What is populism? How does it manifest itself? What are its causes? And is Canada susceptible to the allure of populist politics? These questions are increasingly top of mind for policy-makers and elected officials across the intellectual and political spectrum.

A growing body of scholarship casts new light on the potential nexus between wealth distribution, intergenerational mobility and the makings of political populism. These articles, commentaries and polls ought to be essential reading for parliamentarians this summer.

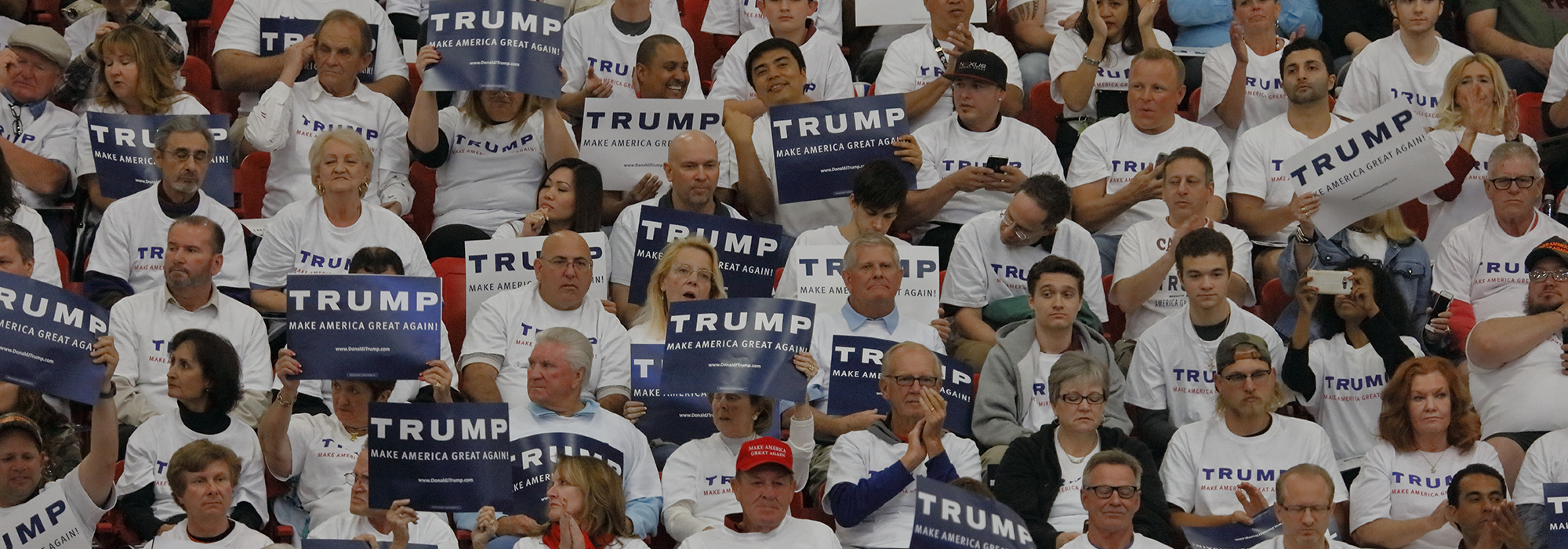

Cas Mudde is a University of Georgia political scientist whose research and writing on populism has thrust him into the public spotlight in recent years. He presents a nuanced understanding of populism as a “thin-centered ideology” that sees society as divided between elites and regular people. Populism is thus more a stance or a rhetoric, rather than a well-developed world view or a set of policy prescriptions.

It’s also not, according to Mudde, inherently bad. Of course, it can manifest itself in divisive and illiberal ways in certain cases and has done so. But, in a 2015 column in the Guardian, he argues that a positive feature of populism is that it can force elites to address issues that they would prefer to regard as settled questions. As Mudde puts it: “[Populism] criticizes the exclusion of important issues from the political agenda by elites and calls for their repoliticization.” What these issues are and what solutions are put forward ultimately depend on national or local circumstances and what “thicker” ideologies, such as economic collectivism or right-wing nationalism, the populist movement comes to associate itself with.

A New York Times article recently offered an explanation for how Canada has “resisted” the populist wave. Its main thesis is that we have not witnessed political populism because of “strategic decisions, powerful institutional incentives, strong minority coalitions and idiosyncratic circumstances.”

There’s no doubt considerable truth to the author’s findings; for instance, Canada does have a greater economic orientation in its immigration policies. But the case is, in our view, overstated. Bromides about multiculturalism (“a mosaic rather than a melting pot”) are an inadequate explanation. A single visit to Toronto cannot reveal broader economic, political and social attitudes across the country. It seems presumptuous to assume on this basis that Canada is somehow immune to the populist trends seen elsewhere. Canadian policy-makers cannot afford to grow complacent about Canada’s economic, political and social inclusivity.

A June 2017 survey by the Canadian Press/EKOS Politics looked at Canadian attitudes and insights on populism. The results show that “northern populism” may be on the rise in Canada: more than 70 percent of Canadians believe that the conditions for political populism are present. One in five respondents say that a populist movement would be a positive development.

There are limitations to the conclusions that can be drawn from such polling data. The survey seems to assume that “populism” is the same at any time, anywhere, and it neglects the extent to which the circumstances are different in various countries. There’s a tendency to overstate commonalities when one searches for a general theory or a simple narrative.

Populism tends to take on national or local characteristics. Its manifestation in Canada would probably assume Canadian features such as an urban/rural divide (as we recently described) or regionalism, as it did in the late 1980s with the Reform Party. Former Toronto Mayor Rob Ford’s political resonance is another good example of how populism is shaped by local circumstances. Ford appealed to underrepresented constituents in Toronto’s often forgotten inner suburbs to rally voters against the city’s downtown elites. In adapting to a city with as many