Ideally, a democratic government should rest its foreign policy on a societal consensus that establishes the broad outlines of what is desirable or acceptable for its citizens. In the turbulent post-Cold War context, can public opinion constitute a firm basis to support, or even inspire, foreign policy decisions? Although this question is relevant for most democratic countries, the Canadian experience is interesting inasmuch as it can be associated with a political culture in which the values of internationalism and humanitarianism have deep roots. At the core of this consensus lies Canada’s participation in UN peacekeeping operations, and a substantial part of this article addresses this policy area as a litmus test for the stability and reliability of public opinion in a turbulent world.

In the 1990s, Canada was abruptly confronted with the ”second generation” of peacekeeping, as its soldiers were engulfed in the quagmires of Bosnia and Rwanda. Witnessing these crises and the seemingly intractable challenges that lay ahead for Canada’s peacekeepers, several commentators were prompt to announce the death of Canadian internationalism. In their view, the public was retreating to its domestic concerns and turning its back on world problems. Explicitly or implicitly, their comments were tied to the commonly held belief that public opinion on matters of public policy, especially foreign policy, is incoherent, volatile and thus, in the end, irrelevant in the calculations of decision makers.

Are these perceptions well founded? Is Canadian internationalism really falling apart? Is public opinion on foreign policy as brittle, timid, incoherent and volatile as many observers like to portray it? We address these questions by examining recent trends in Canadian public opinion. We find that, contrary to the common wisdom, there is little reason to point to public opinion as the source of a weakening of Canada’s commitment to internationalism.

We therefore question the notion that the Canadian public is incapable of supporting a constructive internationalism in the post-Cold War world. News of the death of internationalism in Canadian public opinion has been exaggerated. Public opinion is not the obstacle to an internationalist policy that many seem to decry. Neither should it be the scapegoat on which the blame for the shortcomings of Canada’s foreign policy is all too often pinned. Rather, we argue that the public must and can be treated as a full partner in the making and implementing of a constructive internationalist policy.

In recent discussions of Canada’s foreign policy, it is increasingly common to hear that Canada is becoming more and more isolationist. This is often attributed to the notion that Canadians themselves are less and less inclined to support international involvement, notably when it comes to interventions in seemingly intractable conflicts or humanitarian crises.

In general, the debate over the rise of isolationism in Canada tends to exaggerate both the extent of change and the baseline from which such change might be measured. Moreover, the politicization of this debate tends to divert attention from a more basic question: Did the end of the Cold War and the cascade of events that have marked the last decade lead Canadians to reexamine the core beliefs that have been the underpinnings of Ottawa’s foreign policy in the last 50 years? In answering this question, the challenge is to measure these core beliefs and to evaluate changes over time in ideas which typically remain latent.

The Cassandras of internationalism tend to work around such difficulty: They simply interpret the ”moods” of the public by extrapolating them from opinions expressed by élites or the media, without expending much effort in verifying whether their claims accurately reflect what the public actually thinks. In this article we take some distance from those who announce the end of internationalism and the advent of a new isolationism by undertaking a more rigorous analysis of one of the key components of this debate, namely the position of public opinion in the last few years when it comes to defining the place and role of Canada in international affairs.

What does internationalism or isolationism represent for the public, and how can we study this issue in a systematic way? For the first question we adopt the notion of ”dominant ideas” as used by Kim Richard Nossal in his 1997 book, The Politics of Canadian Foreign Policy (p. 138). As Nossal argues, any political culture is characterized by ideologies, which he defines as ”more or less systematic ways of thinking, both normatively and empirically, about social, economic and political relationships among humans in society.” From this vantage point, the analysis of public opinion can be based upon the assumption that a large number of individuals in a society””perhaps even a solid majority””share a set of ”dominant ideas,” and that these ideas are likely to shape their views and influence the way they perceive governmental actions in a given policy area.

This position is related to the debate over the place of public opinion in foreign policy. The conventional view, inspired by the writings of journalist Walter Lippmann and political scientist Gabriel Almond in the 1920s and 1950s, holds that public opinion on foreign policy is highly volatile, incoherent and irrelevant. More recently, however, a significant body of research has questioned the empirical validity of the Almond-Lippmann consensus, noting that public opinion on foreign policy tends to be more stable, coherent and relevant than many assume. This does not mean that the public is perfectly informed about international events or that each individual citizen always reacts to events in the same rational way. What it does mean, however, is that the public as a whole tends to hold relatively stable opinions, and that these opinions can change in a reasonable fashion. One of the bases for the stability of opinion on foreign affairs is the fact that it tends to be founded on core values that allow individuals to form coherent, albeit summary, opinions about complex issues, even if they know remarkably little about the details of these issues.

In short, even if each individual citizen may not be a patented expert in international affairs, public opinion generally evolves in reasonable ways, and thus we can infer interesting lessons from a careful observation of its movements.

Although there is a fair amount of evidence that Canada’s international involvement was widely supported by the public during the Cold War, consistent measures of this support are few and far between.

There are several signs that support for an active international role remained strong in the public during the Cold War, but the change in context makes comparisons with recent years difficult. In 1997, a Goldfarb survey showed that 70 per cent of Canadians believed Canada should place a very high (24 per cent) or a fairly high (46 per cent) priority on its role in NATO. In July 1999, after the bombings in Kosovo, the same pollster got a marginally stronger response: 73 per cent believed Canada should place a very high (32 per cent) or a fairly high (41 per cent) priority on its role in NATO. Support for other international organizations has also remained relatively high in the 1990s, particularly in the case of the United Nations, even though its actions have been consistently criticized in the media. Of all the organizations mentioned in the 1997 and 1999 Goldfarb surveys, Canadians gave the highest priority to the UN.

A detailed and very positive picture of internationalism emerges from an April 1998 Compas survey (www.compas.ca), whose conclusions are consistent with our arguments. First, while foreign-policy élites tend to be pessimistic regarding the public’s commitment to internationalism, the survey finds grounds for optimism. Second, this internationalism is more likely to be driven by values than by narrowly defined interests. This leads the public to be critical of policies that place the interests of exporters ahead of the promotion of human rights and democracy. Third, while citizens have been supportive of the orientations of Canadian governments, ”[t]he public believes that the government has done a mediocre job of explaining or communicating its policies.”

On the whole, reports of the death of internationalism in Canadian opinion have been vastly exaggerated. Moreover, the public’s critical assessment of the government’s ability to explain and defend its policies suggests that internationalism persists as a core value of most ordinary Canadians in spite of, rather than because of, the government’s performance in communicating the values and priorities that still guide, willynilly, its foreign policy.

Participation in UN peacekeeping was one of the most visible dimensions of Canada’s foreign-policy commitments in the 1990s, which makes it a fitting test of the hypothesis that public opinion is abandoning its support of internationalism. Support for peacekeeping in the Canadian public dates back to the creation of the United Nations, when a survey found 78 per cent support for participation in the new UN peacekeeping force. This support has remained firm in the decades since, as Canadian troops have been assigned to virtually every peacekeeping mission undertaken by the UN. In the 1980s, more people (between 30 per cent and 40 per cent) mentioned peacekeeping as their preferred priority for the military than mentioned any other role. The end of the Cold War did not affect this preference.

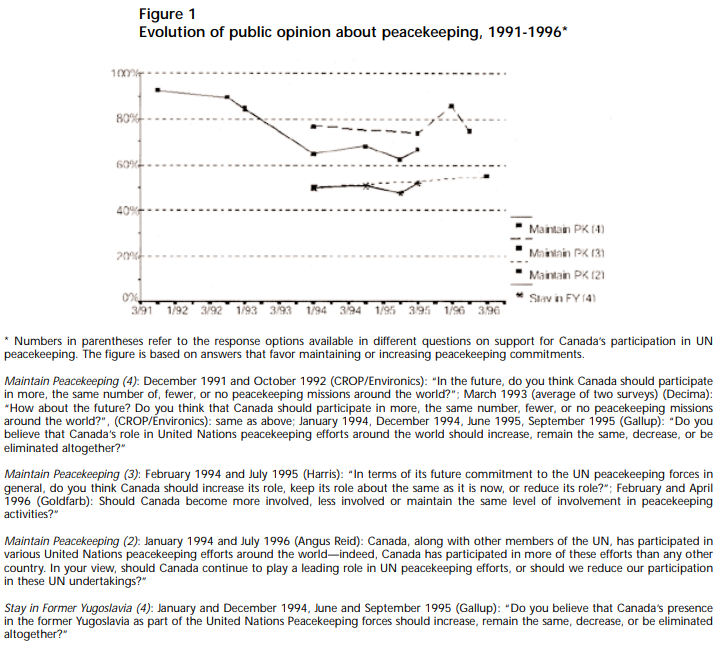

Even if the Cold War was not always easy for peacekeepers, its end signaled the start of a rollercoaster ride that would submit the public’s support for peacekeeping to a severe test. During the Gulf War in 1990-91, it was claimed that participation in a US-led operation would undermine Canada’s credibility as a peacekeeper, but this debate had little effect on the public and, as Figure 1 shows, a December 1991 survey found nearly unanimous approval for increasing (44 per cent) or maintaining (48 per cent) Canada’s contribution to UN peacekeeping. From this point on, the public attentively followed the unfolding stories of peacekeeping efforts in the former Yugoslavia, in Africa and in Haiti.

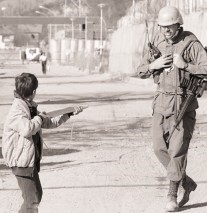

In the beginning of Canada’s involvement in the Balkans, the public was enthusiastic. A majority of Canadians, shocked by the violence in the former Yugoslavia, favored a strong Canadian presence. In fact, they showed more activism than ever before and, as the UN created new mission after new mission (14 in all between 1988 and 1993), Canada joined all but one of them. Moreover, Canadians wanted to do more.

By the end of 1993 however, many critical voices began to be heard. Chief among them was General Lewis MacKenzie, who strongly criticized the UN’s poor showing in the Bosnian quagmire. The result was that peacekeeping increasingly received a hard look from public opinion leaders and the media. In view of the UN’s failure to meet the high expectations of the international community in Bosnia, Somalia and Rwanda, observers started to ask if the benefits were worth the effort and the risk.

This crisis was occurring at a time when the Canadian military establishment was facing severe resource constraints, and Canadians began to realize that the uniqueness of their country’s role on the peacekeeping scene was dwindling. Moreover, Canada’s exclusion from the peace process in the former Yugoslavia made it all the more difficult to defend continued involvement in the region. All in all, from 1993 to 1997, Canadians’ faith in peacekeeping was submitted to severe shock treatment. How did this crisis affect the public’s support for what was increasingly perceived as the most important international role of the Canadian Armed Forces?

At a general level, support for the principle of UN activism in conflict resolution solidified through the crisis. In October 1995, Canadians told Environics that they continued to support UN peacekeeping efforts and were still willing to accept a relatively high level of risk. The most revealing time series, however, is the movement of opinion on Canada’s own commitment to UN peacekeeping missions. Surveys taken between 1991 and 1993 yielded impressive majorities in favor of increasing or maintaining Canada’s commitment, but support dropped sharply in January 1994. Can this shift be dismissed as a mood swing? In fact, this series of polling results suggests a public opinion that is far from volatile. The data suggest that there was a readjustment in the public’s views resulting from the increasing cost of Canada’s peacekeeping involvement, and that this was followed by a relative stability, or even slight improvement in all indicators of support for that involvement.

Considering the controversies that surrounded missions in Somalia throughout 1993 and in Bosnia in December 1993 and January 1994, this drop in support is understandable. Events in Bosnia, in particular, caused upset. The episode of the kidnapping and ”mock execution” of 11 Canadian soldiers by a group of Bosnian Serbs received enormous media coverage. On January 4, just days before Gallup made its survey, the new Prime Minister, Jean Chrétien, presented a confused picture of his government’s stand on Bosnia when he declared that he was seriously considering the removal of Canada’s peacekeeping troops. From that moment, peacekeeping was closely intertwined in the public’s mind with the particularly difficult Bosnian situation and with the government’s wavering. After that initial shock, however, Gallup registered little movement in the following two years, with support for involvement in Yugoslavia moving within the narrow band of 48 per cent to 52 per cent, and support for peacekeeping operations in general varying between 63 per cent and 68 per cent. In these polls, the proportion of those wishing to eliminate peacekeeping involvement altogether never exceeded 17 per cent.

Does this mean that the long-standing Canadian public support for peacekeeping involvement is starting a long-term downward slide? The results of subsequent polls suggest, to the contrary, that Canadian support for peace-keeping missions was resilient enough to weather the storm. After Ottawa’s March 1994 announcement of a six-month extension of its UN mandate in Bosnia, an Environics poll showed that 52 per cent of respondents approved of the further involvement of Canadian troops in Bosnia (while 41 per cent disapproved).

Support improved later, at the time of the Dayton accords. Although the Somalia inquiry was in full swing then and eroding some of the public’s confidence in the defense élite, 59 per cent of Canadians favored participating in IFOR. Although this level of support gives a measure of the strength of the public’s support for involvement in international peace efforts, it did not reflect blind optimism. In fact, respondents in the same survey were pessimistic—or perhaps lucid—about the prospects of lasting peace in the former Yugoslavia: 61 per cent thought it unlikely.

Since the level of risk and complexity associated with the new type of ”peacebuilding” missions is higher than it was in ”traditional” peacekeeping, it is not surprising that the public is more cautious. One cannot jump to the conclusion, however, that the public has abandoned its long-standing support for Canada’s active involvement in UN peacekeeping. Rather, a strong case can be made that the public learned something from the turbulent experiences of the 1990s.

There is little doubt that the debate on the place of peacekeeping in Canadian security policy will continue, or that public opinion will be called upon as a witness for both the prosecution and the defense. It is even more likely that participants in this debate will invoke the kinds of misconceptions about the instability and incoherence of public opinion that are so common in expert comments about foreign policy. By contrast, we observe that public opinion on peacekeeping tends to be stable over time and reacts in reasonable and predictable ways to external events.

Another test of the Canadian public’s support for military interventionism abroad came in the spring of 1999, as Canada found itself enmeshed in a shooting war against the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia over the fate of Kosovo.

As a relatively small partner in NATO, Canada was presented with a fait accompli. Since NATO is the cornerstone of Canadian security policy, outright opposition to the war was unrealistic, but, unlike some other members of the alliance, Canada chose to be an eager participant. Although its contribution to the Kosovo air war was small compared to the massive US deployment, it was substantial compared to that of other small allies.

Public opinion did not act as a constraint to action, but neither was it a driving force. Interestingly, while support for international intervention most often is driven by demonstrations of strong leadership on the part of policy makers, we do not find strong evidence that public opinion followed the leaders in this case. Why, then, did it hold firm?

Several factors suggest that public opinion about NATO’s war over Kosovo, and about Canada’s participation, could have been a great deal more skeptical. First, Canada did not make the key decisions and the feeling of being pushed around by their powerful neighbor is a historic source of irritation for Canadians. The lack of a UN mandate to legitimize the NATO strikes also might have been expected to fuel public opposition. The absence of a public debate about Canadian participation in the war, and the Liberal government’s decision not to debate the war in Parliament the day after the bombing started also generated criticism. The government held hearings and public forums later, but that seemed almost an afterthought. Finally, the conduct of the war itself gave plenty of opportunities for opponents to raise major ethical concerns.

In this context there was no guarantee that public opinion would necessarily hold firm, but it did. In early April, when it had already become evident that there would be no quick and easy resolution to the Kosovo issue, a sizable majority of the Canadian public approved both NATO’s actions and Canada’s involvement. A Compas poll showed 79 per cent of support for NATO’s actions and 72 per cent approval of Canadian involvement. As much as 57 per cent of respondents even favored sending ground troops if necessary. Similarly, an Angus Reid survey found that two-thirds of respondents approved both of NATO’s actions and Canada’s part in them. Sixty per cent approved the resort to ground forces, including Canadian soldiers, if necessary.

Even after the conflict had dragged on for several more weeks, support for the intervention remained strong. An Environics poll conducted in late May found that 57 per cent approved of Canada’s participation in the air strikes against Yugoslavia (while only 31 per cent disapproved). A sizable majority claimed to have followed the conflict attentively.

In fact, in the level of its support for the NATO intervention in Yugoslavia, the Canadian public ranked among the highest of all the NATO members, even though Canada was perhaps one of the least affected by the conflict in terms of its traditional geostrategic interests. In the Kosovo war, interests and values evidently were intertwined. For Canada, values provided the bulk of the motivation, both for the government’s policy response and for the public’s support.

As suggested above, however, public support was not a by-product of strong leadership. Canada having been called into war by virtue of its alliance obligations, its choices were more or less dictated by the internal logic of its security policy, in which in recent years humanitarian considerations have loomed large. The public came to the same conclusions on its own and gave its support, even though its leaders were severely criticized for their slowness in engaging a public debate on the intervention. In the end, the war itself was short, and its costs for Canadians were low, so there was no real need for strong leadership to retain public support. There is, of course, no guarantee that such a test will never come in the future.

To conclude, in general, we find public opinion to be more resilient in its internationalism than many commentators have noted. This was particularly true in the case of support for Canada’s participation in UN peacekeeping operations and support for joining NATO in Operation Allied Force. Of course, we do not argue that the Canadian public will cling to internationalism regardless of cost. Indeed, when survey questions highlight the costs and risks of international involvement, the public tends to drape its internationalist inclinations in considerable nuance and caution. The same, however, could be said of public opinion in any area of government activity and—more to the point–of public opinion on foreign policy before the 1990s. Whether part of the fiscal surpluses anticipated in the near future is directed towards a more convincing substantiation of Canada’s internationalist reputation will prove a crucial test of the connection between the apparent wishes of the public and the capacity of its leaders to deliver the goods.

Many commentators have also observed that the public tends to be increasingly wary of its political leaders and less deferential to their authority. From this observation, many infer that an internationalist foreign policy is more difficult to sustain. In general, however, when political leaders demonstrate conviction in pursuing their policy objectives, and when they take the time to explain why the difficult choices they make are necessary to pursue the values and principles shared by most of their constituents, public opinion rarely poses itself as an obstacle to a constructive foreign policy. When, by contrast, leaders waver on their commitments or compromise on the principles that underpin the citizens’ belief in internationalism, one should not be surprised if a warier and less deferential public reserves its judgment, or even withdraws its support for their international actions.

In sum, we do not deny that there have been signs of retrenchment in Canadian internationalism. We agree that this trend can only partly be explained by changes in the international context, and that it also has domestic causes. Still, our reading of the available evidence leads us to conclude that, although public opinion is a convenient scapegoat for the apparent lack of political will to support a constructive internationalist policy, the real obstacles lie elsewhere.

When the public is treated as a legitimate partner in the elaboration and conduct of foreign policy, there is no reason to assume that it will pose itself as an obstacle—even when choices become difficult and costly. The silent internationalist majority is entitled to expect political skill and courage from its leaders in defense of their values. If the public does not insist on being treated as a full partner in the foreign-policy process, however, it is more likely to remain a scapegoat.

Photo: Shutterstock