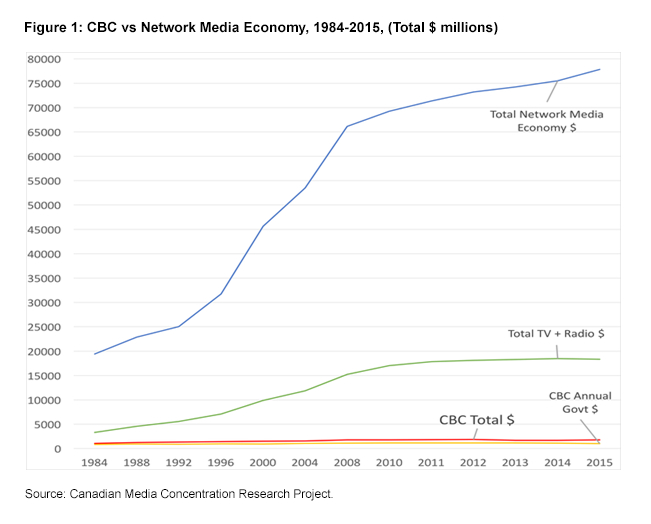

Last weekend, I participated in a debate at the Manning Centre’s annual conference entitled “Is it time to pull the plug on the CBC?” I was arguing on the “no” side. My first argument was that the CBC has shrunk greatly over time against the backdrop of a vastly larger and ever more Internet- and mobile-centric media economy, as Figure 1 below illustrates. (A “network media economy” includes a dozen or so of the largest sectors of the telecommunications, Internet and media industries, including mobile wireless and wireline telecoms services Internet service providers, cable, satellite, broadcast, specialty, pay and Internet-based TV services, radio, newspapers; magazines, music and Internet advertising.)

Over the past three decades, the place of the CBC within the media universe has been eclipsed as wholly new media have been added to it: e.g. mobile phones, broadband internet access, pay TV, OTT, online gaming, social media and search engines. In this context, carriage (or connectivity and bandwidth) is king, not content.

The size of the network media economy quadrupled from $19 billion in 1984 to $75 billion today. In general, and contrary to popular belief, Canada’s media economy is not small but one of the twelve biggest in the world.

Therefore, mobile phone rates, data caps, broadband access, fibre-to-the-doorstep, and common carriage are now at least as important as the CBC, both in terms of journalism and to most Canadians in personal terms (e.g. keeping in touch with loved ones from a distance), social terms (ie. access to knowledge, entertainment, opportunities, public services) and money terms (Canadians spend $5 on bandwidth for every $1 on media content). Excessive worrying about the CBC obscures these realities.

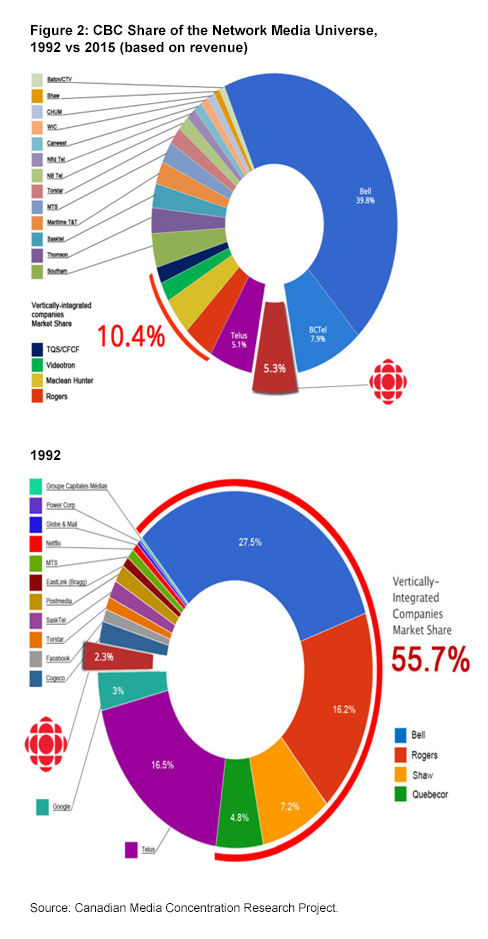

The Canadian media economy has not only become bigger and more complex but more concentrated (but with crucial exceptions, such as Internet news, radio and magazines). Figure 2 below shows how the CBC’s place within the Canadian media economy shrunk between 1992 and 2015.

The upshot of these trends is that the CBC is now dwarfed in the media world. It’s share of the total media economy dropped from 5% in 1980s and early 1990s to less than half that amount today. Stripping out telecoms from the picture does not diminish the point.

Based on revenues in Canada, Google is now bigger than the CBC, while Facebook is about half its size.

What also stands out is the extent to which a handful of companies stand at the apex of the Internet and media landscape: Bell, Rogers, Telus, Shaw, and Quebecor. Bell dominates with nearly 30% of all revenue, while the big five telecom companies account for just under three-quarters of all revenue – up from 64% in 2000.

The “Big 5’s” share of the total TV market has grown from 54% in 2008 to nearly 80% in 2015. This combination of carriage and content is called vertical integration and Canada has some of the highest levels of vertical integration in the world. This is not a good thing because:

- The telcos want to act as gatekeepers (publishers) to the Internet rather than as gateways (common carriers). CBC has been excluded from Videotron’s Unlimited Music offering where wireless subscribers use a selected catalogue of streaming music services without them counting against your monthly data caps, for example. Indeed, all telcos would like to do this. Bell’s Mobile TV offering tried to do much the same before being slapped down by the CRTC and the Federal Court of Appeals;

- Telcos’ content holdings in TV, radio, online and print are trinkets on their vast corporate edifices but they don’t care much about such things other than that they hope this “content” stuff will help them sell mobile phone and internet subscriptions – the real engines and profit centres of their operations;

- Signing up for mobile wireless and broadband internet services in Canada is expensive relative to most EU and OECD countries, as is the price of data. Data caps are also used widely and set at low levels after which punishing ‘overage charges’ kick in.

- As a result of high prices, markets for fibre-based Internet access are underdeveloped while mobile wireless and broadband internet uptake is lower than it could be;

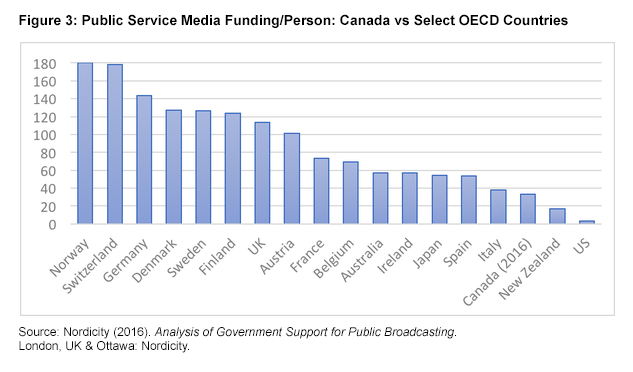

Instead of constantly railing against the CBC, these issues of concentration should be higher on our list of priorities. It’s also worth noting that the CBC’s funding levels are less than half the OECD average for public service media.

Despite all this, however, the CBC still does some things remarkably well.

It invests in original journalism and Canadian content. While the CBC accounts for just a fifth of all TV and radio revenue, it provides a third of the investment in original TV/radio journalism and a quarter of the spending on TV and radio content production. It also maintains nine international news bureaus while the private sector has cut them to the bone.

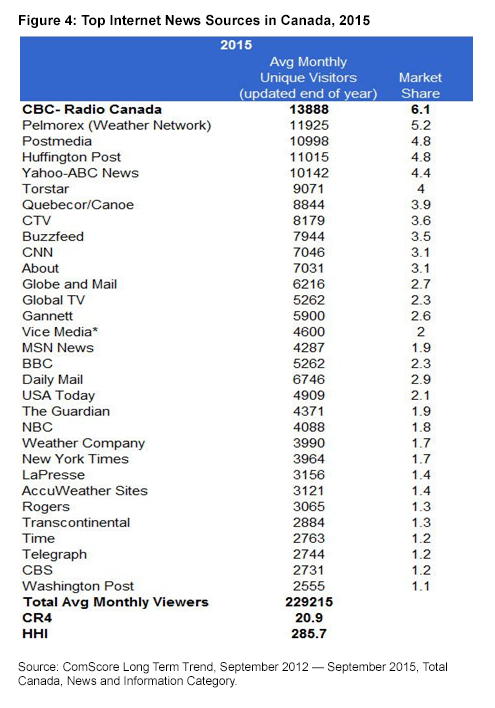

Meanwhile, CBC TV’s audience has declined but it still garners 10% of the audience share. CBC radio services are much loved with a national audience share of roughly 20%, and its streaming music services are also popular. And the CBC is the number one online news source for Canadians, as Figure 4 shows.

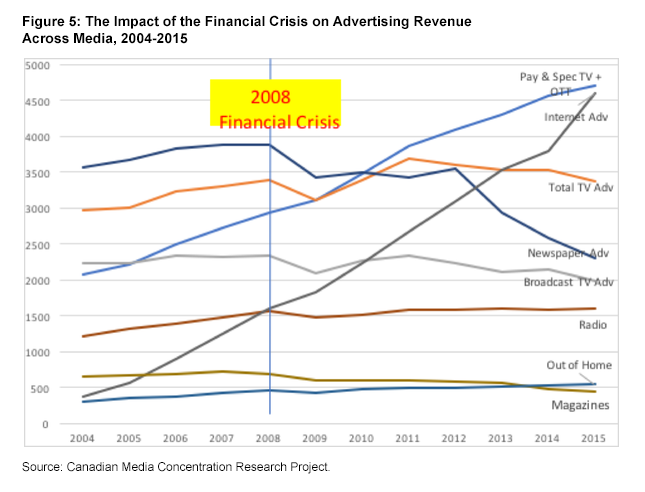

And we cannot ignore the financial difficulties the news media are facing. The economic base of the media is no longer advertising but subscription fees by a 5:1 ratio.

The public has never paid the full cost of general news services. Consequently, journalism has always been subsidized by advertising, rich patrons, propaganda in authoritarian states, or the public purse in democratic countries. As the bottom of the advertising subsidy drops out, what kind of subsidy will rush in to fill the void: (1) rich sponsors; (2) propaganda (“fake news”); or (3) the public purse?

In short, the market cannot fully support the general kind of journalism that people want and democracy needs. This is not to denigrate the market, but recognize its limits. So, what should we do?

First, realize that the CBC is a dwarf among giants. Second, clarify that its mandate includes dissemination of content on all digital media platforms. Third, advertising on the CBC should be eliminated, while its budget should be more than doubled to bring it into line with the average of the OECD countries. Fourth, to shield the CBC from political influence, five- or ten-year budget cycles should be adopted. The appointment of its president and board should be made more independent from the government of the day. Fifth, the anti-CBC hyperbole in the commercial press and in certain political quarters also needs to be dialed down. And finally, regulators need to deal squarely with the realities of the media marketplace in Canada, namely that concentration levels are high, and vertical integration levels sky high and these realities are fundamentally shaping the terrain in which our communications and media environment are unfolding.

Photo: Piotr Adamowicz/Shutterstock.com

Do you have something to say about the article you just read? Be part of the Policy Options discussion, and send in your own submission. Here is a link on how to do it. | Souhaitez-vous réagir à cet article ? Joignez-vous aux débats d’Options politiques et soumettez-nous votre texte en suivant ces directives.