The farming business has gone through some rapid structural changes in the last few decades. Commercial farm businesses have been growing in size, so the industry is becoming more concentrated in fewer hands.

Most of the food and fibre in the developed world is being produced by a small percentage of the largest farm businesses. In 2007, large-scale family and nonfamily farms made up only 12 percent of US farms but accounted for 84 percent of the value of US production. The largest 20 percent of Canadian farms increased their share of total production from 66 percent in 1971 to 77 percent in 2001.

Scientific investigation has helped farm businesses to grow, bringing better seeds, including those that have been genetically modified; improved pesticides and herbicides, with decreasing environmental impact; better fertilizers and machinery; and in the raising of livestock, higher-quality feeds, with healthier animals and higher yield. These types of advances need to continue if the world is going to be able to feed more than 9 billion people by 2050.

Farming has always been both a business and, for many, a way of life. But the business portion of this combination is taking over rapidly. Farm businesses throughout the developed world and in much of the developing world are becoming much larger as they seek to reduce costs per unit of production. On the Canadian prairies, for example, it is not unusual for grain and oilseed farms to cover over 5,000 hectares; by comparison, the average Saskatchewan farm is about 650 hectares.

Policy-makers must take into account the different set of economic realities faced by small producers – who make up most of the farm businesses in Canada – versus those faced by the massive ones.

On many family farms, the great majority of the revenue comes from off-farm income, such as a salary from a job in town. Net farm income is only one-eighth of the income of farm households across most sizes of farms in the US. In Saskatchewan, according to provincial statistics, off-farm income represented 71 percent of total farm family income in 2009 (the most recent figures available). The need to earn off-farm income when farming fewer hectares takes farmers away from their land and reduces their involvement in labour-intensive farmwork; ultimately, farmers may have to choose between farmwork and other employment, and the farm business may be further reduced, rented out or sold.

Government agricultural policies can also influence farm size. Larger farms receive higher direct government payments than smaller ones and see their risks reduced; they can then operate with more financial leverage and acquire the assets of smaller farms.

Tax policy and measures to control inflation have an impact too. When inflation is low, growth in the value of farmland tends to equal or exceed inflation rates, especially in the recent past. The tax rate on capital gains from selling farmland is lower than the rate on normal income, and the tax bill can be deferred almost indefinitely as long as the land stays in the immediate family. The combination of these two features makes the ownership of farmland attractive, but the owners don’t always work the land. Many owners rent much of their land to large farm businesses.

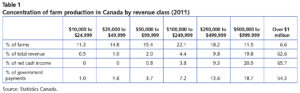

Large farms get most of the available government support simply because they are larger and produce more output. The largest 18.1 percent of Canada’s farms (with $500,000 or more in annual revenue) received 73 percent of the government payments in 2011 (table 1). But small farms depend more on this support because it makes up a bigger share of their revenues.

Concentration of agricultural production will continue, with fewer and larger farm businesses. Farming is headed for more industrialization and greater coordination of production and distribution systems, although some small and medium-sized farms find ways to remain profitable. Niche market farm businesses, part-time farms for those with off-farm income and lifestyle farms will play a part in the sector but will contribute only a small portion of food production.

Concentration of agricultural production will continue, with fewer and larger farm businesses. Farming is headed for more industrialization and greater coordination of production and distribution systems, although some small and medium-sized farms find ways to remain profitable. Niche market farm businesses, part-time farms for those with off-farm income and lifestyle farms will play a part in the sector but will contribute only a small portion of food production.

Canada gains from this structural change by maintaining or improving global competitiveness, increasing productivity, lowering consumer prices and responding to consumer demands for quality, variety and accountability in food supplies. But there are losses too: the replacement of cash markets by contracts with prices negotiated in advance, and the disappearance of cooperative mechanisms such as the Saskatchewan Wheat Pool, which exercised bargaining power on behalf of all of its thousands of member producers.

As the federal, provincial and territorial governments complete work on a new agricultural policy framework and look to the creation of a national food policy, they must consider the differing needs of large farms and small farms. Large farms produce most of the output and are run as businesses; they need policies that recognize their contribution to the economy. Small farms form the majority of farm businesses but are not very important as producers — however, they contribute immensely to the social fabric of rural areas. Each group needs its own set of agricultural policies.

This article is part of the Canadian Agriculture at the Cutting Edge special feature.

Photo: Prime Minister Justin Trudeau chats with Rod Lewis, left, and Lewis’s son at their Lewis Land Limited farm near Gray, Sask., Thursday, April 27, 2017. THE CANADIAN PRESS/Mark Taylor.

Do you have something to say about the article you just read? Be part of the Policy Options discussion, and send in your own submission. Here is a link on how to do it. | Souhaitez-vous réagir à cet article ? Joignez-vous aux débats d’Options politiques et soumettez-nous votre texte en suivant ces directives.