It’s been a little under two weeks since the UK election, when support for Theresa May’s government plunged. She was left with not a super-majority as she hoped, but a minority situation. Much of the UK’s political future is murky.

Here, I outline 10 major unknowns for Brits.

- What flavour of government will they get?

Theresa May said she had secured the support of the Northern Irish Democratic Unionist Party (DUP), but it is clear that a deal has not yet been reached. May was forced to postpone the Queen’s Speech, and it’s possible she still will not have a deal by that point.

Speculation is increasing that May might try to govern as a minority, but May’s own colleagues, who are likely to challenge her leadership in a minority situation, are a complicating factor.

Further, it is in the interests of the other parties to force another election, rather than allow May to govern as a minority. Polls show Labour would do significantly better today if an election were held, in part due to Corbyn’s grassroots popularity on the campaign trail, and in part due to a series of missteps by May.

All that to say, it’s still unclear what flavour of government Britain will get. A short-term May government with DUP support is likely, but so is another election.

- What’s this thing about Northern Ireland?

A potential deal with the DUP is controversial because of the risk of destabilizing Northern Irish peace. Under the Good Friday Agreement, the British government acts as a neutral convener to maintain the power-sharing agreement that brought peace after centuries of strife. There are fears that a Conservative deal with the DUP will change that neutrality. Since we don’t yet know what May has traded or is willing to trade for DUP support, we can’t say whether Britain’s essential, neutral role has been comprised.

- Another election? Seriously?

Yep. Since the Fixed Term Parliament Act (FTPA), it’s much harder for the House of Commons to trigger an election by defeating a government. In the past, a budget was considered a confidence vote, and by convention, the government would resign if it couldn’t pass a budget. This is no longer the case. A government must either lose an explicit no confidence motion, or two-thirds of the chamber must vote for an early election.

So, there are only two ways for the opposition to defeat a May government. If they pick the first option, they then have 14 days to attempt to form a viable government. Given the rainbow coalition of parties and interests, it’s extremely unlikely the opposition as it stands could cobble together a government.

It may come down to timing – when is it best to trigger an election? There is no doubt May’s colleagues are keenly surveying the landscape and deciding on their own best timing to challenge her. How does this factor into an election? Is it best to trigger an election before the Conservatives oust May, or wait to see what happens to May?

It’s rather like playing chess – so many variables, so much uncertainty.

- But wait, Corbyn could be PM?

He could! It’s unlikely the opposition as it stands could cobble together a viable government, especially with such varying positions on Brexit. But if another election were called over summer, the numbers currently show Labour coming out on top.

- Grenfell Tower changed everything

The UK faced three unprecedented events during or right after the election: the Manchester and London Bridge attacks, and the horrendous fire at Grenfell Tower. It’s hard to analyze how terrorist attacks affected the vote, but it is clear Grenfell Tower is tapping into a broader sentiment that hurts May and benefits Labour. The fire is being seen as an almost inevitable consequence of Conservative austerity policies, Conservative changes to social housing, and governments that prioritize the wealthy at the expense of the poor and racialized minorities, like the inhabitants on Grenfell Tower. There is the sense of a sea-change, a pivotal moment for British society, and if it turns, it will turn on May and the Conservatives.

- May’s public persona

During the election, May to a large extent focused the Conservative campaign on herself. Her name was in large lettering, her party’s name relegated to a footnote. It seemed the strategy was to present her as a sturdy pair of hands to steer the country through Brexit. She was boring and technocratic, but deliberately so. To that end, her campaign events were tightly controlled, and she didn’t attend election debates. In the last two weeks, as Corbyn found his niche in grassroots, preacher-style rallies, May looked robotic, distant and frightened of the public.

In the context of this perception, May’s response to the Grenfell Tower fire only entrenched the narrative. She didn’t meet families and survivors until day four after the fire. And then she only did so in private. Contrast this with Corbyn’s immediate and unscripted visit, where he stood in the street and listened, and even the Queen’s visit, where she met with families too.

May’s own colleagues are publicly expressing their unhappiness with her public image. Media coverage of her “leadership failure” has been savage. She has been portrayed as out of touch, and completely unable to understand the mood of the country. At a time of near-crisis, when leaders should listen, show calm and determination and, most importantly, instinctively understand the anger, the fear and the historical reasons for such a tragedy, May appears completely lost.

- Conservative Party machinations

Conservative Party divisions over Europe have ended the service of every Tory PM since Churchill. And they are likely to claim Theresa May’s career too. As someone said, the cabinet is currently held together by members’ utter distrust of each other. They are like a band of thieves, bruised and cut from years of brutal internal battles and attempts to depose their leaders. There is no doubt May’s colleagues – Boris Johnson, Michael Gove, and David Davis especially – are using this time to plot their next leadership moves. George Osborne gleefully described May as « a dead woman walking,” but how and when she gets deposed, and by whom, will be a complicated game.

- How will Brexit happen?

Ah yes, the small matter of Brexit. Not only has Number 10 lost six key staff members in the past two months, May is contending with trying to form government, dealing with Grenfell Towers and starting Brexit negotiations.

The EU negotiators have already taken advantage of May’s weakened position, forcing a series of concessions over when and how negotiations will take place. Media reports describe the British negotiating team as woefully unprepared, with no real demands or capacity to engage.

In addition, based on the collapse of the UKIP vote – down 3 million from 2015 to 2017 – one could reasonably infer the British people are less comfortable with the May government’s hard Brexit stance. During the Brexit referendum campaign, even pro-leave leaders were discussing versions of a “soft” Brexit, maintaining key links to Europe and its single market. Suddenly, under May, the stance shifted to a hard Brexit, with “no deal is better than a bad deal” as the mantra.

EU negotiators and leaders have, with reason, concluded that May has no backing to negotiate a hard Brexit. At one point, they were insisting she first pass a Queen’s Speech before negotiations began, to prove she had a mandate.

Meanwhile, opposition MPs also say May has no mandate to negotiate for Britain, and have called for an all-party, national interest negotiating team.

- No really, Brexit?

There is indeed an outside chance it will never happen. It was never going to happen in the form most Brexiteers wanted – that vision was always impossible. But EU leaders have been opening the door for Britain to revoke its invocation of article 50. EU leaders see a faint possibility, in the wavering, hesitant and weak position in which Britain finds itself, to tempt Britain back into the European Union. If it did re-enter, it would not be the same as it was before, that much has been made clear. But there is a path (albeit a tangled and treacherous one) for a new Conservative (or Labour) PM, to quietly ensure Brexit, as it is currently conceived, doesn’t work out, and negotiate a new relationship with the EU.

- What does 2020 look like?

Goodness knows what the future holds, but I’d put money on no Brexit, as it is currently conceived. Perhaps Britain will be half in the EU, like Switzerland or Norway? At this moment, I’d fancy my chances with predicting a Labour government too.

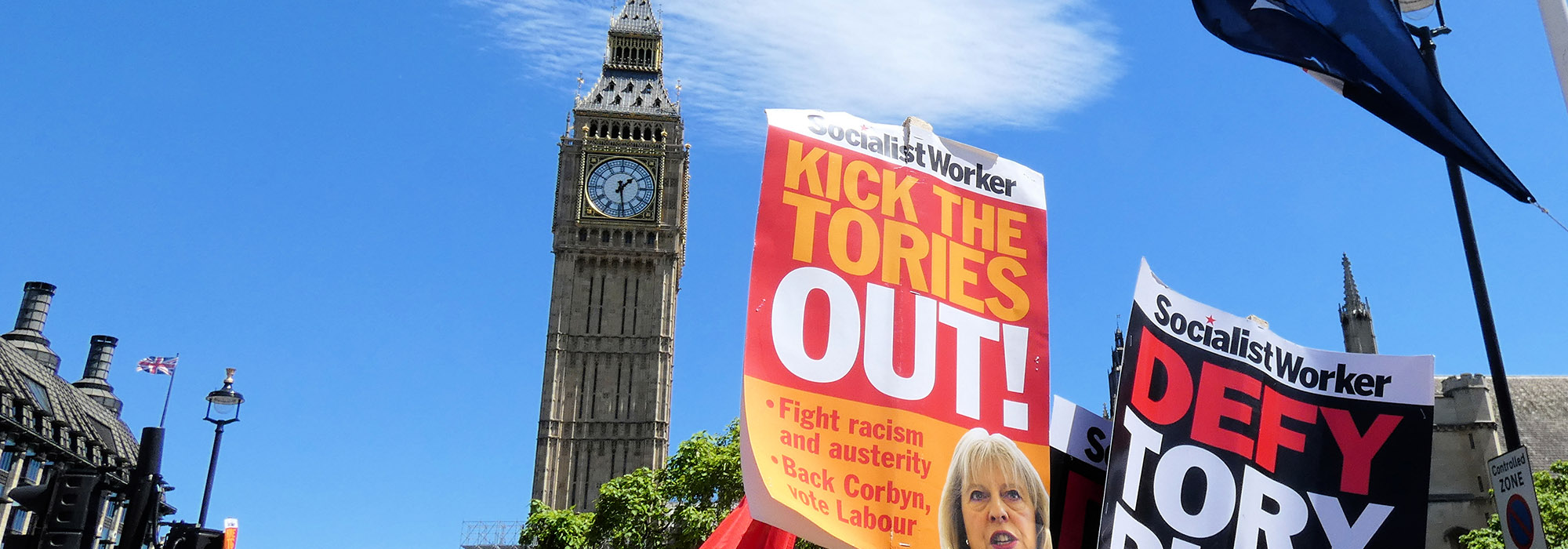

Photo: Anti-Theresa May protest takes place in Parliament Square following the General Election. Shutterstock/Brian Minkoff

Do you have something to say about the article you just read? Be part of the Policy Options discussion, and send in your own submission. Here is a link on how to do it. | Souhaitez-vous réagir à cet article ? Joignez-vous aux débats d’Options politiques et soumettez-nous votre texte en suivant ces directives.