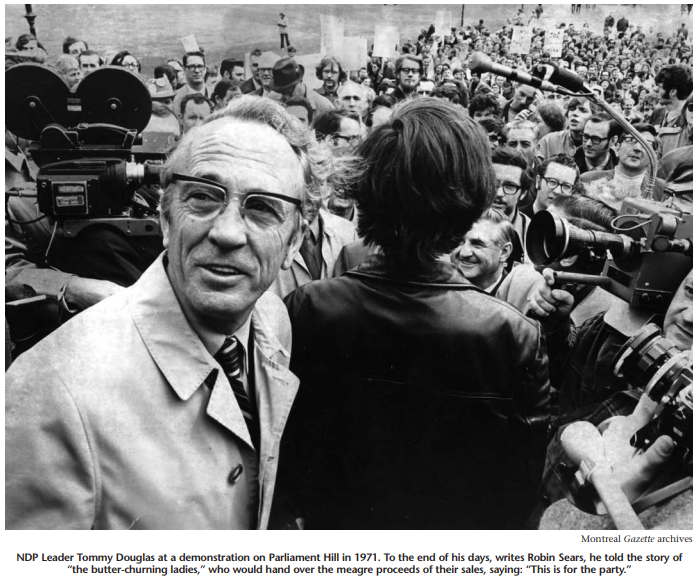

Until the end of his career in the 1980s, Tommy Douglas used to delight audiences with this story about the butter-churning ladies of Weyburn, Saskatchewan: In the depths of the bitter Depression years on the farms in the drylands in the south of the province, a group of women would work together to churn butter from their small herds of cattle. They held back from the kitchen table one pound of butter for every five; when they went to town they sold what they had set aside and saved the nickels and dimes they earned.

At the end of another long Depression winter, Tommy came to town to deliver one of his hour-long harangues against the Canadian-Pacific Railway, the Winnipeg grain cartels and the pain of private medicine. Near the end, he would recount the parable of the butter-churning ladies. With mounting emotion in his voice, he recalled his astonishment as the leader of the group approached him with a little swatch of calico carefully wrapped around the proceeds of their months of hard work. “This is for the party, Mr. Douglas. Me and the ladies saved it from our butter sales. You put it to good use, now,” the leader would earnestly instruct as she handed over their proud little pile of silver.

Nearly half a century later, Douglas would shake his head in astonishment at the memory. He would describe his astonishment at their commitment and his embarrassment at their zeal.

Then he would yank the guilt levers of these far more affluent audiences of the 1970s and 1980s, describing the desperate poverty of the women and their families. Then he would deliver the punchline, and you’d hear gasps and sobs from every corner of the room. Impersonating the butter ladies’ leader and her fury at his patronizing impertinence, he would say:

That is not your decision, to make, Mister Douglas. We earned this money through our hard work. This is our party and our movement, Mister Douglas. You are only our elected leader. You take this money of ours and you… you just make sure you use it well!

He would stop and look appropriately ashamed at the memory of his youthful temerity, and the crowd would erupt. The passed hats would quickly fill with “silent money.”

John Diefenbaker was similarly golden-tongued in capturing his audience’s rage at their powerlessness in the teeth of poverty and rural isolation, of the unfairness of the political system to people like them.

Dief put himself at the centre of these morality plays as the advocate of the honourable but battered fathers and mothers, struggling for justice against hidden, powerful and distant string pullers. His listeners knew his parables were thinly veiled attacks on the alignment of big business and the fiercely partisan administrations of Jimmy Gardiner in Regina and Mackenzie King in Ottawa. And his lieutenants would tithe the faithful with as much rigour as any CCFer.

Douglas and Dief used the power of their oratory to educate two generations of Canadians about democracy and its discontents. Their civics classes, disguised as tirades against unfeeling officials and heartless corporate managers, hammered home two important lessons: You can make a difference in politics with even the nickels you earn from selling butter, but you need to support a powerful champion and advocate to deliver the justice you seek.

They were also defending the importance of grassroots political finance.

In the cracked lens through which we regard politics today, the issue of how we finance our democracy and the role of advocacy in it are each seen as the sleazy and embarrassing sides of partisanship and government. Campaign finance and lobbying are ideological footballs, kicked one way by conservatives, in defence of their claimed anti-government convictions, kicked back by progressives, as the centre of their nightmarish tapestry of a dark corporate conspiracy against working Canadians.

From the ivory tower, retired academics like W.T. Stanbury, channelling the realities of another era, decry campaign finance and government lobbying as the two sides of “the influence-peddling coin.” From the indulged aerie of newspaper editorial pages, money for politics is denounced as little different from money for drugs, guns or gambling. For self-proclaimed democracy activists, lobbying government for change is akin to the curbside solicitations of working girls.

Douglas and Dief used the power of their oratory to educate two generations of Canadians about democracy and its discontents. Their civics classes, disguised as tirades against unfeeling officials and heartless corporate managers, hammered home two important lessons: You can make a difference in politics with even the nickels you earn from selling butter, but you need to support a powerful champion and advocate to deliver the justice you seek.

This Grimms’ fairy-tale view of democratic life is dangerous. It undermines public confidence in two of the most important threads of a political culture committed to “government of the people.” Academics and editorial writers know well the cost of partisan politics. The legitimate expenditures of candidates and parties on salaries and airplanes and television are necessarily in the tens of millions in a country as vast and diverse as Canada.

Equally, they understand — and when their interests are affected they even employ — lobbyists and their role. Advocates on behalf of a financially strapped university or an embattled news organization being hounded by the taxman can’t depend on lawyers or the courts alone to press their case. They would be dead and buried before the Canadian legal system delivered them from fiscal hell. Nor can they depend on their own appeals to officials — after all, the matter of what bureaucrat, which department, what message, which lever needs to be pulled, is not part of their professional lexicon.

The byzantine labyrinth that is modern government cannot be navigated by ordinary citizens in their off-hours. Would that it could, but nowhere in the developed world is that more than a nostalgic memory today. The ability of a “few good men and true” to unite and together challenge the power of established partisan machines is also a fiction. Such a crusade takes money, lots and lots of money.

As much as we rail at their failures, no democracy has created an alternative to the broadly based political party as the centre of politics. Like Winston Churchill’s famous backhanded endorsement of democracy itself, large-brokerage political parties are the worst form of party structure, except for all the others. Parties based on ethnicity, language, regional pride or personality are the bane of emerging democracies around the world.

To survive, parties depend on an ability to mobilize financial resources quickly and effectively, to attack each other or to defend their own members and candidates. When the Progressive Conservative party lost that ability, following the rise of the Reform Party and the Bloc Québécois, it collapsed. When Stephen Harper and friends took over the right-wing remnant that had morphed into the Canadian Alliance, they understood that imperative in their bones and quickly turned to building the most sophisticated fund-raising apparatus ever created in Canadian politics.

In a Canadian polity of which nearly two-thirds shares few of its values or policy aspirations, the new Conservative Party has won power, held it for five years, and remains the richest and most powerful political machine in the country. Harper and his crew did it by recognizing one traditional verity of fundraising and combining it with the magic of modern technology.

Political fundraisers in rotten borough campaigns in nineteenth-century England knew that however tempting it was to rely on the sponsorship of a rich family or two, rather than having to do the tedious work of passing a hat around a dozen meetings of less wealthy supporters, it was not wise. A disgruntled or suddenly bankrupt sponsor left you and your candidate instantly vulnerable.

The Liberal Party, which had ushered in public financing in 1974, lazy and hollowed out after decades in power, forgot this truth. The national party became addicted to the easy corporate cream of $10,000 or $100,000, skimmed from a dozen vast and boring dinners annually. At the same time, rich local incumbents fell victim to a more debilitating addiction: guaranteed public funding.

The western insurgents around Stephen Harper knew they could not collect competing corporate sums, so they developed an ability to electronically suck a hundred dollars, several times a year, from tens of thousands of regularly stroked local supporters.

Using sophisticated direct marketing and database management tools, constantly tuned and updated, the Alliance and then the Conservative Party have developed a highly efficient means of using their fundraising apparatus to spread their political message, and then of using their political message machine to feed their fundraising. A ministerial attack on the CBC, the existence of gun-hating Torontonians or whispers of a sinister opposition party coalition might become a series of e-mails, tweets, blog postings and automated phone calls fed into thousands of Canadian homes, which respond with another gush of cash into Conservative coffers. Liberals and New Democrats snarl at the cynicism and vulgarity of this approach to politics, but it is really only envy. New Democrats, after all, did the first national directmail political campaigns in the 1970s, featuring some of the nastiest attacks ever on their corporate and political enemies, carefully targeted by message, messenger and demographic sensitivity. Later, however, that party got lazy as well, with local incumbents fattened on campaign refunds, and the provincial and national parties masking the fall in the number of contributors annually with an increase in the average contribution of their hard core.

It is important to understand these different party histories in trying to unpack the Conservatives’ apparently suicidal attempt to remove federal taxpayers’ direct subsidy of national parties of less than a dollar per Canadian a year, currently about $27 million. It is only one leg of a three-legged stool of subsidies — along with a generous tax credit on donations, and campaign rebates — so why attack it so vehemently?

Too few pundits have dissected the hypocrisy of the assault, aimed primarily at the Liberals and secondarily at the Bloc. If taxpayers’ money being used to subsidize politics is evil, then why aren’t the Conservatives in favour of kicking out all three legs of the campaign finance stool? For that matter, should they not promise to pay back the tens of millions their members of Parliament also receive to support their offices, their travel, their staff salaries, not to mention the infamous “ten percenters” — the increasingly nasty taxpayer-funded flyers that politicians send into the ridings of their political opponents? Why is one form of subsidy impure and others not?

It is a mark of the shrewd political skill of Senator Doug Finley, today’s Conservative equivalent of the late Liberal Senator Keith Davey, that the Tories have been able to pull off this clever stunt. He is the author of the demand, launched in 2008, that the subsidy be scrapped as an indefensible fraud on taxpayers. The Conservatives escaped having to explain the glaring contradiction in their principled defence of the taxpayer that some subsidies are virtuous and others wicked.

In the delicious-irony-of-politics department, the Conservative attack machine has flailed the coalition parties’ dependence on national subsidies, while their fundraisers have recycled those attacks into appeals for cash below the radar. It has been among their most lucrative messages of the past two years.

Why ironic? Well, the Conservatives’ average contribution is less than $100, and every loyal supporter gets $75 of that back from Her Majesty’s treasury in one of the world’s most generous tax credit schemes for campaign finance. So in response to an attack on the evil of using taxpayers’ money for political parties, three out of every four dollars raised comes from the taxpayer. Neat.

But the Tory scheme is adroit on two other levels at the same time. The first is that neither the Liberals nor the Bloc, for reasons too complex and boring to elaborate, have figured out how to duplicate the Tory electronic cash vacuum. The New Democrats are second to the Conservatives in using the system of tax credits effectively and are getting better again after a long time asleep at the switch. So the Conservative attacks target their two most hated competitors, while leaving the New Democrats — on whom they depend to weaken the Liberals nationally — relatively unscathed.

Harper also understands, as a politician with a long view and a deep understanding of Canadian political history, that becoming dependent on a system of national subsidies would be death for his organization. The Conservatives are the biggest beneficiary of the current system, getting more than all their competitors combined in quarterly cheques. This provides a self-abnegating, virtuous veil to their determination to kill the system.

But as a leader determined not to let his party suffer the rot of power that finally did in the Big Red Machine, Harper wants his caucus and party bureaucrats to understand that they must always depend on tens of thousands of small donors for survival. That dependence keeps them connected to their base, serves as a powerful messaging/cash extraction infinite loop, and ensures that those at the centre don’t get fat on a guaranteed income insulated from political performance.

And in terms of good public policy, as well, he is right.

When Canada created its political finance support system it looked at the existing European systems, most of which depended on funds flowing from the taxpayer to the national party centre and distributed locally from there. Few had any form of tax credit or earned benefit mechanism, such as a tax checkoff. In the largest European democracies those systems funded vast party bureaucracies and weak local activism.

As the Kohl scandal in Germany and many others across southern Europe in the past two decades have brutally revealed, those systems did little to stem the flow of illegal cash into their politics. French politics, most painfully, has endured rich party bureaucrats attempting to frustrate the rise of popular outside candidates, and rich insiders revelling in luxury apartments, yachts and bank accounts, funded out of surplus illegal campaign contributions; incredibly, some of the millions of euros flowed from state-owned corporations.

In Canada, when the Commons committee that designed the Canadian system (with the help of a small group of astute academics led by K.Z. Paltiel) elaborated the principles that underlay Bill C-203, first employed during the 1974 election, it rejected the temptation of cash to national parties outside of campaign spending. The committee was wise. When Jean Chrétien threw out that prohibition in an effort to disable the corporate cash machine of his internal enemy, Paul Martin — and, he thought, the Conservatives at the same time — he was unwise.

The original political finance system rested on four central pillars. The first was that disclosure was the most powerful cleanser of corrupt money in politics. If you make it a serious crime to hide a contribution, you help stem the flow by raising the risk/reward ratio for both solicitors and donors.

The second was that a level playing field depended on controlled spending, not giving. If you could buy only your share of 74 minutes of national television time in a campaign, and the price was set by negotiation at a rate that was not extortionate, there was no point in raising an extra $5 million. So forbidding rich donors from giving more than a small multiple of a thousand dollars, as Chrétien and then Harper did, was not necessary, and it avoided making an ass of the law by legislating something you could not ever enforce.

The main reason that the American system has so sadly slid back into a robber baron form of corrupt political finance is the cost of campaigns. Television stations typically double and triple their political ad rates during campaigns, and desperate candidates buy up to half of all the available station ad time in tight races. In combination with the cost of consultants, pollsters and staff, this has driven the cost per voter of American campaigns to nearly five times that in our campaigns. In the 2012 campaign cycle it is estimated that each of the national presidential campaigns will spend more than $1 billion. That is nearly $10 per vote, and rising fast, and it does not include the several hundred million dollars of so-called independent expenditure sanctioned by the US Supreme Court, which is also exploding. Depending on what you count in a Canadian federal campaign, we spend between $2 and $3 per vote, and the amount is relatively stable.

The third pillar was that Canadians should be given a strong incentive to participate in politics through their tax system, and the parties and candidates who showed the best hustle in getting their message out would be rewarded, along with their supporters. This meant that, outside of the campaign period, no donors motivated equalled no subsidy for you.

Finally, the wise legislators realized that to keep the field level over time would require paying back some of the candidate and party campaign spending. Without that debt-levelling mechanism between campaigns, some would develop big bank accounts and others would stagger into bankruptcy and then political irrelevance following a defeat. Parties and candidates in every system and every party borrow heavily, spend fast and pray for victory. Promised contributions evaporate before the dew on the morning following defeat.

The overarching goal of our system, like that in every other democracy, is to attempt to remove the smell of dirty money from politics, while preventing any party from creating a permanent tilt in the political playing field. For a generation, our system was a model for the world. Attempts to tinker with it, first in the 1980s and then, more brutally, in recent years, have wrecked the delicate balance its founders had crafted.

Forbidding unions and corporations from contributing to politics is as futile as banning purchased sex, and for similar reasons. But this was what Chrétien did in his 2003 campaign finance reform. The ban on corporate and union donations, and the $5,000 cap on personal donations clearly took René Lévesque’s 1977 Quebec reform as the model. In return for giving up corporate and union donations, in 2003, parties were compensated with $1.75 per vote in the previous election, since increased to $1.95 per vote. In his own 2006 reform, Harper reduced the ceiling on personal donations to $1,100 per year. But in his ill-fated 2008 postelection move that nearly cost him his government, he proposed to eliminate the cash-per-vote clause in the 2003 reform. And in late 2010, he resurrected the idea, promising at least this time to run on it first.

Other elements of the 2006 Federal Accountability Act place severe limits on hospitality that MPs and bureaucrats can accept. But in our audited, media-scrutinized, anonymous Internet whistle-blowing world, any executive who thinks a politician or bureaucrat is going to put their career at risk in return for a mink coat for the wife, let alone gold seats for the Ottawa Senators, has another think coming.

But unions and companies do want the reassurance that a grateful politician gives, and having forbidden them from giving on their corporate account, many now find other ways to do it. Unions grant cars, people, offices and access to private polls; many corporations do the same. Many also suggest to their senior executives what a reasonable personal contribution to the party might be. Are the thousands in “personal” contributions later quietly compensated in expense repayments? The Quebec system is notoriously circumvented in that manner.

If Canadian experience follows that of Western Europe as a result of the recent changes we have made to our system, we will see two trends very soon: more illegal cash and services finding its way into the system, and declining levels of legitimate giving by ordinary Canadians. Parties won’t need to work to get those $100 PayPal donations on their Web sites, and those seeking political insurance will develop increasingly sophisticated methods of injecting money into the system.

One other hole in the political finance fabric that has been ripped wider and wider in recent years is noncampaign spending. This risks becoming our equivalent of the explosion in spending that has undermined American politics. Until very recently, television networks would not allow parties to buy time outside of an election writ period, and the parties didn’t have that kind of extra cash anyway. Along came the Internet and social media platforms as a cheap way to advertise, down came television station standards about political advertising, and up went the parties’ desire and ability to raise the money to mount what Tom Flanagan has sagely dubbed “the garrison party’s permanent campaign.”

So instead of the parties being forced to compete on the power of their message and their craft in spending $20 million over a 37-day campaign, we now have seasonal ad blitzes, by those who can afford them year round. In 2010, the Conservatives raised $17 million, as against $7 million for the Liberals. The next phase will be similar campaigns at the local level by worried incumbents or ambitious challengers. Despite the fact that most research indicates that Canadians tune out such intercampaign political noise-making, a spiralling arms race is clearly underway.

Even if a raised eyebrow is the appropriate reaction to Harper’s claim of fiscal virtue as the motive for his attack on national party subsidies, he is right that our political finance system is breaking down and needs repair soon.

The Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms and the American First Amendment provide a parallel plotline to the evolution of political finance over the past 30 years. Various complainants — famously including, in the 1990s, the leader of the National Citizens’ Coalition, an angry young Calgary militant named Harper — have used the Charter to attack the system. Courts have struggled with the balance between community interest in a fair and clean democratic system and the individual’s right to unfettered expression, including the freedom to spend money to broadcast one’s views. The rough balance that was arrived at here, which was last year struck down by the John Roberts-led Supreme Court in the US, is that you can spend money, in a campaign or out, to promote or oppose a policy, but not a party or candidate.

Extending this principle to noncampaign spending by the parties and candidates seems a reasonable extension. Parties can contribute to the progun campaign ads of the Canadian clones of the National Rifle Association if they choose. They may not say, “Vote for us to protect your freedom to keep a spare Glock in the garage.” We risk having the entire structure collapse if we fail to plug this noncampaign hole in our carefully balanced set of limits and freedoms.

Clearly, if some parties spend $100 million in nightly television and 24/7 digital advertising, year in and year out, it makes a joke of the limit of $20 million in the election period itself.

Since a majority of Canadians have been convinced that limits on donations are somehow more democratic, despite the distortions and temptations to criminal behaviour they inevitably generate, let’s at least raise them to levels that reduce the temptation for honest Canadians to do something stupid. Few Canadians under the old system, or illicitly under the new system, gave more than $10,000 a year to politics. Ontario set a limit of $5,000, centrally, years ago, and our most Presbyterian province has not yet descended into Latin American political corruption.

That seems a reasonable baseline: $5,000 per party, and perhaps $1,000 per candidate up to 10 ridings, per year.

It would be futile to suggest that corporations and unions should be restored to legality in the current political climate. It will take a serious funding scandal to restore political common sense on this issue. It was, after all, only after we were hit by the scandal surrounding the dubious fundraising methods used in the 1970

Quebec and the 1971 Ontario elections, sealed by our shock and horror at the sight of the Nixon Oval Office safe leaking millions of dollars in small bills, that we were able to get our first campaign finance legislation adopted. When a union boss or shamed corporate executive is forced to admit that he has secretly been playing a role in funding politicians, surely coming one day soon, we will come back to our senses.

But we should accept Harper’s suggestion that we get rid of the unconditional national party subsidies — if he will agree to a few compensatory tweaks.

In the days of delegated conventions, political parties played an essential nation-building role in bringing ordinary Canadians from distant parts of the country together regularly. Another modern “democratic” innovation, one-person-one-vote party decision-making, has killed that. The Internet is a low-touch, low-motivation tool for citizen engagement. Debating, drinking and cavorting together are far more powerful and permanent.

The parties should be encouraged tax return to send a small sum to their to bring their activists together more often through a tax credit based on a travel subsidy. Some of the parties already attempt to do this internally, but none of their systems work very well, given the costs involved. Such a system, adequately funded, would consume several million dollars annually of the current party subsidies.

Politics at the street level is a young person’s game. It requires teams free to work 16 hours a day, to travel for weeks at a time, with energy levels and commitment that nearly everyone loses at 30-something. Traditionally, successful parties persuaded, seduced and Shanghaied armies of such political cannon fodder with promises of free beer, good times and pretty girls. Today the professionalization of politics and the declining participation of Canadians of every generation in party life mean those recruitment channels are dying.

Finally, we might experiment with the tax check-off used by the Americans. Their system has faded badly in recent years. Fewer than 1 percent of Americans tick the box on their chosen party. Some say that’s because voters think they will have to pay the few dollars involved themselves. Surely we could design a system that the parties could help promote that would make it clear you were directing public funds to your party of choice. An experiment with a 10-year sunset might be a good test.

For a generation and more, from 1974 to 2003, Canada had a good run with a carefully designed and finely balanced system of political finance. A decade of tinkering — for a range of motives, from naïvely honourable to crassly partisan — have, sadly, crippled it. In combination with the changes delivered by a digital political world, we have a system that now fails to achieve either of its founders’ goals: to level the playing field and increase political participation.

Photo: Shutterstock