Change occurs gradually, unless poked by some triggering event. In Canada, the pension regime has evolved slowly but surely since Old Age Security (OAS) was introduced in 1952. Major milestones along the way include the introduction of registered retirement savings plans (RRSP) in 1957 and the registered retirement income fund (RRIF) in 1978, the creation of the Canada Pension Plan (CPP)/Quebec Pension Plan (QPP) in 1966, and the Guaranteed Income Supplement (GIS) one year later. The major change in recent years was the overhaul of CPP’s/QPP’s funding formula in 1996 and the creation of the Canadian Pension Plan Investment Board (CPPIB) in 1998.

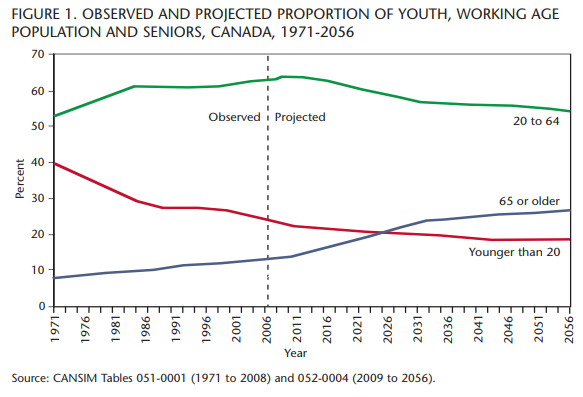

Now, in 2010, governments may be poised for another significant change to Canada’s pension system — change triggered in large part by the 2008 financial downturn, which savaged the retirement savings of a generation about to retire (figure 1).

The ensuing “panic” may have subsided now that the recession has been declared over and investment markets have begun to revive, but the warning bells are still ringing. There may be vulnerabilities in our current system and, if so, it is right for governments to consider ways to address them.

The underlying question, of course, is whether Canadians are saving enough for retirement — whether they will have saved enough to have the income they need to fund the lifestyle they desire during retirement.

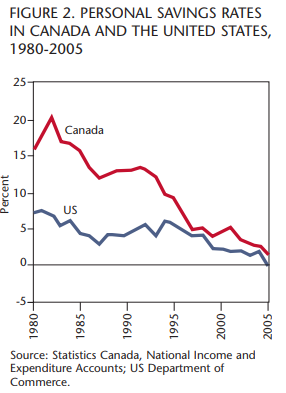

Canadians are saving considerably less than they were. As we emerged from recession in 1982, the savings rate climbed to more than 20 percent. It has been dropping ever since. In 2005, Canadians set aside just 1.2 percent of personal income for a rainy day. (The savings rate has since rebounded to 4.8 percent in 2008, demonstrating that, in times of economic uncertainty, people tend to save more; see figure 2.)

Is this enough?

Members of Canada’s baby-boom generation who begin turning 65 next year may have cause for concern. Canadians are living longer, healthier lives — which means they will need more to sustain them in a long and active retirement. For every couple hitting retirement age this year, it is likely that one of them will live to see his or her 90th birthday.

Today’s boomers have other reasons to worry.

- Only about 38 percent of Canadians are covered by a registered pension plan (RPP). While many of these are defined benefit (DB) plans that provide guaranteed income for life, defined contribution (DC) plans, which are becoming the norm, put an extra burden on individuals not only to fund their retirement savings adequately, but to manage those savings effectively, as well — an issue highlighted by last year’s market crash.

- The financial costs of care-giving are rising rapidly, which means there will likely be a need for additional savings in future — not only for the boomers themselves, but for their parents, who are also living longer. The financial needs of this so-called sandwich generation would appear to be greater than any other generation before.

- The lifestyle expectations of today’s retirees are also likely to be more costly than any previous generation — throwing into question traditional rules of thumb about what proportion of their income requirements today will need to be replaced in retirement.

- And, while it may not worry them, boomers are carrying more household debt than any generation before them. Their parents strove to enter retirement free of debt, but today’s pre-retirees do not seem fazed by the prospect of having a mortgage. Household debt-to-income levels have hit a record high of about 145 percent.

To be clear, Canada’s seniors are not headed for the poor house. The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) said Canadian seniors were number three in the world with regard to their income prospects in retirement — less than 5 percent of Canada’s seniors were living below the poverty line in the OECD’s 2009 study, one of the lowest rates in the developed world.

Likewise, the federal-provincial task force on pension reform, headed by Jack Mintz, did a careful investigation of Canada’s pension regime and concluded late last year that a major overhaul may not be necessary — the system is working just fine. Even the government of British Columbia, one of the strongest advocates of bringing in a new supplemental pension plan, has suggested taking more time to craft an effective, national plan to help those who are not saving enough for a decent retirement.

If there is not a crisis, however, there is still room for improvement, and it would be unfortunate to allow the developing momentum for change to falter because the perceived urgency has diminished. Maybe the system as a whole isn’t broken, but parts of it still need to be modified. Are there things we can reasonably do now that will improve the lot of those about to retire over the next five to ten years — and be good solutions for everyone else after that?

For these pre-retirees, the big question is this: What proportion of today’s income will they need once they hit retirement?

As a rule of thumb, most financial planners use 70 percent as the target income replacement ratio — if you earn $70,000 per year in your working years, you will need about $50,000 to maintain your lifestyle in retirement. This presumes that people who are no longer working spend less on such things as business clothing, commuting, fast food and prepared meals. Some academics argue that a 60 percent income replacement ratio is adequate for most people — and for higher income earners, some say the replacement ratio could be as little as 50 percent.

While these rules of thumb may have worked in prior years, it remains to be seen whether they will still be valid in future — especially given the boomer generation’s lifestyle expectations and the unpredictable course of future health care costs. (If nothing else, it is clear that a “one-size-fits-all” approach to retirement planning is overly simplistic.)

Yet boomers have probably accumulated more wealth than any before them, notwithstanding any hit to their investment portfolios and despite their low savings rate of late. The equity in their houses alone represents a significant nest egg.

In our view, Canadians should be able to choose when to begin withdrawing money from their RRSPs. This will give them more flexibility and allow them to accumulate more retirement savings (in their own plans, or their spouses’). And to be clear, it’s not a question of “if” the government will get its deferred taxes, but “when.”

It makes sense, therefore, to focus on improving what they can do with what they already have, rather than introducing major design changes to the plan — which may benefit younger people but not have much impact on those about to retire.

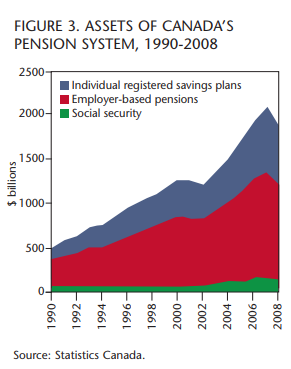

Canadians generally rely on three components for assistance with their retirement income: government pensions, employer pensions and personal savings, commonly known as the three pillars. The first pillar provides direct assistance from government through the CPP/QPP and OAS. The second provides assistance from our employers who contribute some or all of our company pension contributions. The third provides assistance through tax deferrals when our personal savings are invested in an RRSP (figure 3).

Low-income Canadians may have only government pensions to rely on. The maximum an unmarried 65-year-old will earn from CPP/QPP and OAS is $17,413 for 2010; married individuals will receive $34,800. In addition, it is worth noting that only one-half of all Canadians have an occupational pension plan and up to one-third of Canadians do not contribute to an RRSP.

For those who have accumulated retirement assets in DC pension plans and/or RRSPs, their annual retirement income will be a function of how much they have set aside. In essence, the way they pay for retirement involves converting their retirement savings, their investments, into an income stream. And as it stands today, this conversion process is simply not tax efficient — regardless of the conversion option they choose: RRIF or annuity.

If governments are going to review pension adequacy, we believe they should also include a review of the current personal saving regime. With this in mind, we offer five concrete suggestions for RRSPs and RRIFs that would be of immediate benefit to people entering retirement or recently retired, as well as being helpful to younger adults as they plan for their own retirements.

The bargain we strike with the government when we set up an RRSP is this: the government permits us to defer income tax on our contributions, allowing the savings to grow within a tax-sheltered plan, in the expectation that the tax will eventually be paid when the savings are withdrawn — probably at a lower marginal tax rate. The conversion age for RRSPs is 71. By the end of the year that plan holders reach their 71st birthday, they must cease contributing to their RRSPs and convert them into RRIFs or annuities — the logic being that, having allowed Canadians to defer tax while their retirement savings were accumulating, the government needs to be sure that the money will be withdrawn, allowing it to recoup some of the deferred tax.

There is one exception to this rule. A spouse can continue making contributions to a spousal RRSP as long as the younger spouse is under the age of 71. For those without a spouse, this option to extend one’s ability to garner tax-sheltered retirement savings does not exist.

As Canadians live longer and work longer — and save longer — they may feel it is premature for them to cease saving and begin making withdrawals as early as 71. Unnecessary (and unwanted) RRIF payments may even trigger OAS claw back, causing some seniors to forfeit some or all of the government benefits they might otherwise have received.

In our view, Canadians should be able to choose when to begin withdrawing money from their RRSPs. This will give them more flexibility and allow them to accumulate more retirement savings (in their own plans, or their spouses’). And to be clear, it’s not a question of “if” the government will get its deferred taxes, but “when.” The money will be withdrawn eventually, one way or another, which means the government will still have its opportunity to collect tax revenue.

As noted earlier, RRSPs were designed to be tax-deferral plans — a way to convert current income into future income so as to defer taxation from today to some time in the future, usually during retirement.

Under current progressive tax rates, the higher one’s income, the higher one’s marginal tax rate. The underlying assumption regarding RRSPs is that contributions and the income they earn would attract a higher rate of taxation than the later withdrawals. This assumption may not always be true.

Ideally, individuals begin saving for retirement when they are young — typically at a time when their incomes are lower, and so is their tax rate. By the time they convert their RRSPs, they may be in a higher tax bracket than when the contributions were made.

Withdrawals from RRIFs are taxed as interest/salary income — even if the growth in the plan was derived from a combination of dividends and capital gains. Had this growth been achieved outside a registered plan, the income would receive preferred tax treatment resulting in a lower tax rate.

In our view, only RRSP contributions themselves should be taxed as “deferred employment income.” The investment returns (i.e., the growth in the plan) should be taxed at a lower rate that mimics the tax rate that might have been paid if the investments had been held outside a registered plan.

In addition, we note that the loss of the preferred tax status for dividend income and capital gains held in an RRSP may skew one’s investment behaviour. The very nature of the tax treatment is an incentive to opt for an abundance of interest-bearing securities in one’s RRSP portfolio; at today’s all-time-low interest rates, such investments will grow very slowly and one’s retirement savings may not even keep up with inflation on an after-tax basis.

Currently, on death, the balance of the plan would be included in that year’s income of the deceased, and only the net after-tax amount is passed on. The balance of an RRSP or RRIF is transferred tax-free to a spouse or common-law partner (or, under certain circumstances, and with conditions, to a dependent/disabled child or grandchild). In effect, the law permits the tax to be deferred a while longer, until the survivor withdraws the funds or dies. No provisions exist, however, for a tax-deferred rollover to anyone else.

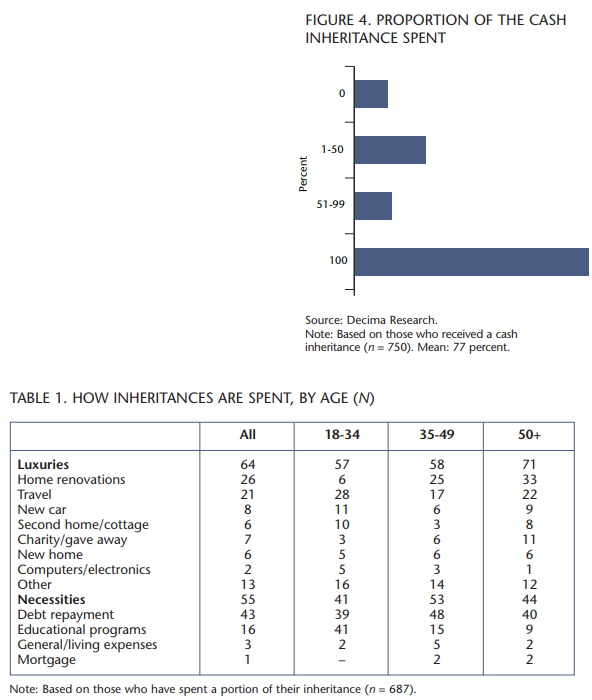

Under current rules, there is no incentive to use the inheritance (or whatever is left of it after taxes) to contribute to an RRSP. In our view, if there are balances in RRSPs or RRIFs when individuals die, these amounts should be allowed to be rolled over tax-free into the next generation’s RRSP or RRIF. If RRSPs or RRIFs could pass untaxed, this would be encouragement to keep the funds in a retirement plan. As it stands, the majority of beneficiaries tend to spend their inheritances rather than re-invest (figure 4, table 1).

Ideally, this rollover should be available on top of any unused RRSP room — but even allowing it to be used to top up a plan to its current limit would be an improvement. Based on current trends, it is projected that unused RRSP contributions will exceed $1 trillion by 2018. The parents of many boomers are still alive and much has been written about the magnitude of the so-called inter-generational wealth transfer. Such a policy change could therefore be of benefit to many Canadians approaching retirement age. And, as with the earlier argument regarding age restrictions, such a move would not deprive the Treasury of its tax revenue; it would merely defer it a while longer.

If there were real concerns that this would stretch out the tax deferral too long — from one generation to the next ad infinitum — the government could create a new registered vehicle to receive the proceeds, which must then be paid over a prescribed period.

In addition, we believe that balances in RRSPs or RRIFs should be allowed to roll over tax-free into a registered disability savings plan (RDSP). The government took an important step when it created the RDSP in 2008, and we applaud them for it. Canadians with disabilities can face extraordinary expenses and may be limited in their ability to earn enough to support themselves.

Allowing individuals to bequeath their RRSP or RRIF balances to an RDSP would offer one more way to help people with disabilities live more independent lives.

There are prescribed rates at which funds must be withdrawn from a RRIF. In the first year, 7.38 percent of the balance is withdrawn, in the second year, 7.48 percent of the remaining balance, and so on until age 94, when the withdrawal is capped at 20 percent of the remaining (and presumably declining) balance.

As is the case with the age restriction, this rule forces individuals to make withdrawals from their RRIF whether they need the income or not — for instance, those who continue working into their seventies. They lose their flexibility to do what they want with their personal savings and, more specifically, which of their assets to draw down first.

In addition, the current prescribed withdrawal rates may deplete the RRIF too quickly. It is highly unlikely in today’s investment world that investment returns will keep pace with the withdrawals. It is normal to expect that individuals will begin drawing on their principal as their retirement progresses, but they are more likely to outlive their investments if forced to make large withdrawals early on.

For these reasons, we believe the government has an opportunity to extend the life of a RRIF by lowering the rate at which funds must be withdrawn.

Finally, we question whether the annual contribution limit is reasonable under current circumstances. As it stands, Canadians can contribute up to 18 percent of earned income up to $122,222, that is, to a maximum of $22,000 for 2010. Unused amounts can be carried forward. However, if the investments in your RRSP don’t perform as well as expected, there are no provisions — as there would be for the administrator of a DB plan — to make additional contributions to ensure your retirement is funded to the desired level.

For those earning more than this year’s maximum, they could argue that they are being forced to undersave for retirement — or, at least, are not being given the same advantages of using RRSPs to save for retirement.

The rules also favour households. For example, a couple earning a total of $150,000 ($75,000 each) would be permitted to contribute a total of $27,000 to their RRSPs, while the single taxpayer earning the same amount — $150,000 — would be permitted to contribute only $22,000.

In our view, contribution limits should be broadened to be more comparable to DB pensions and to offer ample opportunity for all Canadians to save equally for retirement.

While others are focusing on broader pension plan reforms, we believe the personal saving component cannot be ignored. We believe that the three pillars on which we rely for retirement income are sound. Major surgery is not required, but like the boomers themselves, Canada’s pension system is reaching an age where elective surgery may improve its health and make retirement more pleasant. In the longer term, the approach we propose — which is based on the principle that individuals should have the flexibility to manage their retirement savings in the most tax-efficient manner, according to their individual circumstances — will make for a healthier pension regime.

Photo: Shutterstock