“Productivity isn’t everything,” Paul Krugman once wrote in his New York Times column, “but in the long run it is almost everything.” Strange then, with Canada’s poor productivity and innovation performance compared to that of the US, that it is the United States, not Canada, that is sounding the alarm on the need to dramatically improve productivity growth and innovation. In his 2011 State of the Union Address, President Barack Obama stated: “The first step in winning the future is encouraging American innovation.”

Why are we so complacent on such a pressing issue? Where is our sense of urgency, our collective understanding of the consequences for our future competitiveness and living standards of sustained underperformance in productivity and innovation? Why are we not engaged in a national search for solutions? Clearly, there is a need to change course on the well-trodden analytic path examining Canada’s pervasive productivity slowdown and how the consequences of the problem are communicated.

Our traditional analysis has focused on the “contributions” of labour and capital to productivity, with a catch-all residual that includes all the other factors that influence productivity. While this approach has identified the severity of the productivity slowdown, its limits in identifying possible solutions are reached when the “residual” begins to dominate the analysis, highlighting our ignorance rather than our understanding of Canada’s poor productivity performance. We believe it is necessary to combine this with a “micro,” or corporate choice, approach, one that attempts to better align productivity and innovation analysis with the way a firm conceptually approaches strategic business decisions.

A typical firm does its planning in the context of its products, its markets, its organizational structure and its production process. The firm does so in a world that is constantly changing and evolving, and in uncertain ways. Unless the firm understands this, and incorporates it formally or informally into its planning processes, the firm’s future prospects will be diminished. Innovation can be thought of as the process by which successful firms understand this dynamic, change, adapt and modify their products, processes or concepts of markets to take advantage of the changing environment. Those who do so well prosper. Those who do not, fall behind.

An American productivity expert, Dale Jorgenson, has observed: “Productivity growth is the key economic indicator of innovation.” We agree, and would argue further that to understand productivity is to understand innovation. Put differently, productivity growth is the dividend produced by innovation. It magnifies the value of the output produced by the firm’s labour and capital inputs.

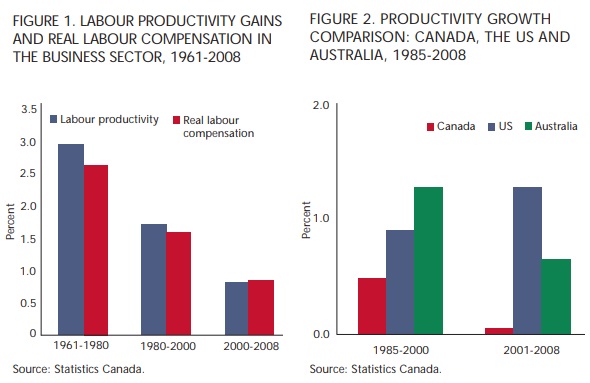

First, productivity growth in Canada has dropped substantially and continually over time, from average growth of close to 3 percent annually from 1961 to 1980, to under 1 percent annual productivity growth since 2000. Second, underscoring the crucial point that productivity growth drives real wages, the growth in Canadian labour compensation has dropped substantially and commensurately over these same periods.

The facts of Canada’s poor productivity performance are well documented but worthwhile summarizing again briefly. Figure 1 provides a perspective not only on the growth in labour productivity over three time periods since 1960, but also on how labour income growth has progressed over the same periods.

Two observations can be quickly made from these data. First, productivity growth in Canada has dropped substantially and continually over time, from average growth of close to 3 percent annually from 1961 to 1980, to under 1 percent annual productivity growth since 2000. Second, underscoring the crucial point that productivity growth drives real wages, the growth in Canadian labour compensation has dropped substantially and commensurately over these same periods. This highlights the crucial point that productivity growth is as much a social issue as an economic one because it defines our aggregate living standards.

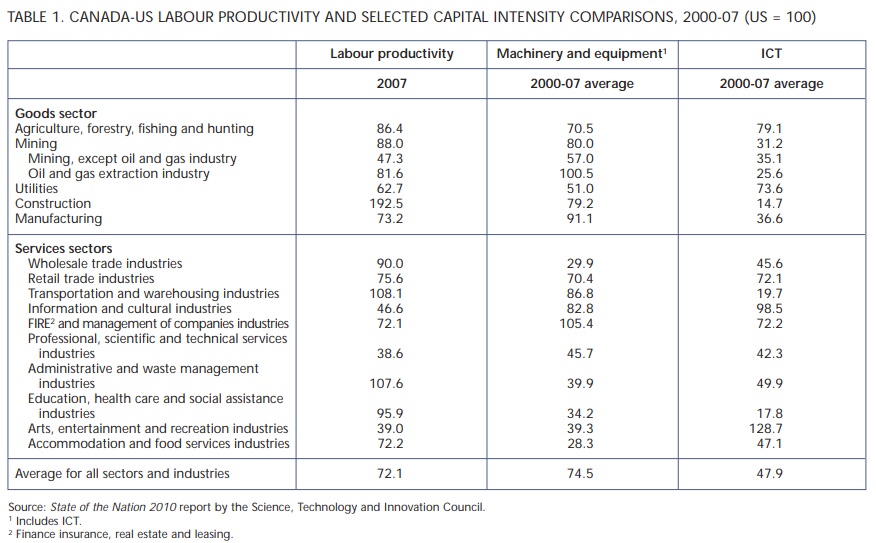

Contrary to a commonly cited myth, the scale, scope and duration of this deterioration in Canadian productivity performance are not part of a worldwide phenomenon; they appear to be made in Canada. Figure 2 compares productivity growth in three countries: Canada; the US, our largest trading partner; and Australia, a country more similar to us than many others in terms of economic size and the structure of the economy. In both the 1985-2000 and 2000-08 periods, for which comparable data are available, Canada underperformed the other countries, and by a considerable margin. Moreover, the gap widened between Canadian and US productivity growth over the last decade rather than showing any convergence as might be expected by the relative improvement of macroeconomic fundamentals in Canada.

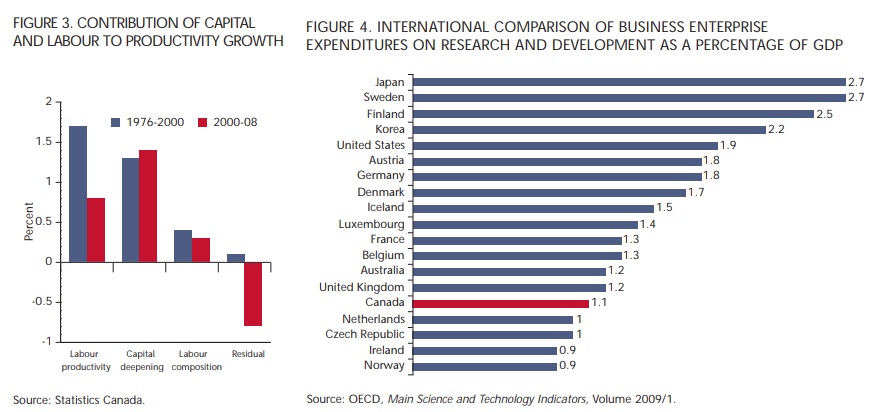

How is this economy-wide productivity performance reflected at the sectoral level and what does it mean for firms? The recent State of the Nation 2010 report by the Science, Technology and Innovation Council sheds more granular light on Canada-US differences in productivity performance, and table 1 draws from its findings. It shows that aggregate Canadian business sector labour productivity levels in 2007 were only 72.1 percent of those of US business, and these gaps were evident across a wide range of sectors. Strikingly, Canadian businesses also employed machinery and equipment, and information and communication technologies (ICT) less intensively than their US counterparts, about 25 percent less in the case of machinery and over 50 percent for ICT.

In the search for a better understanding of Canada’s poor and worsening productivity performance, figure 3 shows a breakdown of the “contributions” of capital and labour to productivity growth. What do these data show? For the post-2000 period compared to the previous 25 years, the contribution of capital deepening to productivity growth has risen, while that of labour composition has diminished somewhat. The surprising message from the figure, however, is that the residual — that part of productivity performance that is not captured by the tangible factors of capital and labour — has become large and substantially negative. This residual, normally called multifactor productivity growth, is a testament more to what we do not understand than to our knowledge.

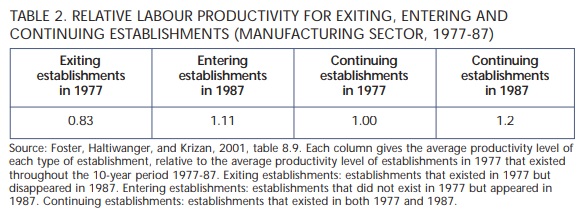

Despite one of the most generous tax regimes in the world for research and development, Canadian firms ranked 15th among OECD countries in R&D spending as a percentage of GDP.

This less than attractive productivity performance has happened despite the expectation over 20 years that Canada’s performance in this area would improve thanks to many policy reforms undertaken over this period, of both a structural and macro nature.

What about innovation performance? Canadian indirect measures for innovation such as business spending on R&D and patents are not encouraging. Despite one of the most generous tax regimes in the world for research and development, Canadian firms ranked 15th among OECD countries in R&D spending as a percentage of GDP. As figure 4 starkly shows, Canadian business spending on R&D is only 1 percent of GDP, well below the OECD average of 1.6 percent of GDP, half that of the US and one third that of countries like Sweden, Netherlands and Korea. The World Economic Forum Global Competitive Index rates Canada as underperforming its overall ranking in technological readiness, innovation and business sophistication.

How have policy changes affected recent Canadian productivity and innovation performance? In the mid-1990s, part of the conventional business explanation for productivity underperformance was the extensive imbalances in Canadian public finances, high corporate tax rates, high interest rates and unfunded public pensions.

But, as noted above, Canadian productivity growth declined again over the last decade despite an impressive list of policy reforms including elimination of chronic budget deficits; large decline in the public debt-to-GDP ratio; tax system reforms; some integration of federal and provincial sales tax systems; employment insurance reforms; price stability; large declines in corporate income tax rates to below US levels; and the CPP-QPP pension system being put on a sound footing. One possible explanation is the need to look more intensively into the factors that motivate or constrain a firm’s innovation and productivity strategy.

Consider the stylized case of a Canadian firm, sheltered from strong competitive forces, unaccustomed to global markets, producing a stable product mix, led by a management team with limited high-tech experience and reticent to invest in “soft assets” such as research and development, customer feedback systems and marketing. Would any of the macro and tax policy reforms described above significantly incent this firm to invest more in innovation and in productivity? Unlikely.

Would our stylized firm have done less well without these reforms? Unambiguously not. Will this firm be well positioned for growth and sustainability in a rapidly changing world, with shifting markets, tastes and technologies? Not at all. For this stylized firm, the basket of wide-ranging macro and tax reforms were necessary but not sufficient conditions for a more productive, innovative corporate behaviour.

To reinforce the importance of corporate strategic choices for economy-wide outcomes, recent analysis by Chad Syverson (2010) examines differences in productivity distributions across firms within similar business sectors. The analysis is quite striking: “The plant at the 90th percentile of the productivity distribution makes almost twice as much output with the same measured inputs as the 10th percentile plant.” From this analysis he concludes that, “put simply, some producers seem to have figured out their business (or at least are on their way), while others are woefully lacking.”

And the same basic point emerges from a 2001 study by Foster, Haltiwanger and Krizan (table 2), who examined the productivity performance of four categories of US firms: those that exited in 1977; those that entered in 1987; those that continued in 1977; and those 1977 firms that continued in 1987. Firms that failed in 1977 had a productivity level 17 percent less than that of continuing firms; firms that entered the economy in 1987 had a productivity level 11 percent higher than the 1977 average of continuing firms; and 1977 firms that survived to 1987 were more productive than the 1987 new entrants by a significant 9 percent and a whopping 37 percent more productive than the exiting firms of just a decade earlier.

Both studies point to the fact that firm-level decisions about innovation and productivity really matter both for long-term firm survival and for economy-wide macro outcomes. They support taking a more micro approach to the drivers of productivity growth, including how firms organize for innovation and productivity performance.

A broad and timely perspective on Canada’s innovation and productivity performance comes from the State of the Nation 2010 report. In evaluating how we are doing as a country in building the “infrastructure” for innovation, the report notes that “current best efforts are not getting us to where we want to be.” It concludes: “An excellent talent pool and increased efforts by government, higher education and some industries are not preventing stagnation in Canada’s overall innovation performance.”

Conventional economic analysis of productivity performance looks at it in terms of a standard production function, where output is assumed to be largely determined by the labour and physical capital inputs. The contribution of all other factors is captured through a residual term, normally referred to as multifactor productivity. What factors shape this residual or multifactor productivity is much less well understood.

The challenge with multifactor productivity as an explanatory framework is that no firms sit down and establish a multifactor productivity strategy; they have no idea what it is. Rather, a typical business thinks about the markets it wants to serve and the relevance of its products for potential customers in these markets. It has to decide how to organize itself and establish a decision-making structure to ensure it does it well. It has to hire, train and compensate workers, and decide what kind of human resource management policies it needs to do this effectively. It has to choose the best possible production processes to produce its goods and services and the means to get them to its markets. It has to decide whether to fine-tune or change its products depending on what competitors are doing and how tastes are shifting. It has to decide whether to modify the markets it wants to serve, and how to market and brand its products in these markets.

Simply put, the conventional productivity approach is consistent with how a firm thinks about the amount of labour and capital it needs to operate, but sheds little light on the residual or multifactor productivity.

The world around this typical firm is not static; it is constantly evolving. Consumer tastes are changing. Technology is changing. Markets are changing. In today’s era of rapid change, a firm has to make decisions about how to cope with this dynamic environment amid much uncertainty. The challenge is how and how well firms react to this environment of constant change. This is where innovation enters the picture.

Innovation is the essence of how a dynamically successful firm “stays ahead of the curve.”

In our view, part of the “how” requires continual business innovation in four distinct corporate areas: organizational innovation, product innovation, market innovation, and process innovation.

- Organizational innovation: The strategic capacity to convert creativity, market and customer knowledge and technology into marketable innovations requires a corporate focus on how to best organize and manage for innovation. Vijay Govindarajan and Chris Trimble in their 2010 book, The Other Side of Innovation: Solving the Executive Challenge, argue that innovation is anything but inherent in large corporations. Rather, the managerial tendency is to cluster around the status quo, emphasizing incremental improvements, rather than actively managing to upset the status quo, which is the essence of innovation. They believe successful corporate innovation requires planning and implementation structures that accommodate dedicated innovation teams, working separately to develop a new innovation and hard-wired into the corporation through a “shared team.” It requires management to fight the tyranny of short-termism, and integrate human capital management, technology management and strategic management in structures that are “innovation supportive.”

- Product innovation: The strategic and technological capacity of a firm to introduce new products and new services ahead of competitors, to anticipate consumer wants and needs or even to create them. New products that move up the value-added chain or are the first to market typically carry higher profit margins and face less cost competition than standardized products. Such product innovation can be the result of research and development, or the result of aggregating existing leading technologies in a new way that better meets consumer demands. Product innovation occurs best when it is at the intersection of a sophisticated understanding of consumers and of technology. As Andrew Bernard, Stephen Redding and Peter Schott, writing in American Economic Review, have shown for the US, start-ups disproportionally bring product innovations to markets.

- Market innovation: The strategic capacity of a firm to decide to change its market, whether geographically (e.g., entering the US after the FTA, or China, India or Brazil today) or virtually (e.g., using the Internet to extend reach) or creatively (e.g., creating a new market by convincing consumers that they want or need something for which there was no previous market), and to implement such a market pivot. This shifts a firm from fighting for market share in existing markets to a temporary “monopoly” position for its particular product in the new market, increasing its scale and pricing potential. Market expansion with stable products in mature markets is close to a zero-sum game.

- Process innovation: The strategic capacity to change how goods and services are produced and delivered to reduce cost, improve efficiency and increase convenience for customers. Developing global supply chains and risk-sharing partners in manufacturing are prime examples. Internet-based shopping and banking are two service sector examples. Value-based or frugal innovation, for which India is increasingly well-known, engineers backwards to achieve the best product for a fixed price point that achieves the firm’s market scale objectives. More generally, it is the capacity of a firm to reimagine what its core competencies are, and are not, in the production and distribution aspects of its business, and alter the status quo accordingly.

What do we know about these four areas of corporate innovation? Are they mutually exclusive or do they interact synergistically? Probably, different firms should require or employ different “innovation mixes,” given their circumstances and opportunities. But the more firms innovate in all four of these areas, the more successful they should be in their productivity performance.

A 2009 Netherlands study by Richard Polder, George van Leeuwen, Pierre Mohnen and Raymond Wladimir examines this very point. It measures the impacts of factors generally associated with innovation, such as R&D, the use of ICT, the introduction of new goods and services (i.e., product innovation), novelties in methods of production (process innovation) and management and marketing (organizational innovation). They find that R&D has its main effect in generating product innovation in the manufacturing sector, and ICT particularly impacts innovation in the services sector. They also found that ICT has a marginal product that is eight times larger than equal-value non-ICT capital when combined with organizational innovation. From the perspective of the impact of the four corporate innovation areas discussed above, they found that process, product and organization innovation, particularly when combined, significantly impacted both the manufacturing and service sectors and were particularly impactful in services.

A study by IBM also demonstrates how a company’s innovation mix can vary from that of its peers. IBM conducted an extensive global survey in 2006 to better understand what drives innovation in the electronics industry. It interacted with 765 CEOs and business leaders in major companies across many countries to understand the importance of innovation to these corporate leaders and how they “managed” innovation within their firms. In particular, the study was designed to get their views on how much organizational, product, market and process innovation mattered to them and their firms. For the study, innovation was defined broadly as “new ideas or current thinking applied in fundamentally different ways resulting in significant change.”

Organizational innovation was the priority for about 25 percent of the firms; product and market innovation (combined in the IBM study) was the focus for 45 percent of the firms; while process innovation was front and centre for about 30 percent of the firms. CEOs also were asked to identify the main external factors in motivating firms to innovate, and they cited two: access to new markets (with 74 percent identifying India and China as these markets) and changing technology (identified by 70 percent of the firms).

Does organizational innovation improve corporate performance? An important question, and one that Fardad Zand, Cees van Beers and George van Leeuwen have directly examined in a 2011 paper by Statistics Netherlands. They asked the following question: Why do some firms benefit from investment in ICT while others do not? They conclude that ICT and organizational innovation are complementary. In other words, the productivity effect of ICT significantly increases when technology investments are accompanied by relevant organizational changes. Simply put, applying new technology to old processes constrains the productivity potential of the technology rather than enhancing it as new processes can.

With process innovation, does the structure of the workplace matter? Sandra Black and Lisa Lynch in papers in 1999 and 2005 tackled this by examining the relationship between innovation, productivity and wages. They found that firms that re-engineer their workplaces and incorporate high-performance practices experience higher productivity. Innovative workplace practices appeared to explain close to 90 percent of the movement in multifactor productivity over the period of their 1999 US study.

The importance of market innovation is touched on in a 2010 Canadian study by John Baldwin and Beiling Yan, which looked at the impact of opening up export markets for the productivity of Canadian firms. They examined the experience of Canadian manufacturing plants over periods that featured different rates of bilateral tariff reductions and different bilateral real exchange rates. Canadian companies tend to self-select into export markets — that is, more efficient plants are more likely to enter and less likely to avoid export markets. Further, entrants to export markets improve their productivity performance relative to the population from which they originated. These results certainly support the perspective that operating in new markets boosts productivity.

The IBM study also delved into who was driving innovation in the firms surveyed. Perhaps tellingly, CEOs personally took charge in 35 percent of the firms; senior and clearly designated executives were in the lead in about 40 percent of the firms; and in the remaining firms, responsibility for driving innovation was not clearly articulated. Unfortunately, there are no data to see which innovation leadership model was the more successful.

But there is research on the importance of management to corporate productivity. Surveying mediumsized manufacturing firms in 17 countries on 18 specific management practices, Nicholas Bloom and John Van Reenen in a 2010 study for the Journal of Economic Perspectives found that measures of better management practice were strongly associated with superior firm productivity. They also found significant variation in the quality of management across countries, with US firms best managed, followed by those in Germany, Sweden, Japan and Canada, which ranked fifth (with a large gap between Canadian and American firms). They also found surprising variation among firms within each country.

To conclude this corporate-level analysis of innovation and productivity performance, a recent study by the Economist Intelligence Unit surveyed 400 senior executives of multinational enterprises with strong track records of productivity and innovation performance. These business leaders placed a strong emphasis on the importance of strategic planning (organizational innovation) and indicated that the strategic choices with the greatest impact were introducing new products and services (product innovation), entering new markets (market innovations), using best available technology (process innovation), acquiring strategic partners with complementary know-how (process innovation) and strategically managing human capital (organizational innovation). A different perspective, indeed, on what influences multifactor productivity.

Today, we have a strong dollar and weak productivity. We have strong public research capacity in our universities and weak private sector innovation and commercialization. We have deep trade links with the US and weak linkages with the dynamic emerging economies. Canada is in an excellent position to prosper, provided we build on our strengths and tackle our weaknesses.

What have we learned from this examination of innovation and productivity, and what does it suggest as to ways to improve Canadian performance? Clearly, we need a stronger culture of innovation in our business community, with greater managerial focus on continual innovation and productivity and less risk aversion to change. There are clear limits to the effectiveness of policy support by government unless corporate management teams understand and value innovation as a key business strategy for competitiveness and growth.

More specifically, a number of possible drivers of corporate innovation have surfaced and are worth further consideration.

First, competition matters to corporate behaviour. We need to introduce a more competitive frame into the Canadian business environment, and a more international mindset into Canadian management. One possible avenue is policy changes to increase market competition in Canada. Another is more trade agreements with dynamic emerging economies. A further is to introduce more “information-driven competition” into Canadian business decision-making, with a possible vehicle being a national productivity and innovation council that would produce global best-practice benchmarks for key sectors of our economy that would be public so that both markets and boards of directors would be encouraged to take these into account in evaluating corporate performance.

Second, government support for corporate innovation in Canada is predominantly through the tax system, with one of the most generous research and development tax credits in the world. Since Canada appears to be an outlier among OECD countries in the high proportion of private sector innovation funding delivered through the tax system, and the evident ineffectiveness of this mechanism, consideration should be given to redirecting some of these innovation tax expenditures to direct support for innovation. This could include a revamped and expanded IRAP (Industrial Research Assistance Program), with a greater focus on helping firms adopt leading-edge technologies and best management practices, and a Canadian equivalent to DARPA, one of the US government’s most successful research and innovation engines. It could also include more applied research to create sectoral-based clusters of innovative excellence, in partnership between universities and the private sector, and again geared to emulating best-in-global-class performance. We should also invest in more leading-edge technology demonstration projects, focused in sectors where Canada has inherent comparative advantages.

Third, financing is crucial, both for start-up innovative firms and for established firms that wish to invest more in innovation and productivity. The venture capital industry in Canada is simply not functioning the way it should, and we seriously lag other countries as diverse as the US, Israel, Singapore and the UK in this key element of launching start-ups with innovative product or market ideas. But banking system financing for innovation and productivity investments in established firms is not what it can and should be, and this is an area of lending that banks should develop more expertise in, in both advising clients and facilitating credit.

Fourth, access to new technologies is essential for innovation and productivity. While not all firms can or should perform their R&D in-house, all firms should have senior managements that are technologically literate about today’s leading technologies and where the technology may be going tomorrow. We have excellent research universities and strong community colleges in Canada, but too little interaction between them and businesses, and vice versa. We need better mechanisms and incentives to encourage greater movement between these sectors to the benefit of both.

Fifth, management and management structures clearly matter. Are we developing managers who are experts in global marketing, who understand the core technologies for their sectors, who are comfortable in risk assessment of product innovation? Managers who are at the leading edge of customer analytics, who are creative in using the Internet and social media for market innovation, who have experience in organizational innovation? We should, because our competitors in other countries surely are. And are our education systems geared to the needs of a globally oriented, knowledge-based economy, where multiple language skills and knowledge of other countries and their markets are a necessity? Are our graduate schools emphasizing the cross-disciplinary skills and entrepreneurship necessary to succeed in a rapidly changing and uncertain world? Again, we should, because a number of other countries are ahead of us in this regard.

Most importantly, we should avoid any tendency toward national complacency. We have done well as a country, are blessed with much, and yet there is much we need to do. Today, we have a strong dollar and weak productivity. We have strong public research capacity in our universities and weak private sector innovation and commercialization. We have deep trade links with the US and weak linkages with the dynamic emerging economies. Canada is in an excellent position to prosper, provided we build on our strengths and tackle our weaknesses. Poor innovation and productivity performance are weaknesses that are in need of early tackling.

Photo: Shutterstock