In the early months of the first George W. Bush administration, when I worked intensively on energy and climate change issues at the US Embassy in Ottawa, our team told the White House that waiting for the US government to take a position on carbon emissions was “torture” for Canadian policy-makers. Canada could not take serious steps on carbon and climate until it knew where America stood, we told the administration. As the smaller partner in an integrated industrial economy, Canada’s stance simply had to take America’s into account.

There would be no quick end to the torture. President Bush’s response to the climate issue was essentially that the problem was not amenable to quick fixes and that major long-term investments in energy technologies likely represented the most promising hope for a solution. Reasonable enough. But that approach did not satisfy the sense of urgency that pervaded much of the international community, nor its longing for leadership as confidence in the Kyoto Protocol targets weakened.

Over a decade later, Canadian policy-makers, now free of Kyoto and with a Democrat in the White House, continue to defer to US leadership to shape a continental policy direction on carbon and climate.

It has taken until the second term and a failed attempt at a cap-and-trade bill, but President Barack Obama has finally articulated a way forward, laying out a series of measures in a speech at Georgetown University on June 25 that was billed and seen as a major address. And indeed the speech was important, though less for the initiatives it proposed than for what it said between the lines about the direction of American energy policy for years to come.

This is not meant to be unkind. The President and his team are presumably conscientious people trying to tackle a serious global problem as best they can, given the political circumstances of a gridlocked Congress and a slow, mostly jobless economic recovery. They are advocating steps that are realistic and helpful.

But their action plan will not produce a turnaround for America’s carbon emissions problem, let alone the world’s. Here’s why:

- It’s in attainable pieces: Neither of the comprehensive approaches to climate management — a carbon tax or a cap-and-trade regime — was mentioned, except obliquely as something the President “still wants to see happen.” This implies that there will be no such approach in the United States at least for the next few years. And if this progressive, activist president, recently re-elected to his second term and seeking a historic legacy, did not try such an approach, it is a long shot that any successor will either.

- It’s domestically focused: President Obama’s Climate Action Plan is largely a domestic program, with a modest international component of which the most specific parts are export-promoting (expressed as “negotiations toward global free trade in environmental goods and services, including clean energy technology “). The Georgetown speech put no new momentum — beyond a pledge to “redouble our efforts” — behind the quest for a new global regime that will improve on the flaws of Kyoto. Instead, America will “lead by example” in slowing the growth of its carbon emissions. While the President is right that “no nation can solve this challenge alone,” the plan’s international dimension is consistent with the lower world-transformative ambitions of post-Bush America.

- It’s accommodating: Substantial parts of the plan deal with managing the impacts of climate change through such measures as drought resistance, flood risk reduction, hospital resiliency and stronger local-level emergency preparedness. This is a shift from prevention to adaptation; climate change is seen less as a future threat to be averted, and more as a fait accompli.

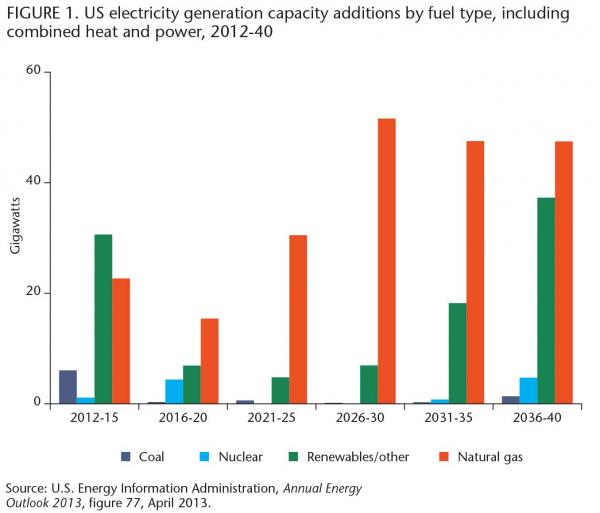

- It uses a familiar policy tool kit: Pollution regulations for power plants, renewable energy, building and appliance efficiency, vehicle fuel economy, investments in energy technology — these are worthy but not groundbreaking stuff. While each can make a modest contribution to slowing the growth of carbon in our atmosphere, such measures could have come from any administration. Obama deserves extra credit for ramping up investment in next-generation nuclear power, but this, too, makes enough sense that any president might have done it.

While Obama’s response to the carbon challenge is reasonable enough and quite practical, we are now three presidential terms down the road since we first looked to the George W. Bush administration to point the way. North America in 2013 still has no general carbon tax and no plan for a broad cap-and-trade regime, while the number of miles driven by gasoline engines and flown in fossil-fuelled jets keeps expanding. To put it plainly, the White House might have called this the “Plan to Stick with Hydrocarbons for Now and Accept a Hotter, Stormier Planet. “As the President said: “The hard truth is…the planet will slowly keep warming for some time to come. The seas will slowly keep rising; the storms will get more severe. It’s going to take time for emissions to stabilize.”

Emissions — let alone atmospheric concentrations.

Given that this is more or less a plan to stay on fossil fuels for at least a few decades, there was another important and remarkable element to the speech: an absence of any reference to the risks of dependency and price. Awareness of these risks has been a part of the American oil conversation at least since the Arab oil embargo that followed the war with Israel in 1973. Had the President’s speech been delivered in an earlier decade, it would certainly have recognized the worries of overreliance on oil and of major oil price rises, whether the chief bogeyman was OPEC, the concept of “peak oil, “fear of conflict in the oil-soaked Persian Gulf or warnings against “funding America’s enemies” with petrodollars.

But the Georgetown speech makes no mention of these long-standing features of America’s thinking about energy.

Their action plan will not produce a turnaround for America’s carbon emissions problem, let alone the world’s.

What has changed in America’s attitude toward hydrocarbons? Why has there been a discounting of the geopolitical risks arising from dependency on Middle East oil states and potentially abrupt, economically painful oil and gas price increases?

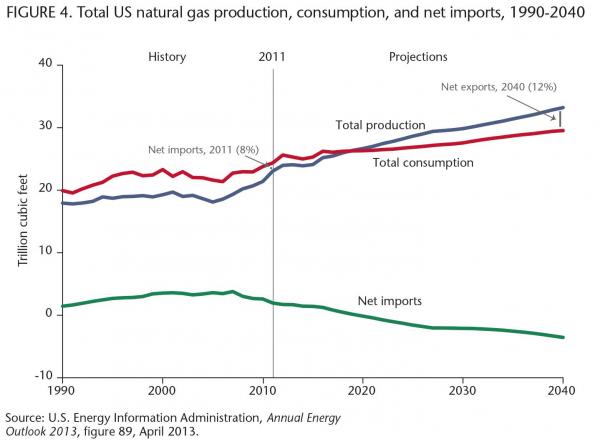

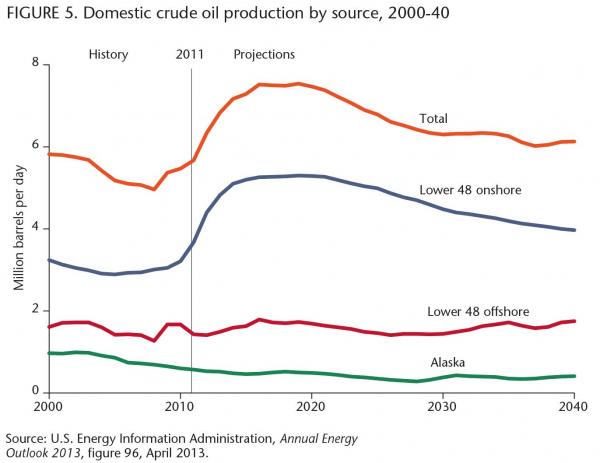

The answer lies with the rock-fracturing (“fracking”) revolution that has transformed the fossil fuel industry in the past decade, allowing Americans to extract far more oil and gas from their existing deposits. As Obama’s speech repeatedly and proudly noted, America has rebounded as an oil- and gas-producing economy. Domestic supplies of these fuels have increased, while prices have remained reasonably stable or, in the case of natural gas, historically low. Oil, gas and their derivatives are once again seen as American products, and the growing demand for them is seen as good for American business.

Listen to the President: “For the first time in 18 years, America is poised to produce more of our own oil than we buy from other nations, “ he said. “And today, we produce more natural gas than anybody else. So we’re producing energy. And these advances have grown our economy, they’ve created new jobs, they can’t be shipped overseas — and, by the way, they’ve also helped drive our carbon pollution to its lowest levels in nearly 20 years. Since 2006, no country on Earth has reduced its total carbon pollution by as much as the United States of America.” Progress, the President is saying, is no longer represented by getting off of fossil fuels, but by shifting from one to the other and producing more of them at home.

This celebration of America’s hydrocarbon production is the really notable feature of the Georgetown speech. Washington has apparently gotten beyond four decades of worry about dependency on fossil fuels, the troublesome places they come from and the economic risks that dependency breeds. Indeed, the President has unveiled a Climate Action Plan that continues more or less reliance on them for decades to come.

Building oil pipelines southward from Canada is no longer unambiguously good for US business.

There are two problems with this stance. The first, obviously, is that it accepts the continuation of higher atmospheric greenhouse gas concentrations and (presumably) a hotter and stormier planet. Even the modest international component of the Obama plan touts the switch to natural gas. “We’re going to partner with our private sector to apply private sector technological know-how in countries that transition to natural gas,” he said. “We’ve mobilized billions of dollars in private capital for clean energy projects around the world.” So not just for America, but globally, “clean energy” means gas.

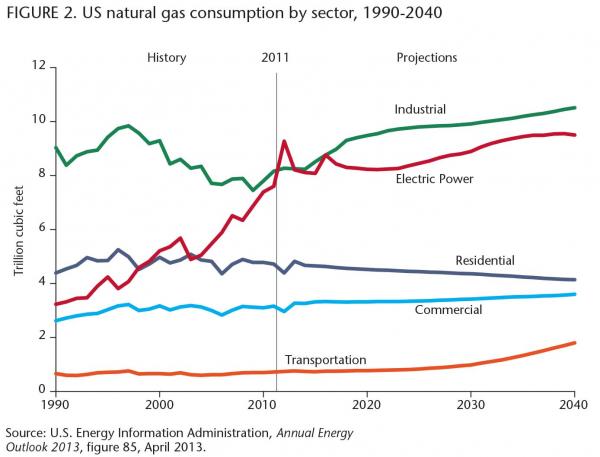

Now the second problem emerges. Low-priced gas over the past decade has already been tilting investment in energy infrastructure toward gas pipes, rather than lower-carbon alternatives. Unlike electric power — whose grid carries electrons from any source — gas is collected and delivered through a single-fuel pipeline grid that serves only gas. North Americans are, and have been for more than a decade, locking into a single, moderately dirty, high-greenhouse-gas-emitting fuel. This is happening through more use of natural gas for everything from building heat to industrial processing to power generation to trucking.

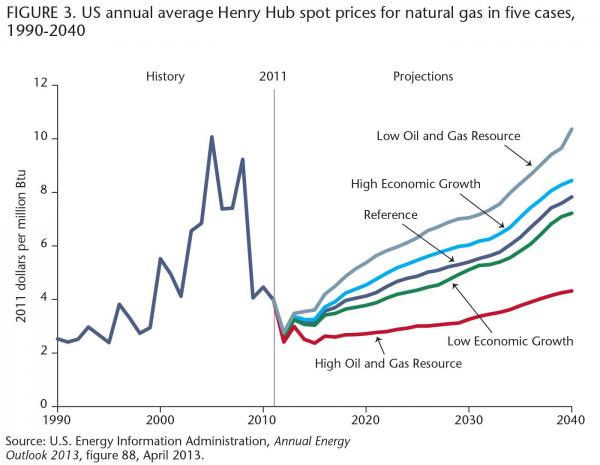

Underlying this shift toward natural gas, apart from low prices and the continuing whitewash that gas is “clean” when really it’s an improvement only on oil and coal, has been lower price volatility. In recent years, thanks to fracking, gas has been not only cheap but unusually stable in price.

Carbon is just one of two major problems that come with building an economy that runs on much more natural gas. The other is commodity price risk — our familiar companion from the 1970s. The price of natural gas can fluctuate sharply and has done so historically — though never before when we were this reliant on it.

The Georgetown speech’s clear subtext that gas is good essentially approves the building-in of fossil fuel price risk to our energy systems, and authorizes more of it. In Obama’s Climate Action Plan, this fuel “is creating jobs. It’s lowering many families’ heat and power bills. And it’s the transition fuel that can power our economy with less carbon pollution.” We might have said the same of crude oil at one time.

We are all betting, and are going to continue to bet, not only that natural gas has become cheap but that it’s become reliably cheap. Even sharp volatility around current average price levels would come as a rude surprise.

And oil, while neither particularly cheap nor clean, is coming increasingly from America’s own wells and properties. Alert Canadian readers will have noticed that building oil pipelines southward from Canada — warmly encouraged as a step toward energy security by the Bush administration — is no longer unambiguously good for US business. Indeed such supplies merely threaten to cool the boom in US oil and gas development. This boom is now part of the “national interest” that the President’s speech said the Keystone pipeline must align with.

No wonder the Obama team is worrying less than it used to about the price risk that’s built into North America’s fossil fuel reliance. American business is increasingly a beneficiary of our buying and using hydrocarbons.

So what does this Climate Action Plan really mean for Canadian energy and climate policy-makers?

Forget taxing carbon, at least for now. No president will likely take this on anytime soon.

If you still hope to mitigate greenhouse gas emissions, continue to pin your hopes on long-run investments in new energy technologies.

Lock into using hydrocarbons. These days, enough of them come from North American deposits that we won’t fret about price spikes or continental energy security.

Oh and conserve water, because we should get ready for more floods, droughts, storms and fires.