The WikiLeaks release of 250,000 US diplomatic “cables” is an act essentially without precedent. Some commentators have argued that its revelations are resetting the geopolitical landscape. Others scoff that there is so far little in these messages that sophisticated analysts didn’t already know.

The truth as usual is somewhere in between, and on another level altogether. These messages written over the last few years do provide an extraordinary composite snapshot of an increasingly competitive and mendacious world. Apart from geopolitics, the cables describe smugglers, ex-military fixers and corrupt politicians and businesses. We see the US struggling, more or less vainly, and also more or less alone, to promote greater order region by region. There may not be many revelations that are startlingly new to insiders, but seeing in black and white these reports describing tactics, strategies and considerable double-dealing including by American partners may have salutary effects on behaviour.

That after all is the point of WikiLeaks, which considers itself a new form of investigative journalism aiming to bring transparency to the duplicitous antics of the troubled and competitive world. Observers disagree over the costs and benefits of the approach.

But one thing is clear, or ought to be. WikiLeaks is part of a changing communications culture that is reshaping the relationship between citizens and the state. New technologies have flattened the information world. Members of the public with access to a myriad of information snippets and critical opinion have become skeptical about public communications from the state and from corporations. They insist on transparency. Official and business institutions are scrambling to try to understand the implications and to alter behaviour to catch up.

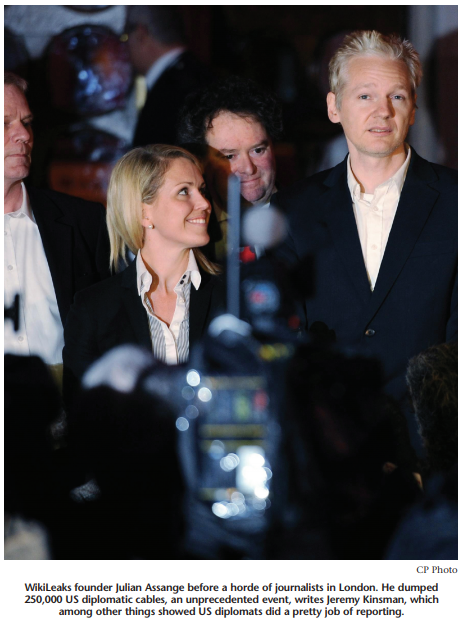

For now, US official and political circles are vividly hostile to WikiLeaks and its founder, Australian Julian Assange. It is understandable that US security agencies would view the theft and release of all these secret and often embarrassing messages as an act of vandalism perpetrated by a “dangerous anti-American gadfly” whom some have elevated into a terrorist worthy of being compared to al-Qaeda (Sarah Palin). Secretary of State Hillary Clinton has asserted the leak “puts people’s lives in danger, threatens our national security, and undermines [US] efforts to work with other countries to solve shared problems.”

This is the rationale for trying to shut WikiLeaks down, and even bring Assange before US courts. At the time of writing neither effort seems likely to succeed.

The leaked documents have spread to over 700 sites in addition to the chosen newspaper outlets to which Assange has sent the material (the New York Times, Le Monde, the Guardian, El Pais and Der Spiegel), which are releasing it bit by bit, apparently judiciously in that they are excluding some messages that are salacious without being significant.

As to Assange’s criminal liability, it is unclear what he has done that is illegal. The as yet unknown US official who has followed the example of Private Bradford Manning, who anonymously smuggled out to WikiLeaks the first wave of US messages on Afghanistan (disguised as Lady Gaga CDs), presumably is liable under official secrets provisions. But the act of accepting and publishing such leaks was judged by the Supreme Court at the time of the publication of the Pentagon Papers to be without liability. Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart underscored in his opinion at the time the public interest is always consistent with “maximum possible disclosure.”

Moreover, the WikiLeaks releases of US official reporting from around the world do not disclose official duplicity, in the sense of any effort to bilk the US public in the way the Pentagon Papers revealed had been done by the government en route to the Vietnam quagmire.

Of course, “maximum possible disclosure” has a rational limit, even for cyber-libertarians. The US has to be able to communicate in confidence in its diplomatic activity. Possibly even more important, it has to be able to protect the integrity of information received in confidence. Counterterrorism communications especially need protection, though most governments consign messages on counterterrorism to a higher tier of encryption with strict need-to-know rules regarding access.

In the first public speech ever by a serving head of the UK’s Special intelligence Service, Sir John Sawers asked, in effect, “How secret does a secret service have to be?” Sawers referred to a letter to the London Times that queried, “Is it not bizarre that MI5 and MI6…currently stand accused of being — er — secretive?” Sawers judged the reader was “on to something.” At some level of national interest, countries have to be able to protect secrets about how they gather information other people don’t want them to have.

To enable this, the US government will have to be able to provide credible assurance that it has completely redone its insane practice of sharing such confidential messages among a vast throng of officials and contractors. The co-chairman of the 9/11 Commission, Lee Hamilton, testified that “poor information sharing was the single greatest failure of our government in the lead-up to the 9/11 attacks.” But the remedy of enabling what some estimate to be millions of people to have access to the State Department’s “Net-Centric database,” created in the wake of the 9/11 disaster in order to break down the infamous information silos of the various agencies was a set-up for the WikiLeaks train wreck.

The Washington Post reported that 856,000 officials had clearance for access to top-secret material. That number will have to be thrashed down, and the inflation in classification of documents as secret will also have to be reversed. US government sources report that the number of such documents has increased tenfold since 1996.

There is increasing international belief that the US has overreacted in its hostility to the leaks and risks coming across as supporting censorship and intimidation at a time when US policy has been widely trumpeting that access to information on the Internet is an essential right and an encouragement to freer societies. Some of these overreactions look very foolish. On December 15, the US Air Force blocked access to the Web sites carrying leaked US diplomatic correspondence for employees who work on the Air Force’s communications system.

So, apart from showing that the State Department’s communications system needs an urgent remake, what else have the leaks shown? What are the costs of US diplomatic thinking and activity being revealed in this way, beyond encouraging sources and those who report on them to be more careful, and hence less useful, in what they commit to paper? Secretary of Defense Robert Gates estimated the “consequences” for US foreign policy are “fairly modest.”

Some professional relationships may be bruised. For example, the German foreign minister described by the US ambassador as “incompetent, vain, and critical of the US” may hold it against the envoy (thereby validating the description).

Speaking of vanity, President Sarkozy’s “susceptible” and “authoritarian” personality is no state secret, nor is it a revelation to read that Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi is all the clownish things we already knew. Chancellor Angela Merkel’s risk-averse and prosaic lack of creativity has been noted by many more than the authors of US diplomatic cables, including conservative Germans inclined to applaud. The “Batman-Robin” characterization of the Russian Putin-Medvedev leadership dyad was cute enough. Not so cute but very useful to get out in print is the sober analysis of the mingling of state and organized crime in Vladimir Putin’s Russia. I, for one, am glad the world knows more of the dictator of Uzbekistan, Islam Karimov, and his mobster daughter, Gulnora. That Prince Andrew is a dolt and that the Pope, in his aggressive efforts to recruit Anglicans to Roman Catholicism, comes across as a dogmatic sectarian are leaks that validate long-standing impressions.

All these people inhabit bubbles, and it ought to help them to hear how they come across to outside professionals whose opinions can’t be dismissed as those of dissidents, political opponents and journalists. Taken as an ensemble, the profiles of European leaders do give an indication of why the European Union is increasingly a weak and uncertain partner.

Of course, the writers of these cables live in something of an institutional and America-centric bubble of their own. Diplomats tend to write home in support of their government’s policies, and the cables from US diplomats in Havana whine about the reticence of non-American diplomats to mirror US megaphone diplomacy to try to change Cuba’s undemocratic ways (even though I know from experience that most US officers there regard their policies on Cuba to be bankrupt and unproductive).

Some European observers profess to see in the personality portraits of foreign leaders an “American” preoccupation with celebrities rather than issues. But the vanities, limitations, temptations and inhibitions of leaders shape our world.

Yet that truth should never have justified a message to US personnel at the UN to try to obtain personal identification data on UN Secretariat figures so as to enable better spying on them. That was embarrassing because it was so dumb. But this shows the sort of over-reach typical of power-inflated security agencies and demonstrates why they need constant parenting.

Overall, the leaked cables do convey a vivid professional preoccupation with issues great and small, and the analysis is generally astute. From attempts to curtail drug trafficking into Africa to challenges in the major theatres of conflict and competition, we read of US personnel straining in an uphill effort to obtain cooperation in the interests of peace and security from often incompetent or venal local governments.

Several observers detect not just an excellence in the reporting, but also a remarkable concordance between the public aims and private practices of US diplomacy itself. For example, these analysts and envoys actually do support democratic activists and human rights defenders, thoughtfully and deferentially. The former Canadian aid worker Scott Gilmore has written convincingly that this kind of diplomatic support work has to protect conversations and the identity of contacts, but I have not seen evidence to contradict Assange’s claim in a Financial Times interview that the leaked material has not placed any such people in harm’s way.

The upshot is that diplomacy has been validated in the public mind, not just because US diplomats seem to know what they are doing, but because the diplomatic track comes across as highly relevant.

It has enhanced the profession’s reputation. The Georgetown School of Foreign Service in Washington, DC, reports a surge in interest.

Does all this apply only to US diplomats? In every country the American ambassador is in a unique situation compared to his colleagues. On the diplomatic circuit, they envy our ability to skip the ritualistically tedious National Day receptions of marginal little countries, while we envy the reality of their power and access, and their personal authority. The power and access are self-evident, born of the influence that goes with being a superpower, however beaten around the ears the US may seem to some today. As Richard Holbrooke often said, diplomacy is always more effective when backed by credible military capability and economic reach. His untimely passing in December is a serious loss to American efforts to counter the insurgency in Afghanistan as well as to encourage Pakistan to become a more reliable ally in the region.

The greater relative authority of US ambassadors is less self-evident outside the profession. It is almost always more purposefully deployed than is the case for counterparts, and especially from Canada today. For years, the Canadian foreign service has been the object of wariness from mandarins at the “centre” of the Ottawa bureaucracy, precisely because, a la Richard Colvin, Canada’s diplomats had a habit of speaking their mind and reporting in that vein. With the central control exercised today in all areas of communication by the Prime Minister’s Office, that spirit is interpreted as disloyalty. Whereas US ambassadors, confirmed by the US Senate, are trusted to get the message out publicly in their country of accreditation, without having to check every line and nuance with Washington, Canadian envoys who need to be branding our usually invisible country are kept on a short communications leash.

Indeed, they are selected not for their communications skills nor for their analytic ability, but for their orderly and disciplined attention to business plans, ratings reports and the consuming flood of administrative requirements their headquarters and the Treasury Board concoct. In consequence, the Canadian foreign service culture has become risk-averse and bureaucratically conventional, increasingly peopled by non-foreign-service personnel who can be relied on to keep their eyes above all on the servicing duties of the bureaucracy back home rather than on geo-political developments abroad. It is an invitation, as a US ambassador to Rwanda said about the disaster there, to “turn away from the warning signs.”

If there is genuine interest in knowing why Canada is no longer internationally creative, or how Canada could have made the series of blunders it has made in the last year and more that cost us the world’s support for a UN Security Council seat, the thought process could usefully start here.

That being said, surviving pockets of excellence among Canada’s representatives will have reported on many of the topics that have been illuminated by WikiLeaks. But they wouldn’t have been able to contribute to an assessment and policy readership that would matter, and certainly not among the internationally unexposed politicians who have recently in bafflement ventured abroad as Canada’s foreign ministers.

In any event, we have at least on this occasion some pretty good US thinking on the issues and some pointed reminders:

- that China wavers between paranoia and hubris, seemingly convinced the US is trying to constrain China’s “rise,” and obsessed with political control at home to the point of orchestrating cyber-attacks on Google;

- and yet, that China is not monolithic, harbouring a probable diversity of views on how to handle North Korea and even eventually Korean unification;

- that Iran, detested in the Middle East, and possibly the possessor of North Korean missiles, creates nuclear anxiety for more than the Israelis, as the Saudi king urged the US to whack the Iranian sites earlier rather than later;

- that everyone should worry about Pakistan’s fissionable material getting into the wrong hands;

- that the Ukrainian freighter seized by Somali pirates did have Sovietera weapons bound for breakaway South Sudan;

- that multinationals like Shell, Pfizer and BAE are behaving toward Africa exactly as John Le Carré depicted, as post-colonial masters;

- that the treasure we have poured into Afghanistan has enriched the fortunes of such as former vicepresident Ahmed Zia Massoud, seen depositing $52 million in Dubai bank accounts.

But where are the patterns?

Barack Obama promised that as president he would engage with adversaries and allies alike. There is much evidence in the cables that the US is doing so. But we also see frequent reliance on Plan Bs that include the possibility of international coercion or sanctions. President Obama and Secretary Clinton are running a cerebral and not ineffective set of regional policies. As we see with respect to the “long game” over Iran, deadlines and incentives run in parallel. Some commentators regret that Iran’s leaders are able to see the US strategy. It would have been apparent to them already. What they had perhaps not noted from inside their topdown political bubble is just how encircled and weakened they seem.

Does the US come across in these cables also as weakened, as a “waning” power? These pages have carried several analyses in the last four years underlining the dispersal of power to new players, such as China, India and Brazil, an essentially positive phenomenon. The leaked cables show that the US gets the world as it now is and is attempting to network effectively.

But the reader does not have the impression that other countries are helping out much — jockeying for position seems their standard impulse. On the other hand, there isn’t much evidence that the US readily offers other players a lot of ownership on the issues. When it does, which in fairness has happened with Russia over the ABM issue, support emerges for issues at the top of the US agenda such as Iran, North Korea and nuclear proliferation.

We don’t see the full picture, of course. Really sensitive intelligence is carried on a separate tier of communications. Some editing and selection choices are being made by the newspaper outlets with which Assange has shared the material.

On follow-up, let’s assume the State Department reorganizes its systems and database access and regains the ability to maintain the integrity of communications. Let’s also assume that it sees that going after Assange is a no-brainer loser.

Apart from the photo of the geopolitical landscape the leaked material provides, what have we learned from this episode?

It confirms something that has been apparent for some time to acute observers of the information and information technologies world: that government communications practice has to change, especially in changeresistant security services, which have a long-standing culture of secrecy.

BBC journalist Nik Gowing has not let his prominence as BBC World’s star news presenter slow down his long-standing personal research into the topic, which has resulted in an analysis done for the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism at Oxford.

“Skyful of Lies” and Black Swans is being avidly consulted by officials from Delhi to Hong Kong, Brussels and Washington.

Gowing sees how real-time media is changing our world. He perceives how technology has produced a new public information space that creates a wave of democratization and accountability and that also shifts and redefines the nature of power.

Gowing was one of the first to recognize the power of “netizens” whose cellphone photo witnessing has brought into the light many events that security agencies have long been accustomed to keeping secret. The RCMP has long managed to conceal abuses of power and misjudgment in the field but the fatal tasering of Robert Dziekanski at Vancouver airport was a gamechanger, even if the throwback RCMP embarrassingly still doesn’t get it.

Gowing has also seen how the public — almost everywhere — has begun to believe that it already “knows” the general direction of activities today because of the way the Internet and other applications report on developments in real time. A recent example he gives is that during the November 10 demonstrations by students and other protesters over the UK government’s austerity measures, netizens inside the Conservative Party HQ, which was under attack and threat of fire-bombing, were sending photo images and tweets describing exactly what was going on before the Metropolitan Police themselves knew the facts. “This is an embarrassment,” police commissioner Sir Paul Stephenson acknowledged.

In any event, the public believes as a rule that it knows enough to believe that the government isn’t telling it the whole story — which is almost always the truth.

The flattening of the communications landscape has moulded expectations of a public used to Googling for the facts it wants and also susceptible to conspiratorial blogs. The public expects the right to be told the truth.

For Gowing, there is an everwidening gap between public perceptions and the slow pace of power systems to respond. This is creating a new “deficit of legitimacy.” Gowing is convinced this is changing the relationship of the people to the state, and also to corporations. BP management learned the hard way from the Gulf of Mexico debacle what “they didn’t realize.” Government agencies, cabinet offices and other institutions are now striving to “realize what they don’t realize.” What sort of behavioural change will emerge in the way of more systematic transparency, however, is not yet clear.

But however much we believe that delicate diplomacy should not be hostage in the future to aggressive Internet warriors, capable of destructively leaking damaging material or organizing cyber-attacks on Web sites of players whose policies they object to, the general development toward greater transparency is the crusade to which Assange has given his radical leadership. The accounts of bribery, corruption and criminal behaviour, including by prominent Western corporations, make it hard to argue that the public is wrong to want to know the facts.

So if the content of the leaks hasn’t exactly changed the world, the whole episode is giving some clarity to very major changes in the world. It will take balance and insight to keep them positive.

Photo: IB Photography / Shutterstock