For centuries, traders and travelers from around the world have marvelled at China’s complexity. Grappling with that complexity now is crucial for Canada’s future, given China’s return to its historic stature as a great power and our reliance on international commerce, our place in a globalized world and our deep people-to-people connections with the Middle Kingdom.

China is on track to become the largest economy in the world within a decade, a milestone that would have seemed impossibly far-fetched just 30 years ago, when it was emerging from the ideology-bound isolation and backwardness of the Mao era.

And now, China is an engine of global growth and has weathered the recent recession less daunted than the major developed economies. Still, the first half of 2012 has seen it buffeted by uncertainty about the sustainability of its growth, the most serious political crisis since Tiananmen Square and an open contest between further liberalization and a revival of Maoist state supremacy.

Against that backdrop, China is grappling with ongoing challenges on a vast scale: enormous income disparities, corruption, pollution, a spotty social safety net and an aging population, among others.

While the pace and scope of its economic development have been breathtaking, a continued, upward trajectory is not inevitable. The Chinese “model” is under pressure. Practically speaking, the model has nothing to do with communism but is based on a pervasive control by the Communist Party of China. For the party, governing China is a juggling act on multiple, competing levels: maintaining stability and high-velocity growth; protecting the preeminence of the party while rolling back corruption and addressing increasing expectations of Web-enabled citizens for transparency, accountability and legal rights; and looking inward to manage an array of domestic tensions while also looking outward as China grows back into the role of a global power. Policy-makers have been trying to cool its overheated real estate market and lower the cost of home ownership, without crashing an enormous sector that underpins a substantial piece of the national economy and global economic growth. Any of these — and other — balls in the air could be dropped at any time.

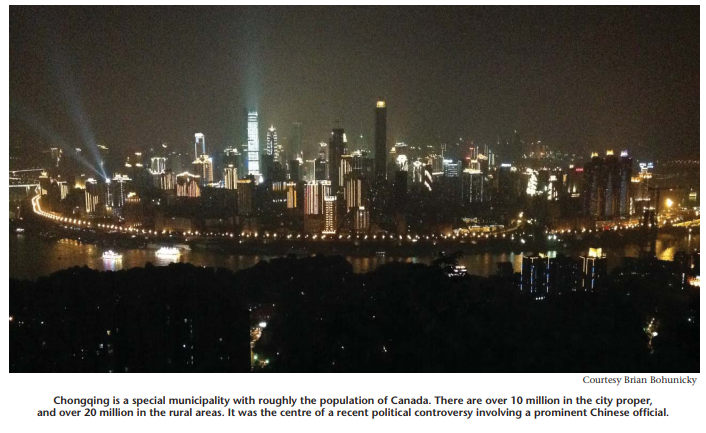

Furthermore, maintaining consensus within the party leadership on all major matters is a fundamental challenge in itself. That consensus proved to be a thinner veneer than is often assumed when the grave issues concerning former Chongqing party boss Bo Xilai erupted early in 2012, during the sensitive lead-up to a decennial changeover of top leaders. Regardless of the outcomes, it’s a safe bet that China’s global impact, including on Canada’s well-being, will continue to increase. The Chinese market is a driving force behind global commodity prices, the cost and quality of consumer goods, and foreign investment — all pillars of Canada’s current and future prosperity.

China’s rapid growth has driven up the prices of what we sell and driven down the prices of what we buy. That has improved our standard of living across the board. If the skeptics are right, and China is headed for a hard landing and disruptive instability, we’re in the fallout zone. More likely in the medium term, the dust will settle and cautious liberalization will advance at a pace the party will continue to modulate, with GDP growth in the mid-single digits. Canada’s choice, if China’s rise does continue, is between rising with it or stagnating on the sidelines.

China is on track to become the largest economy in the world within a decade, a milestone that would have seemed impossibly far-fetched just 30 years ago, when it was emerging from the ideology-bound isolation and backwardness of the Mao era.

This is not about whether China will supplant the United States as the world’s superpower. That’s a role defined in the terms of another time and another nation. There is no simple substitution of the chess pieces on an old board. This is a new game. China is singular, and various dimensions of its development are without precedent. It is not “supplanting” anything that came before. University of British Columbia China expert Paul Evans talks about “two suns in the sky” and the gravitational implications of the two powers circling each other in a planetary system that until very recently had just one sun. China’s influence in global institutions and on a range of multilateral issues is catching up with its economic might. Its continued rise — or its faltering — will define this century, and likely beyond. How the story plays out will shape new dynamics in the world and will require new thinking, innovation and adjustment by other nations.

That reality demands much greater seriousness about China in Canada. We need to know more, understand more, and interact in a more sophisticated and purposeful manner with China. This is true in government, business and society as a whole.

Canada’s federal government is now pointed in the right direction and favours constructive relations with China. This is positive, and it matters. But if you’re playing in the major leagues, you can’t spend much time celebrating if, after several seasons, your batters figure out which direction to face when standing at the plate. Much, much more is possible, and indeed required, when it comes to federal leadership.

In broad terms, what’s still lacking is a sustained strategic focus, ambition and creativity. The current emphasis on boosting exports of natural resources, especially oil, is fine as far as it goes but, strangely, it is not accompanied by any other economic, environmental or political objectives. Most federal departments should have a substantive and active China agenda, engaging and cooperating with their counterparts in support of a government-wide vision and concrete objectives mandated from the top.

Officials should be building long-term relationships and advancing joint initiatives. The political leadership should set the direction and sustain a priority emphasis. It should also be prepared to defend the necessary costs of foreign travel and engagement activities, because you can’t build Canada’s future in a global economy armed with only a transit pass. Of course, flying economy class might be a necessary concession to frugality and gotcha journalism.

Good ideas have been advanced for conceptualizing and acting on a 21st century relationship with China and other major emerging economies. Recently, Dominic Barton, Yuen Pao Wu and Rana Sarkar contributed to that body in the Canada 2020 publication The Canada We Want in 2020. There are some important common threads running through their lists of recommendations and various other recent reports and proscriptions. Some of these are the following:

- Canada is behind its competitors in forging links with China and should be playing catch-up;

- The federal government should lead, convene and consolidate in areas where there are useful but scattered efforts by other players, and it should foster networks that transcend the public, private and nonprofit sectors, rather than relying solely on the traditional government-to-government rituals of 20th century diplomacy;

- Commerce should be the central priority, with a focus on key sectors, but there should also be greater federal government emphasis and leadership in other relevant fields, including education, science, cultural exchange, environmental policy and technology, and governance;

Much more can and should be done in the realm of “people-to-people” linkages and bilateral human capital concerns, accompanied by federal action to raise levels of awareness and knowledge about Asia in the Canadian public (including language skills) and to advance Canada’s brand in China and other major Asian markets.

Directions like these could underpin a forward-looking, long-term China strategy for Canada, driven by both ambition and realism. However, the prospects of this happening soon are remote. Such an approach assumes a particular concept of the role of government that is not currently operative in Ottawa. A proactive strategy that empowers stakeholders at all levels, promotes “soft power” initiatives, and mandates and resources our diplomats to do more than traditional diplomacy is wishful thinking when the dominant paradigm is defined by useful but limited trade agreements, largescale military deployments, minimalist government and nostalgic symbols such as the monarchy. Those seeking to play “catch-up” in our relationship with China will, for the foreseeable future, continue to rely on the varied efforts of committed players across various sectors beyond government, including academia, culture and, of course, business.

It is simply not the case that every business needs to venture into the Chinese market. But certainly Canadian business in general needs to step up to the plate more assertively, bringing to bear a long-term approach to building mutually beneficial relationships with counterparts in China. The limited Canadian presence there today is one manifestation of our broader productivity problem: too many exporters stick with the familiar but declining US market next door, avoiding higher risk/ higher reward pursuits in China and other emerging markets that demand more learning and adaptation.

It’s a safe bet that China’s global impact, including on Canada’s well-being, will continue to increase. The Chinese market is a driving force behind global commodity prices, the cost and quality of consumer goods, and foreign investment — all pillars of Canada’s current and future prosperity.

The most fundamental adaptation that Western business people must internalize for success in China is the centrality of personal relationships. Before introducing a company or a product, they must first introduce themselves and form relationships of trust and respect that will be a foundation for doing business safely and profitably. In the West, we are accustomed to developing friendships with people we are doing business with. In China, the opposite process holds sway — you develop business opportunities with friends.

China has been modernizing rapidly, of course, and international standards and practices have become more prevalent. But the change is taking place on Chinese terms and in the context of Chinese culture and history. The rule of law is evolving. Contracts and legal procedures exist, and they matter. But a contract alone is insufficient for doing business there. The mutual obligations that operate within networks of friendships are fundamental. The business culture is a complex blend of the traditional and the ultra-modern.

Navigating it requires a sustained and upfront investment of time, learning and relationship-building that many Westerners neglect to their detriment.

The intertwined presence of government, party and business is another feature of the landscape in China that foreigners must take into account at every turn. The rules of the game are different. Some would say it’s a different game altogether. The dividing lines between the public and private sectors and between party and government are entirely different as concepts from those Western business people are familiar with. Again, policies and practices in China are evolving, but the model is distinct and is likely to remain so in the years ahead. That means that even the largest corporate giants cannot do business in China in the same way they have done it elsewhere and expect to succeed.

As a society, Canada has some distinct advantages and considerable opportunity to leverage its brand in China. We are a Pacific nation, blessed geographically with a gateway position between Asia and North America. The Canadian population includes the peoples of the world, particularly one of the world’s largest concentrations of ethnic Chinese. Toronto and Vancouver are especially influenced by this presence, culturally and economically, with many of these Canadians spending significant amounts of time in both countries. These are powerful connections in an era when connections matter more than ever.

It also matters in China, still, that Canada was never a colonial power; that the Diefenbaker government arranged the first foreign wheat sales to China; that the Trudeau government led the way for other countries to recognize the People’s Republic of China in the early 1970s; and that we tend to adopt a less patronizing, less arrogant attitude toward China than do many other Westerners. Though the average Chinese person knows little about Canada, they generally associate us with a pristine natural environment, wide open spaces, abundant resources, an advanced economy, good education and high standards of living. They still remember the legendary Dr. Norman Bethune and the equally legendary Dashan — Ottawa native Mark Rowsell, a masterful speaker of Mandarin and entertainment personality known and loved apparently by everyone with access to television in China.

There are worthwhile people-topeople contacts taking place at all levels every day between Canada and China. Our universities, particularly the leading business schools, are increasingly actively recruiting Chinese students and cooperating with counterpart institutions in China on research. Elected representatives and senior officials from provincial governments and large cities frequently travel to China to promote trade, investment and cultural exchanges.

And yet, in a place as vast — and vastly complex — as China, Canada’s impact is quite modest, even in comparison with smaller countries like Australia. And nobody stands around waiting for Canada to show up.

In addition to creating new opportunities for more impact, through measures like those mentioned above, Canadians could take greater advantage of opportunities already passing under our noses. For example, China sends a steady stream of delegations here (and around the world), often consisting of very senior players in a wide range of fields. Despite their stature, they often go almost unnoticed in Canada. Changing that would take greater knowledge of how China is organized and greater initiative on the part of leaders in the private and public sectors here. It’s an underexploited opportunity for the kind of relationship-building that is invaluable for working with China.

Greater knowledge and sophistication in our media coverage of China would also contribute considerably. It’s a matter of both quantity and quality. When our news outlets do take notice of events, it’s often with a dark cartoon, all menace and plotting. It is not that there aren’t serious concerns with modern China. There are, and we should try to understand them. The key issue is that almost nothing is black and white. There is seldom a single truth about anything, and you have to consider the contradictions. But if we’re going to have a more grownup relationship and some positive influence, we will need a greater awareness of what’s happening in China and a greater understanding of the nuances, and in this the media could play a useful role.

A mature outlook on China might take root if the public debate, to the extent it exists, moved beyond simplistic dead ends. Too often, the loudest voices are peddling either/or clichés: if you’re pursuing trade, you’re indifferent to human rights; foreign investment from China is either a threat or a windfall; we have to choose between the United States and China for economic ties; China must choose between state control and Western capitalism. The issues are actually much more subtle, and navigating them effectively requires respect both for the historical context and the complexity of the dynamics in a land very different from our own.

Rapid change seems to be a permanent feature of our world, and you don’t have to go out on a limb to assume that China will be an increasingly important driver of it. Canadians have compelling reasons of opportunity and necessity to pay a great deal more attention to China. Extracting and shipping our natural resources there at ever-greater speed is not a sufficient strategy to secure prosperity for coming generations. Resources are certainly among our greatest assets, and their responsible and strategic exploitation should of course play a central role in our economy. But we have so much more to do. In China, commerce is fundamentally about relationships. Our real opportunity lies in fostering a broad range of human interconnections in the public and private spheres, interconnections that are fed by innovative public policy, long-term strategic thinking, greater sophistication and deeper knowledge.

It’s a timely challenge. China is in a historic period of transition as it grapples with enormous economic, social and political problems and as a new generation of top leaders prepares to take power. Choices are being made and directions set. Canadians would be wise to take advantage of every opportunity to engage now and in the coming years.

Photo: Shutterstock