Canadians are never satisfied with the performance of Parliament, but the reasons for dissatisfaction vary from time to time. It may be hard to remember now, but only a few years ago people were pre-occupied with the excesses of majority government. Jeffrey Simpson captured the mood in his 2001 book, The Friendly Dictatorship. When Paul Martin replaced Jean Chrétien as Liberal leader and prime minister, observers expected Martin’s “juggernaut,” as Susan Delacourt called it, to sweep to an unprecedented victory in the next election, further enhancing the power of the prime minister and rendering Parliament even more insignificant, even though Martin himself had pledged to redress what he termed the “democratic deficit.”

Stephen Harper, however, solved that set of problems when he became leader of the Canadian Alliance, merged it with the Progressive Conservatives and, against all previous predictions, reduced the Liberals to a minority government in 2004 before winning the 2006 election and forming his own minority government. Now everyone is concerned about the parliamentary problems of minority government. Who says there is no progress?

Indeed, the parliamentary problems of minority government are both real and serious. The Conservative government continues to bring in legislation but often can’t move it forward in normal fashion through committee discussion and votes on the floor of the House. Instead of just marshalling a voting majority, it has to resort to all sorts of tactical expedients: threatening to call an election, bundling other measures together with the budget, playing the opposition parties off against each other or luring dissident elements within opposition parties to defy their own leadership.

Meanwhile the opposition parties play their own games. The Liberals oppose almost everything, even measures they had previously supported when in power. Or they support bills in the House while trying to block them in the Senate. Opposition parties collaborate to pass private members’ bills that they know will be ignored because they infringe upon the government’s executive prerogatives; and they turn parliamentary committees into kangaroo courts, recklessly pursuing personal investigations for which they have neither training nor resources.

For a political scientist, it’s fascinating to watch. The last six years of parliamentary proceedings have been more entertaining than anything since the fall of Joe Clark’s government in 1979. But citizens are turned off, and rightly so, by the endless tactical manœuvres, threats, bluffs and broken deals.

Three avenues of change might arguably make things better: coalition government, institutional reform and power-sharing through a change in political culture. Let us examine each in turn.

The 2010 coalition between the Conservatives and the Liberal Democrats in the United Kingdom has touched off another round of speculation about coalition government in Canada. A majority coalition does, indeed, seem to offer a way out of our present impasse. But the facts on the ground are not conducive to coalition formation in Canada.

The first obstacle is the Bloc Québécois. As part of the separatist movement, it is an anti-system party, like the Communist parties of Cold War Europe or the neo-fascist parties of the present, and thus not an acceptable coalition partner for either the Conservatives or the Liberals. Yet as long as the Bloc controls 40 or 50 seats in Quebec, it is very difficult for either of the big parties to win a majority government. There just aren’t enough seats to go around.

That leaves three coalition possibilities: Conservative-Liberal, Conservative-NDP and Liberal-NDP. The first can be dismissed because both the Conservatives and the Liberals see themselves as governing parties. In that sense, they are implacable rivals, even if their ideologies are not that far apart. The prospect of a Conservative-Liberal cabinet makes the famous image of two scorpions in a bottle look like a happy marriage. Don’t expect a blue-red coalition any time soon.

In more abstract terms, a Conservative-Liberal grand coalition would violate the game-theoretic principle of “minimum winning coalition.” The purpose of a coalition is to gain benefits for the included winners at the expense of the excluded losers; and the larger the coalition, the more hands are extended for a share of the spoils. In practice, parties rarely form grand coalitions unless there is a threat to the system from war or revolution.

A Conservative-NDP coalition is also unlikely because it violates the principle of “minimum connected winning coalition.” Coalitions require expensive negotiations to achieve necessary compromises, and the cost increases proportionally to the distance between the partners. The Conservatives and NDP agree occasionally on specific pieces of legislation, but in general their positions are so far apart that maintaining a coalition would be extraordinarily costly. Don’t look for a blue-orange coalition soon or, indeed, ever.

In contrast, the red-orange, Liberal-NDP coalition is quite feasible. The two parties are relatively close on many issues, and only the Liberals have realistic expectations of achieving government on their own. To be in a coalition with the Liberals would be a historic step forward for the NDP, which it would take with little hesitation. Indeed, the New Democrats have already propped up two minority Liberal governments (Pierre Trudeau, 1972-74, and Paul Martin, 2004-05) without the additional benefits that can accrue from being a formal coalition partner.

The red-orange coalition could work, but can it be formed? The experience of fall 2008 shows that it would be politically risky to rely on the support of the BQ, so the Liberals and NDP together would have to control a majority of seats to make a coalition feasible. This condition is unlikely to be met as long as the Conservatives continue to win more seats than the Liberals; for in that case the NDP has to win more seats than the BQ in order to give the red-orange coalition its majority.(If C + L + N + B = 308, and if C > L, then N > B if L + N > C + B.) But the NDP has never won more seats than the BQ and seems unlikely to do so without a major collapse of the Bloc.

Of course, the current political configuration is a contingent reality, not a law of nature. It is bound to change sooner or later, perhaps in a way that will make coalition government more likely. The Liberals may once again start to win more seats than the Conservatives, or the BQ may renounce separatism and become an acceptable coalition partner as a Quebec regional party, or it may implode through a failed leadership succession after the retirement of Gilles Duceppe. But as things stand now, the one coalition that could work — Liberal-NDP — is unlikely to be feasible.

The rules regarding parliamentary structure and function have changed repeatedly during the 40-odd years that I have been observing Parliament. The length of sessions, election of the Speaker, television coverage of Question Period and debates, private members’ bills, mandate of committees and MPs’ compensation and pensions have all been addressed, some more than once. All these changes seemed like good ideas at the time, and maybe they have helped Parliament to run more smoothly; but neither individually nor collectively have they wrought major changes of the sort that are visible to voters. If they had, we wouldn’t be having this discussion.

Maybe we need stronger medicine, truly major reforms such as fixed election dates, proportional representation or an elected Senate. But wait: we already have fixed election dates, courtesy of a bill introduced by the present government and supported by all parties, and it didn’t change a thing. Given the role of the governor general in the Canadian Constitution, it is impossible to draft binding fixed-election-date legislation. As Harper showed in 2008, the prime minister will be able to ask for an election whenever he wants, because the fixed-election legislation specifically states that nothing in it “affects the powers of the Governor-General, including the power to dissolve Parliament.”

Proportional representation would make coalition government more frequent by further splintering our parties and making sure none of them could ever come close to a majority again (more or less what happened in New Zealand after that country went proportional). But don’t hold your breath. The movement for electoral reform has now failed in several provinces, including by referendum in British Columbia and Ontario. And it is not in the interest of either the Conservatives or the Liberals, both of whom have formed governments by winning as little as 36 percent of the vote. Even though there won’t be a blue-red coalition to run the country, a blue-red alliance would emerge to block proportional representation.

An elected Senate would change our system of government in profound but rather unpredictable ways. It would contain representatives of all parties, not just Liberals and Conservatives; and it would probably be rare to see majority control by any party. The government would have to negotiate multipartisan support for all legislation to get it through the Senate, which might over time make parties more amenable to compromise in the House of Commons. It is at least conceivable that an elected Senate could reduce the temperature of the partisan warfare in the House that is driving everyone crazy.

The 2010 coalition between the Conservatives and the Liberal Democrats in the United Kingdom has touched off another round of speculation about coalition government in Canada. A majority coalition does, indeed, seem to offer a way out of our present impasse. But the facts on the ground are not conducive to coalition formation in Canada.

But, again, don’t hold your breath. Even after four years of trying, the government has not been able to pass term limits for senators, let alone election as a means of selection. And even if election can be passed in Parliament, there lurks the spectre of opposition by the provinces and challenges in the courts.

The longer I observe institutional reforms to political machinery, the more I realize how inconsequential they are. Federal versus unitary, parliamentary versus presidential, first-past-the-post versus proportional representation — none of these make any real difference in the big picture. Nations that are prosperous, peaceful and well-governed have certain fundamentals in common: a spirit of constitutionalism (not necessarily a written constitution), respect for the rule of law, an impartial judiciary, representative government with periodic elections, a widely distributed franchise, private property rights and a market economy.

Beyond that, almost any variation and combination of political institutions can be found to work well. The United States is presidential, France is semi-presidential, Sweden is parliamentary. Canada has first-past-the-post elections, Australia has the alternative ballot, New Zealand has the mixed-member-proportional form of proportional representation. Germany has a federal system, the United Kingdom has devolution, and the Netherlands is a unitary state. But in spite of these differences, people all over the world are lining up to get into these countries because they are all, by world standards, wonderful places to live. Why? Not because of their political machinery, which is different in each case, but because they share the fundamentals described above.

Power-sharing is a central feature of liberal democracy. Government without power-sharing would be autocracy, literally “rule by (one) self.” Power-sharing implies not only the right of criticism and the legitimacy of opposition, but also multilateral participation in making governmental decisions. Power-sharing can be sequential, meaning that factions take turns in wielding the power of the state; or it can be simultaneous, with multiple factions cooperating to govern. In practice, liberal democracies show aspects of both forms of powersharing, but they may differ in emphasis. The British tradition of majority governments based on first-past-the-post electoral elections features sequential alternation of parties in power, whereas the consociational tradition most highly developed in countries such as Switzerland and the Netherlands exemplifies simultaneous power-sharing through recurring coalition governments based on proportional methods of election.

The main line of tradition in Canadian politics, embracing almost 90 percent of the years since Confederation, has been rule by majority government. The durability of this tradition has created a parliamentary culture of sequential powersharing based on the alternation of Liberals and Conservatives in office. Relatively short and infrequent periods of minority government have not been enough to produce a different culture based on simultaneous power-sharing. Both government and opposition parties have seen minority governments as aberrations, exceptional periods in which the strategic challenge was to elect a new majority government in the next election. And indeed, that usually happened, except for the periods 1962-68 and 2004 to the present, both of which have seen a succession of three minorities in a row.

However, it seems that the present period of minority government may go on much longer. As long as the Bloc Québécois dominates Quebec, it is extremely difficult for either the Conservatives or the Liberals to win a majority of seats, unless one or the other collapses even beyond what happened to the Liberals in 2008 under Stéphane Dion.

We thus have a mismatch between our historically rooted majoritarian political culture and a period of minority government that threatens to become a long-term reality rather than a short-term aberration. This mismatch, I contend, is at the root of Parliament’s perceived difficulties. The parties are still thinking of power-sharing in sequential terms, whereas the objective configuration calls for simultaneous power-sharing.

Nevertheless, in spite of the obvious mismatch, we saw two good examples of simultaneous power-sharing in spring 2010, when all parties supported an amended version of Immigration Minister Jason Kenney’s refugee reforms, and three parties agreed to a process for scrutinizing Afghan detainee documents while protecting national security. Neither outcome came easily. The Liberals broke an earlier agreement with the government on refugees, and the parties had to be guided by Speaker Peter Milliken to get together on Afghanistan documents. But they finally did get to the right conclusion.

Lest we become too optimistic, the Conservative government followed these power-sharing successes with an egregious example of unilateral dictation, when it decided without consultation, except under the curtain of cabinet confidentiality, to change the way the Canadian census is conducted. There was no precedent for this step in the policy manual or campaign platforms of the Conservative Party or any of its predecessor parties (Reform, Canadian Alliance, Progressive Conservatives). There was no public consultation with users of census data, and not even with the government-appointed National Statistics Council. All opposition parties were vocally opposed to the changes but will probably not unite to bring down the government over the issue, fearing an election, or at least an election over an issue that most voters will find remote and abstract.

This sort of secretive, unilateral decision-making is exactly the wrong approach to running a productive minority government. Facing a weak opposition, the government may get its way on this one issue, but it poisons the well for future cooperation on other issues. The better path is the one the government took shortly afterwards when Treasury Board Secretary Stockwell Day announced a review of employment equity in the federal public service. The opposition parties will, no doubt, oppose rescinding or relaxing employment equity measures; but at least they, along with other interested organizations, can have their say. Who knows? They may even come up with amendments that the government can accept, as happened in the refugee-determination case, thus making the outcome more broadly acceptable.

Prime Minister Harper can be a fierce partisan, but he also has substantial diplomatic skills, which he exhibited in healing the wounds in the Canadian Alliance, bringing about a merger with the Progressive Conservatives and, most recently, leading the G8 and G20 to support reductions in deficit spending. It would make a big difference if Harper would promote power-sharing by turning his diplomatic talents inward toward Parliament.

Prime Minister Harper can be a fierce partisan, but he also has substantial diplomatic skills, which he exhibited in healing the wounds in the Canadian Alliance, bringing about a merger with the Progressive Conservatives and, most recently, leading the G8 and G20 to support reductions in deficit spending. It would make a big difference if Harper would promote powersharing by turning his diplomatic talents inward toward Parliament.

But there also has to be a response from the other side. The other parties, particularly the Liberals as the Official Opposition, have to realize that they have a constructive role to play in Parliament beyond manœuvring to get back in power. In a minority Parliament they are, in effect, part of the government because no legislation can pass without their support, and with power comes responsibility.

What would power-sharing look like? Fewer “bolt from the blue” announcements of new government policies. More quiet meetings among leaders or their delegates. Government invitations to opposition parties to contribute to drafting legislation. Amendments moved in good faith, not just to obstruct. Honourable compromises. Agreements that are actually kept. Legislation that is widely supported. Not utopia, but better than what we see now.

In moving away from sequential and toward simultaneous powersharing, Canadian politicians would be following a worldwide trend. The United Kingdom, Germany, Italy and most other European countries are now governed by coalitions. The French government is not a coalition because President Nicolas Sarkozy’s UMP is a recent merger of previously distinct parties, but the UMP does not have a majority in the upper house. Government in the United States almost always involves power-sharing between Democrats and Republicans. It is unusual for one party to control the presidency Senate and House of Representatives simultaneously, as happened after the 2008 election of Barack Obama; and things may well revert to normal in the 2010 interim elections. In the Pacific region, New Zealand has coalition government, the Japanese governing party has just lost control of the upper house, and in Australia the government almost always has to deal with a Senate where it does not wield a majority.

There are many forms of simultaneous powersharing, of which coalition government is only one, and coalition government does not seem to be a likely prospect for Canada at this time. Nonetheless, cultural changes in Parliament can produce a Canadian version of simultaneous power-sharing. No institutional reforms are required. It just means recognizing that minority government may be with us for a long time and acting appropriately.

Of course, things don’t happen in politics just because they are in the public interest; there have to be electoral incentives for politicians to change their behaviour. I believe these incentives could arise if the next election confirms the minority status quo. After four straight elections yielding a minority government, it may dawn on our politicians that their majoritarian tactics aren’t working any longer, and that it can be in their own electoral interest to behave more cooperatively. At least one can hope. As a conservative, I am never optimistic, but I am always hopeful.

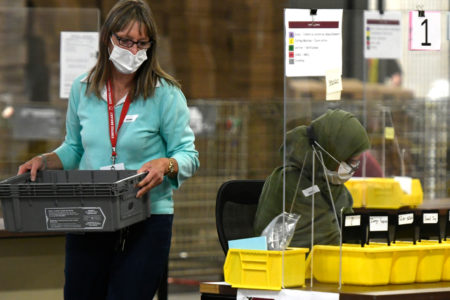

Photo: Shutterstock