments, not only in the WTO but also at MEA conferences. It should be stressed again, however, that we don’t know who funds these Southern NGO’s or for whom they speak, so it is difficult to assess the implications of their pro-government stance on the international front. Some experts in the study of NGO’s and global governance have suggested that it is simplistic to apply an industrialized country model of civil society to developing countries. Southern NGO’s may have a much more ambivalent attitude to governments given their concern about financial resources and their support for local organizations, often against the wishes of their governments. For these and, of course, other substantive reasons they are happy to support their governments against Northern interests and power. The Southern NGO’s have also supported their governments’ opposition to amicus briefs and, more generally, to greater participation of NGO’s in WTO proceedings.

Strangely, however, Southern NGO’s are at one with their Northern colleagues in their attack on genetically modified organisms, even though the new biotechnology revolution could hold great promise for poorer countries faced with rising populations and diminishing land and water resources. Two reasons offered for their opposition to biotechnology in agriculture are a real fear of competition from big agribusiness bio-engineered crops that would wipe out indigenous agriculture and a desire to continue the ideological battle against Northern corporate oligopolies and eco-imperialism. But whatever the reason for it, this unification on a key issue for the WTO, cuts across the environment, agriculture and TRIPS, and should be explored in depth if the institution is not to be severely crippled by a hardening of the North/ South conflict left over from the Uruguay Round. Unfortunately, the WTO has no venue for this task.

Finally, as suggested by the Seattle slogan “fix it or nix it”, a movement bound by agreement on what it is against—corporate globalization—is likely to be characterized by stark differences between the “reformers” (fixers) and the “abolitionists” (nixers). The nixers’ focus is not to reform the multilateral agencies but to “deepen the crisis of legitimacy of the whole system.” But what is to replace it? The new paradigm seems to be localization. The mantra of localization and participatory democracy now appears with increasing frequency in the Internet dialogue among the NGO’s and in discussions with students since Seattle. Localization: A Global Manifesto, by Colin Hines of the International Forum on Globalization, a San Francisco-based NGO, is being widely circulated. Many deep ecologists, who have been proponents of similar ideas are strong supporters of the thesis that international trade should be cut back to supply only what cannot be produced within the local or regional economy, The book spells out the details and dimensions of the new paradigm in considerable detail and defends it with a beguiling if cumbersome slogan: “Beggar-your-neighbour globalization must give way to better-your-neighbour localization!” It will be interesting to see what impact this new approach might have on both domestic and international policies, although we may have to wait a longish time to find out.

One is reminded, when reading this and similar material, of the Owenite movement in mid19th century England. In The Great Transformation, his classic book about the 19th-century industrial revolution, Karl Polanyi describes the Owenite movement as a response to the simultaneous destruction of the crafts and of the political and social conditions which sustained local communities. Robert Owen was no Luddite but insisted that the new machines could be most productively utilized in carefully constructed communities based on consumer and worker cooperatives which established funds for unemployment and pensions as well as futuristic education schemes and other innovative projects. He denied that it was possible to separate the economy from the society. New Lanark—the first model Village of Cooperation—attracted thousands of visitors from Europe and America (and none other than Jeremy Bentham invested in some of the projects!). New Lanark and the Owenite movement disappeared, however, as capitalism began to deliver growth by the end of the century. One could say that Owen—and the new localization advocates—fit the old description of a romantic as being someone who prefers to travel hopefully rather than reach a destination. Yet it’s important to remember that long after New Lanark was forgotten some of the Owenite ideas survived in new institutions such as unions, consumer cooperatives and the beginnings of the welfare state.

The main conclusion of this paper is that the WTO is ill-equipped to deal with the challenges presented by the new global actors energized by the Internet. The WTO is a minimalist legalist institution—a Mercedes Benz without gas, as I’ve called it.

There was much talk of architecture, plumbing, interior design, and so on after the Asian financial crisis—but it was all about the Bretton Woods institutions. At Seattle, governance issues did arise but only in terms of negotiating modalities and the role of the NGO’s. (In WTO-ese, such questions are referred to as internal and external transparency.) Since Seattle nothing much has happened on either of these issues, nor is it likely to for the foreseeable future. As one insider said on the first anniversary of Seattle, “the institution is still staggering around in a daze like a boxer getting up off the canvas after a knockout.”

This is hardly the place for a full exploration of the need for reform of the WTO (which I have dealt with at length in “Making sense of it all: A post-mortem on the meaning of Seattle,” in Roger B. Porter and Pierre Sauvé, eds, Seattle, WTO and the Future of the Multilateral Trading System Cambridge, Mass.: John F. Kennedy School of Government, 2000). But in the present context, the lack of a policy forum for debating key issues is the most serious institutional defect.

Strangely enough, the GATT did have a policy forum: the Consultative Group of Eighteen (CG18) established in 1975 as a result of a recommendation of the Committee of Twenty Finance Ministers after the breakdown of Bretton Woods. It was originally termed the GATT Management Group, but its name was changed to indicate that its purpose was not in any way to challenge the authority of the GATT Council but to provide a forum for senior officials to discuss policy issues. Membership was based on a combination of economic weight and regional representation but there was also provision for other countries to attend as alternates and observers or by invitation. Each meeting was followed by a comprehensive report to the GATT Council. In 1979 the Council agreed to make CG18 permanent, but it was suspended in 1990 by the Director General (for reasons that have never been made public) and it has never met since.

Because it was a forum for senior officials from national capitals it provided an opportunity to improve coordination of policies at the home base. Papers were prepared by the secretariat on important global economic issues such as, in its early years, balance of payments and related financial matters and the nature and scope of cooperation with the Fund. After the Tokyo Round the CG18 was the only forum in the GATT where agriculture was discussed and, in the long lead-up to the Uruguay Round, trade in services. Indeed, the CG18 was the only forum for a full, wide-ranging, often contentious debate on the basic issues of the Round. It provided an opportunity to analyze and explain issues without a commitment to specific negotiating positions. Negotiating committees inhibit discussion because rules are at stake. The absence of rules is essential to the diffusion of knowledge, which rests on a degree of informality, flexibility and adaptability. Thus a policy forum can promote discussion of norms, principles, and concepts which may or may not underlie longer term strategies for new rules—such as trade and the environment, the relationship between the WTO and the UN institutions, the role of NGO’s, and so on.

The most difficult problem to be faced in creating a policy forum is, of course, membership. The biggest blockers will be the Southern countries. But if a formula cannot be agreed it may be necessary to make the establishment of the policy forum part of a new North-South package that would include the so-called “confidence-building” measures of zero tariffs for the products of the poorest countries; extension of implementation periods of some measures such as TRIM’s, TRIPS and customs valuation; and, most important, enhanced technical assistance and training.

While the establishment of the policy forum would be a great step forward, it is unlikely to function effectively without an increase in the WTO’s research capacity. If member governments are unwilling—as they have been up to now—to provide funding, other avenues should be explored, including private donors—after all Ted Turner donated one billion dollars to the UN! In order to keep up to date and reasonably small in size, the WTO could not possibly generate all its policy analysis in-house. Like most research bodies today, the WTO secretariat would have to establish a research network linked to other institutions such as the OECD, the Bretton Woods institutions, the International Labor Organization, the United Nations Environment Programme, private think tanks, universities and NGO’s, including environmental groups, business groups, human rights groups and international labour associations. The establishment of a research or knowledge network—“soft power”—is also important in order to enhance the ability of the WTO Director-General to play a more effective role leading and guiding the policy debate.

But in the end, of course, the establishment of a new CGn (or whatever) will require leadership on the part of member countries. So perhaps the best conclusion to this paper should be a variant of the Heisenberg uncertainty principle: We can know where we are but not where we’re going or we can know where we’re going but not where we are. But we can’t know both.

Photo: Shutterstock