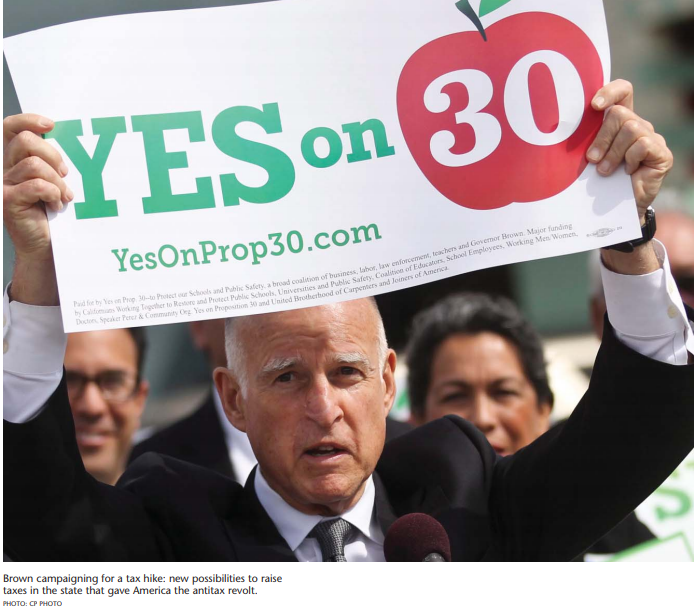

President Barack Obama may have carried California by a whopping 20 percentage points in November, but he wasn’t the only election night winner in America’s largest state. Democratic Governor Jerry Brown had every right to be just as jubilant. Brown’s Proposition 30, a statewide initiative to raise taxes by roughly $6 billion a year, pulled ahead early in the evening and went on to win with 55 percent of the vote.

The measure had become the centrepiece of Brown’s governorship, and even opposition Republicans acknowledged it was a coup. Jim Brulte, who once led Republican forces in the California state legislature and who is eyeing a comeback as chair of the party, told reporters, “It’s a huge victory — underline huge — for Jerry Brown.” Brulte was undoubtedly correct, but the tale of California’s great tax increase of 2012 may serve as not only a sign of the governor’s electoral craftiness, but also a template for politicians everywhere looking to sustain critical public programs by overcoming entrenched opposition to new revenue.

California’s tax aversion runs deep, and it is a history that Brown knows personally. In the 1970s, he was the boy wonder of American politics — the son of a California governor, he followed in his father’s footsteps when he was only 36. His first run for president, a surprisingly strong bid in 1976, came when he was not yet 40. But a huge run-up in California real estate prices was unsettling the governor’s constituents. As assessments went up, so did property tax bills, in some cases at shocking speed.

The result was Proposition 13, a 1978 measure to cap property tax rates at 1 percent of assessed value and limit the increase in assessments to just 2 percent a year. In short order, Proposition 13 spawned a slew of imitators in other states and ushered in a long era of antitax rhetoric in the Republican Party. The man who preceded Brown as California governor, Ronald Reagan, rode the wave all the way to the White House.

Within the state, another provision of Proposition 13 may have been just as important. In addition to limiting property taxes, the initiative mandated that bills increasing any kind of taxes needed a two-thirds vote to pass the Legislature. In practice, of course, this granted veto power over taxes to one-third of the Legislature, and minority Republicans used it vigorously. California’s antitax reputation was only strengthened in 2003 when voters recalled Governor Gray Davis, who had allowed motor vehicle registration fees — derided as the “car tax” — to go back up after a temporary cut, and again in 2006, when Democratic gubernatorial nominee Phil Angelides proposed a tax increase on the wealthy, only to be roundly rejected by the voters.

When Brown decided to seek a third term as governor in 2010 — a full 28 years after he left the office at the end of his second — he faced not only this history of fiscal stinginess but also huge budget deficits projected to run for years. California had long relied for the bulk of its revenue on income taxes paid by the wealthy, which vary sharply with the fate of the economy and the stock market. Personal income taxes account for about two-thirds of the state’s General Fund, and almost 87 percent of those taxes are paid by the top 20 percent of earners (who collectively earn, it should be noted, 63 percent of the state’s total income).

That system worked well during the dot-com boom of the late 1990s, when Silicon Valley was minting billionaires and the state budget reaped the rewards. But when the boom went bust, tax collections plummeted. At the start of the recent Great Recession, the state’s General Fund revenue fell by almost 20 percent in a single year, from US$103 billion to US$83 billion. Gaping budget deficits emerged every year, and were resolved only through harsh budget cuts, phony accounting gimmicks or, more typically, both. By the time Brown was inaugurated for his third term in January 2011, the state faced a US$25.4 billion gap for the next 18 months, with similar shortfalls projected as far as the eye could see. There was plenty of talk that the state’s finances were permanently ruined.

Brown wanted to both cut spending and raise taxes. Aware of profound voter cynicism about the ultimate use of public money, he had vowed in his initial campaign announcement that any tax increase would come only with the approval of voters. In office he stuck to the pledge, even when the Legislature’s Republicans refused to refer the tax measure to the ballot. (Like a tax increase, a referral to the ballot requires a two-thirds vote, and Republicans still held enough seats to effectively veto the proposal.) Stymied, Brown decided that in 2012 he would simply bypass the Legislature and use California’s initiative process that sends policy decisions directly to voters. His supporters gathered enough voter signatures to put the tax increase, known as Proposition 30, on the ballot for the November election.

“Prop. 30” called for temporary increases in both the income tax and the sales tax. The income tax increase, which will last for seven years, will affect only those making at least US$250,000 a year in taxable income, US$500,000 for a couple filing jointly. The new rates will add an additional 1 to 3 percent per year, depending on income, onto the state’s existing top rate of 9.3 percent, or 10.3 percent for those making at least US$1 million a year. The sales tax increase, which will last only four years, will increase the levy by one-quarter cent for every dollar in sales, to 7.5 percent (cities and counties can, with voter approval, boost the rate even higher on a local basis).

As the campaign began last summer, there was plenty of skepticism about Proposition 30’s chances. In June, the Field Poll, California’s most respected independent polling outfit, found Brown’s approval rating had fallen to 43 percent, and the tax measure itself was polling only at 52 percent, with 35 opposed and the rest undecided. Conventional wisdom in the state holds that propositions shed support as election day approaches, as confused or uncertain voters move into the “no” column and stick with the status quo.

But the governor held some crucial cards.

For one thing, Brown and his Democratic allies in the Legislature embedded the tax increase into the state budget. California begins its fiscal year July 1, and this year’s spending plan assumed passage of Proposition 30 — even though the measure would not actually go before voters for another four months. The budget included $6 billion in predetermined cuts that would kick in automatically if voters rejected the governor’s proposal. The vast bulk of those cuts, US$5.4 billion, was aimed at public education, far and away the largest portion of the state budget.

Building the new taxes into the budget was politically deft, because it allowed the governor to say that if the measure failed, schools would unavoidably face extraordinary cutbacks, perhaps even shaving weeks off the academic year. Critics from the right called it a scare tactic, and policy wonks noted there was no guaranteeing the added tax revenue would be spent on education in future years. But the direct nexus — vote “aye” or see your kid’s school funding slashed to pieces — was a powerful argument to voters.

The governor’s proposal was also brilliantly designed in that while most of the votes would come from average folks, most of the money would come from the wealthy. Indeed, except for the relatively small increase in the sales tax, the average Californian will never feel the impact of Proposition 30 at all. The state’s much respected Legislative Analyst’s Office estimated that the new income tax rates will apply only to the top 1 percent of California filers.

How important was that threat to the measure’s passage? Perhaps the best indicator is the fate of a rival tax measure that was also on the November ballot. Sponsored by wealthy attorney Molly Munger, the alternative measure would have raised more money for more years — roughly US$10 billion a year for 12 years — and thus in a certain sense should have been more appealing to voters wanting to fund public education.

But that measure would have raised income taxes for almost everyone, all the way down to those with an annual taxable income of just US$7,316. In other words, unlike Brown, Munger was asking average voters to raise their own income tax bill substantially. The voters’ verdict? The Munger measure got less than 29 percent of the vote.

On policy grounds, there are some serious questions about the governor’s approach, since it’s reliance on high-income earners will only worsen the state’s wild swings in revenue. But it seems clear that in political terms, Brown was far sharper than Munger. US Senator Russell Long, a wily Louisiana Democrat from the old school, used to say that the average American’s preference for tax policy was, “Don’t tax you, don’t tax me, tax the fellow behind the tree.” The California governor offered voters the chance to do exactly that — and voters liked it.

A final and perhaps the most important lesson from the California experience: The conventional wisdom about taxes may be more conventional than wise. It’s true that Californians launched the Great American Tax Revolt with Proposition 13 three decades ago, and it’s true that in the years since then, they often rejected other proposed tax increases. But the antitax case was never quite as airtight as some would have claimed.

Perhaps most instructive was a 2004 ballot measure sponsored by the president of the state Senate, Darrell Steinberg. Like Proposition 30, Steinberg’s measure raised income tax rates only on the rich, then used the money to fund politically popular programs (in that case, treatment of mental illness). It passed, though not quite with the same margin as Proposition 30. More recently, a couple of months after Brown took office in 2011, a joint survey by the Field Poll and the University of California’s Institute of Governmental Studies found that a small majority of voters — 52 percent — favoured addressing the state’s deficit through an equal mix of spending cuts and tax increases. Less than a third favoured solving the problem only through spending cuts. The lesson may be that antitax rhetoric, while passionate, does not always carry the weight of a majority.

California likes to think of itself as a nation-state. That reflects a touch of ego, but also of reality. With 37 million people and the ninth-largest economy in the world, America’s mega-state has the heft of a middle-sized country. It also likes to think of itself as an exporter of trends, either to the rest of America or to the rest of the world, or to both. Think of the digital revolution, for example. Politically, it may be that no California product has been more popular than antagonism to taxes. Some Californians look at Proposition 13 and its legacy with pride, others with shame, but no one doubts that the state played a critical role in moving the dialogue of politics to the right, at least when it comes to taxes.

Given that history, it’s worth pondering the lessons of Jerry Brown’s accomplishment. He built a plausible case that new taxes were the only salvation for the state’s most politically popular program: education. He laid out specific cuts that would happen — automatically — if the taxes were rejected. And he gave average voters the chance to foist most of the bill onto someone else. It may not have been pretty, but it was an effective way to strike back at the no-new-taxes dogma that has dominated much of the American political discourse for the last three decades.

Photo: David Peterlin / Shutterstock