A host of enthusiasts, from the early pioneers of Wired Magazine and the Electronic Frontier Foundation to the newest innovators of City Protocol (the new web-based global cities network in Barcelona), are persuaded that digitally linked, so-called smart cities are on the cutting edge of urban innovation. In keeping with the soft technological determinism of Google founder Eric Schmidt and his ideas director Jared Cohen (a political scientist), many observers are sure that “the new digital age” is “reshaping the future of people, nations and business.” Integral to this idea of a digital world is the notion of smart cities, which are presumed to have the potential to give new meaning to the idea of digital rights and to promote intercity cooperation. Do they?

Let me pose the question this way: Can the ubiquitous technology that everywhere promises digital Nirvana actually further the goal of global networking and the governance of mayors? Or is it burdened by too many of the weaknesses that have stymied technocrats, too many of the failed promises that have repeatedly disappointed the techno-zealots yearning for transfiguration by engineering? As democrats and advocates of global urban governance, we need to have convincing answers to such questions in order to assess the possibilities of smart cities. Should we heed the giddy champions of technology and raise our expectations, or allow a prudent cyber skepticism to dampen them?

Smart cities are simply tech-savvy towns that utilize digital innovation to do their business. But smart cities are also self-consciously interdependent cities that use technology to enhance communication, hoping to make smart cities wireless nodes in a global network and reinforce their natural inclination to connectivity and collaboration. For civic entities defined as much by interaction, creativity, and innovation as by place, maps, and topographical boundaries, the cloud isn’t a bad place to be. By digitally escaping the limits of space and time, cities embrace and realize — they literally virtualize — the metaphors and constructs that define them.

The new global space of flows is profoundly urban. Increasingly, cities are depending on technology as the key to sustainability, economic vitality, and commercial and cultural exchange. They hope to be able to turn the abstract notion of flows into concrete interconnectivity. To be sure, cities know technology per se is only a means, and as such, carries its own baggage. Yet cyber-zealotry is infectious. As one proponent of smart cities has noted, “we can collect and access data now from an astonishing variety of sources: there are 30 billion RFID tags [the new tech barcodes] embedded into our world . . . we have 1 billion cell phones with cameras able to capture and share images and events; and everything from domestic appliances to vehicles to buildings is increasingly able to monitor its location, condition and performance and communicate that information to the outside world.” Cities have always been interdependent: the digital revolution has simply rendered that interdependence palpable — putatively both efficient and concrete. Maybe.

A recent example of how seductively the web and the innovative companies attending its evolution can claim to facilitate urban connectivity is City Protocol, a new website project and cities association promising a new set of virally shared best practices for its members. Fashioned initially through a partnership between the city of Barcelona and Cisco Systems (whose chief globalization officer, Wim Elfrink, is an urban governance innovator), it currently includes thirty cities working with key universities, tech companies, and civic organizations [Surrey, B.C. is the only Canadian signatory]. Its aim is “to define a global, cooperative framework among cities, industries and institutions with the goal to address urban challenges in a systemic way in areas such as sustainability, self-sufficiency, quality of life, competitiveness and citizen participation.” It focuses on the role of technology in urban innovation and aspires to “platform integration and technology and solutions development.”

At present, City Protocol is in the early stage of development, but though it offers proof that technology is no longer just a mote in the eye of urban innovators or the subject of speculative reflection and research at think tanks like the Intelligent Community Forum, it has yet to prove whether it actually can produce results for cities aspiring to work together. Putting the enticing verbiage aside, the question is whether putting best practices and innovative policy initiatives on a web feed that goes directly to member cities actually alters the urban landscape. Will ideas spread more quickly? The bike-share program so popular in cities today actually caught fire initially, at least in part, through tourism and travel, with a Chicago city councilman seeing something exciting in a Latin American city he was visiting. Tradesmen and commercial travelers have always been “viral” carriers of ideas, even when they traveled by camel.

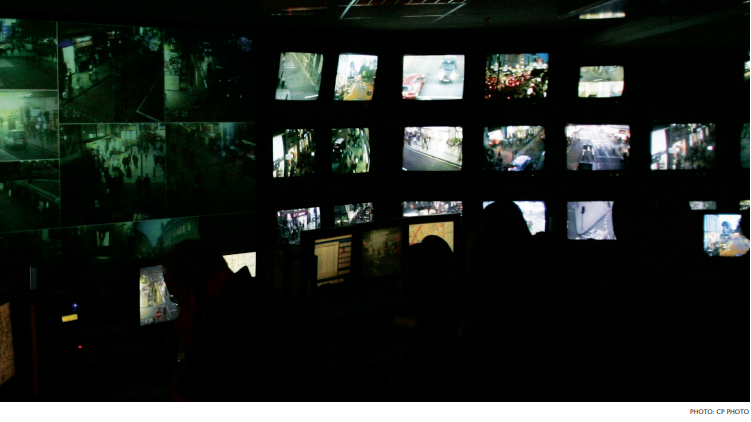

The question we need to ask today is whether efficiency in communication and information access will improve urban services (that is the promise of digital health care record-keeping and metro schedule screens) or merely centralize surveillance and control and infringe privacy. Thousands of centrally monitored urban video cams (of the kind London now deploys) will no doubt be regarded by police officials as a boon to crime prevention, and London is being imitated in many other cities today, including New York. In Boston, it was these street cams that helped identify the Marathon bombers.

But will citizens concerned with rights see the London practice more as something resembling Foucault’s Panopticon, sweeping away the last vestiges of privacy with ubiquitous surveillance? Or will the yearning for absolute security bury even modest notions of rights?

I will not track here the new literature that toys with distinctions between smart cities and so-called cyber cities or digital or intelligent cities, though it must be noted that the plethora of hip brand names suggests that the many new public-private partnerships that are emerging around technology and the city are being rather heavily hyped. The reality is more ambiguous and complex. The digital world encompasses thousands of cable and satellite broadcast channels, 600 million Internet sites, almost a billion Facebook users, and perhaps 70 million bloggers (with more than 50,000 new ones appearing every day), along with storage for all photos, files, programs and all that “big data” in a virtual cloud no longer safely inscribed on our own hard drives. Almost all of these public technologies are privately owned by quasi monopolies. Because the federal Telecommunications Act of 1996 passed in the Clinton years allowed the privatization of all such new media (spectrum abundance supposedly eliminating monopoly and thus the need to regulate media), cities cannot become smart without forging public-private partnerships.

Many of the technologies were developed for commercial (for-profit-) purposes: multiplying applications can locate pizza parlors and runaway pets or find open parking spaces and pay parking fines. But when the chips and GPS applications are adopted by the state, they let every cop and every political snoop know exactly where dissidents and “subversives” are — and permit the location and rounding up of lawful demonstrators an oppressive regime may wish to shut down. So-called Big Data inundates us with information more useful to marketers or security officials than to policy makers trying to make prudent judgments and looking for knowledge and wisdom. Knowing where available parking places are via sensors is useful to urban drivers, but may increase automobile use when the better part of environmental wisdom is to limit driving altogether.

I will argue, then, that technology can both facilitate and compromise what cities are doing to enhance their interdependence, but way too often, those employing it don’t know the difference. Nor do they necessarily grasp what it means to partner with powerful private-sector corporations. Corporations have a fiscal obligation to their shareholders to make money off their urban technology, but cities need to be aware that the smart-city portion of the business sector was estimated to have earned as much as $34 billion (USD) in 2012 and has been projected to be able to earn $57 billion by 2015. Tech companies do not embrace smart-city initiatives disinterestedly in the name of public goods, though that certainly does not mean their partnerships cannot also serve such goals.

For all the promise and all the promising, there is as yet no cyber commons, no digital public square, Google’s experiment in Hangouts notwithstanding. Innovations like participatory budgeting, though spread by the web, are rooted not in high tech but in traditional citizens’ assemblies and boards or participatory councils exercising meaningful budget control through co-planning processes. Such experiments may have resulted in an “empowerment of civil society and, most notably, of the working class,” but these results are unrelated to technology.

Technological implementation of participatory ideals among cities remains aspiration. And for good reason. It is generally acknowledged that online communities are rarely invented on line but are initiated in the real world and then pursued and sustained virtually. James Crabtree, an editor at openDemocracy.net, has prudently noted that “if we are not interested in politics, electronic politics will not help.”

And if politicians remain cynical about democracy, we might add, they will use new technology only to get elected. Even a techno-zealot like Gavin Newsom admits politicians “love to use social media — but only for getting people involved in campaigns or getting into their wallets.” Yes, he confesses, “we build fancy Web sites; we ramp up our tweeting and texting and engaging and mashing up; we host online town halls. And then, once we get elected, we just shut all that off and go away — until the next campaign season rolls around. No wonder people feel disconnected.”

Crabtree still would like to see the music file-sharing techniques (peer-to-peer or P2P technology) behind -Napster applied to politics, and he asks the question: “Napster is to music as what is to politics?” By analogy there should be a “Citizster, or Polster.” Yet it is not so much the application that is missing as the civic desire to develop and support it. If we are not interested in politics, e-politics won’t help. It is for this reason that a true intercity civic commons online — a “citizster” civic file-sharing program — will likely have to follow rather than precede a civic campaign to establish intercity governance and the establishment of a parliament of mayors. Indeed, the fashioning of such a digital commons might even become a high purpose of a global cities secretariat.

The virtual always mimics the real. Citizens do not need a gateway drug for civic engagement, they need to take their citizenship cold-sober seriously. If they do so, technology can certainly help them engage across time and space, and companies like Cisco and Ericsson can then become their (our) allies. Google might even be able to turn its Hangouts into a true digital commons. Where cities go and citizens lead, there technology can follow, reinforcing and augmenting their progress in significant ways. But as in the past, truly smart cities will rely first not on instrumental technology but on the primary intelligence of citizens and the judgment of mayors in solving the (not just urban) problems of an interdependent world.

Excerpted with permission from If Mayors Ruled the World: Dysfunctional Nations, Rising Cities, by Benjamin R. Barber, forthcoming, November 4, 2013. (©Yale University Press).

Photo: Shutterstock by metamorworks