It has been six weeks since British Columbians went to the polls. The absentee ballots have been counted, the recounts are over, and the newly elected members have been sworn in. Remarkably, it still feels more like intermission than curtains down. The BC Liberals — still technically the government — lost their majority but maintained a plurality of seats, and Premier Christy Clark has signalled her desire to reign at the head of a minority government. However, as Clark herself admitted, the Liberals do not have enough seats to govern, since the New Democratic Party (NDP) and Greens, who hold a razor-thin majority in combination, have offered to work together to run the province.

The parties have been jockeying over who will serve as the Speaker of the legislature. At first, no party wanted the role. To take the necessarily nonpartisan job as the legislature’s referee means giving up a voting member of the Legislative Assembly (MLA) and slipping one vote further away from a claim on government. The beleaguered Liberals initially said that none of their members would run for the Speaker’s post, leading a party insider to suggest that any Liberal who puts his or her name forward would be an instant pariah. In mid-June the party changed its tune and said someone would stand; in Clark’s words, whichever party forms the government “has a responsibility to ensure a Speaker.” However, this means a Liberal Speaker will likely serve only until after the Speech from the Throne is read on June 22, and the Liberals are defeated by the NDP-Green alliance in a motion of nonconfidence. Then it will be the “responsibility” of the new government to offer a Speaker.

But the NDP and the Greens simply don’t have a member to spare, since offering a Speaker would mean giving up their combined one-MLA lead over the Liberals and thus their claim to government. Would Lieutenant-Governor Judith Guichon offer the NDP the opportunity to form government when they have only the same number of seats as the defeated Liberals, and must rely on an agreement — not a coalition — with the Greens? The answer is far from clear.

The province’s current quagmire has led some to call for an immediate return to the polls. It’s not just pundits floating the idea. In a letter to supporters, the NDP has asked for donations in case it “face[s] an election call in just a couple of weeks.” Clark and the BC Liberals say they are prepared to serve and fall in opposition, and the sometimes quirky finance minister, Mike De Jong, even entertained journalists at the cabinet swearing-in by singing, “Here for a good time, not a long time.”

But another election is not the ideal solution to the current political mess. Democracy involves more than asking voters to go to the polls until the results shake out a large majority. Voters made their choice on May 9, and their representatives have a responsibility to make the legislature work with the hand British Columbians dealt them. Although elections are a necessary and important part of democracy, they are expensive for taxpayers (the last election cost $44 million) and can be gruelling for candidates.

Economic and social inequalities make the costs of campaigns and elections especially burdensome for women and members of other historically disadvantaged groups, contributing to their underrepresentation in legislatures. The gender wage gap — women in BC earn just 78 cents for every dollar men earn — means that the financial cost of running in an election is disproportionately hard on women. Because women are underrepresented in the old boys’ club of politics, business and finance, they are also less likely to have the financial networks and political capital — and access to wealthy donors and political information — available to many men.

Economic and social inequalities make the costs of campaigns and elections especially burdensome for women and members of other historically disadvantaged groups, contributing to their underrepresentation in legislatures.

Elections are also extremely demanding on candidates’ time, and on their campaign staff and volunteers. Again, this burden may be especially likely to dissuade women, particularly those with young children, from pursuing politics, since women bear disproportionately more family care responsibilities. According to Statistics Canada, women spend twice as much time as men caring for children, even when women work outside the home. In the absence of meaningful accommodation and support, this inequality filters into the political sphere and is a major contributor to women’s underrepresentation. Forthcoming research shows that women who are elected representatives are far less likely than male representatives to have children: while nearly all male MPs (90 percent) have children, less than three-quarters (70 percent) of women in the House of Commons have children. Women in politics who do have children tend to have fewer, and they tend to wait until their children are older before entering the political arena.

Women in politics are also more likely to face harassment, which can be especially acute during elections. Harassment often takes the form of degrading comments — including sexual innuendo and threats of physical and sexual violence — and it takes a psychological toll. Over the past year, women in politics across the country shared and exposed the harassment and violence they face, and many raised concerns that harassment was dissuading other women from entering politics.

These financial and personal costs mean that a second election would be especially punishing for women. Furthermore, if the last election offers any indication, women who run also reap fewer rewards. BC’s 2017 election results reveal that although 54 percent of men running for the major two parties won their seats, only 40 percent of women candidates won theirs. Why? The answer is that women were more likely to run in “lost cause” ridings, where their party lost by 10 percentage points or more in the previous election (in 2013). Furthermore, women were less likely to run in “winning ridings,” where their party won by 10 percentage points or more in the previous election. Even incumbent women face tougher races than do their male colleagues.

If democracy is also about equality of participation, these realities should not be ignored by those looking for solutions to BC’s current political quagmire. Instead of holding another election, it’s time to let the women and men who were elected sit in the legislature and do the job of governing the province and representing their constituents. The next government — however long it lasts and of whatever stripe — should work to address equality issues and make provincial politics more open to women and other historically marginalized groups.

For instance, lower campaign spending limits would help close the gap between those social group members who traditionally have access to the old boys’ club of campaign donors and those who do not. Regulating nomination races under the BC Election Act to ensure some level of transparency, fairness and predictability could go far in increasing the number of women candidates, particularly in winnable ridings. And emulating Manitoba’s policy of reimbursing candidates for 100 percent of the costs of care expenses during campaigns would help make running for office more woman-friendly. A clear, proactive policy on harassment is also needed to help prevent and address the abuse many women politicians face.

Women are contributing to British Columbia in business, in the public sector and through work in their communities. The changes proposed here would bring more women and their experience and expertise into politics. If the last month and the events that can be expected in the coming weeks are any indication, we could use all the help we can get.

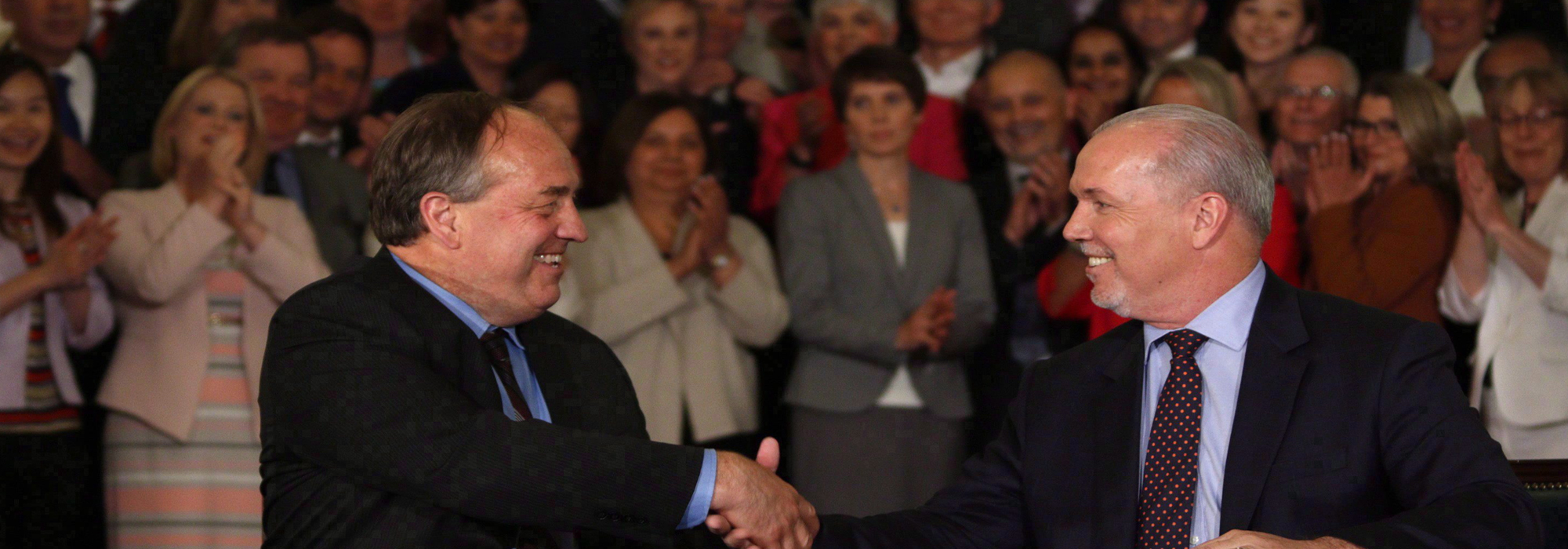

Photo: BC NDP leader John Horgan and BC Green party leader Andrew Weaver shake hands after signing an agreement on creating a stable minority government during a press conference in the Hall of Honour at Legislature in Victoria on May 30, 2017. The Green party has agreed to support a New Democrat minority government by voting with them on confidence matters. THE CANADIAN PRESS/Chad Hipolito

Do you have something to say about the article you just read? Be part of the Policy Options discussion, and send in your own submission. Here is a link on how to do it. | Souhaitez-vous réagir à cet article ? Joignez-vous aux débats d’Options politiques et soumettez-nous votre texte en suivant ces directives.