Recent foreign and defence policy announcements by the Trudeau government have been just about as consequential as they come. On June 13, Global Affairs Minister Chrystia Freeland laid out the broad principles that will guide Canadian foreign policy going forward. She invoked Canada’s efforts in the Second World War and its contributions to postwar peace and stability in her speech. And she signalled that the long, steady slide in that role, overseen by Liberal and Conservative governments alike, is over.

Canada, she intoned, is back.

This was followed by Defence Minister Harjit Sajjan’s announcement of a substantial boost to the Canadian Armed Forces. Both speeches reflect the challenges that the erratic and unconventional policies of the Trump administration represent.

They were motivated by the unhappy realization that President Trump may represent an existential threat to the international arrangements under which Canada has conducted its foreign and defence policies for the past 70 years. These arrangements reflect the realities of the postwar period, when the United States was the guarantor of global peace and international financial stability. The US assumed this role by default, not necessarily by choice. Trump seems prepared to cede these responsibilities. Regardless, although the US was instrumental in creating an “architecture” of treaties and treaty-based international organizations to support it in this role, as Minister Freeland observed, Canada played an outsized role in this architecture by virtue of its enormous contributions to the war effort. It was a time in which Canada “punched above its weight” in the international ring.

The willingness of the Trudeau government to commit Canada to once again punch above its weight class is both admirable and necessary. It is admirable because providing leadership in global affairs will entail commitment; it would be much easier to ignore the shifts in international arrangements and focus solely on domestic policy and US relations or, as a friend derisively says, a policy of “making Canada the best darn Michigan possible.” It is necessary because a country that is not prepared to police the territorial integrity of its borders cannot be considered sovereign. Moreover, Canada’s economy depends on access to global markets and is affected by shifts in global commodity prices. Our economic self-interest dictates that we help shape the future of international trade, financial and monetary arrangements.

This is no small feat. It will require careful management of Canada’s economic and strategic interests. There are three rounds, so to speak, in this fight.

Round 1: Managing the US

The US has been, is and will remain our most important trade and security partner. Successive generations of Canadians have grown up secure in the knowledge that the US — while at times difficult to comprehend — was a steady and reliable neighbour. Trump has cast doubt on that certainty. His offhand remarks about the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), which has been the foundation of international security cooperation for seven decades, his derogatory, oafish behaviour toward leaders representing democratic governments and his inexplicable regard for political strongmen in weak democracies all point to an individual ignorant of history and incurious to learn.

Nevertheless, the Trudeau government must deal with him. For the past several months, I suspect, the government has hoped to “manage” the mercurial man in the White House. That strategy made sense. But it rested on the underlying assumption that much of Trump’s bluster was feigned: a ruse intended to appeal to his political base. The government has probably come to the realization, however, that that assumption may not be correct. If media reports are to believed, the President really did come very close to scrapping NAFTA, which was saved only by the last-minute intervention of the US Secretary of Agriculture, who pointed out that American farmers who voted for Candidate Trump would be harmed. This points to a strategy to safeguard Canadian interests in which we focus on members of Congress from states that benefit the most from NAFTA and work directly with states and cities that are committed to the climate change fight.

The loss of NAFTA would have entailed significant disruption to the Canadian economy. Similarly, Canada benefits enormously from the protection of the joint North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD) umbrella. A sensible strategy, therefore, is to avoid potential frictions that might be used as a chip in Trump’s “art of the deal” bargaining. So if Trump wants NATO members to meet their commitments to spend 2 percent of GDP on defence, that is the price that Canada must pay to remain a partner in NORAD. If Canada is not a partner, it would be a supplicant and not truly sovereign.

Round 2: Strengthening NAFTA

As the episode with the Agriculture Secretary revealed, credible threats are what a deal maker respects. Unfortunately, Canada lacks the capacity to retaliate in a meaningful way; while US economic interests could be targeted, any measures that get Washington’s attention would also harm Canadian interests. Mexico, on the other hand, has economic (agricultural) and political (immigration) leverage that it could exercise. Moreover, Canadian firms have large investments in Mexico that form part of their global supply chains. The loss of these chains would make Canadian firms less competitive in global markets. When Canada works with Mexico to bring NAFTA into the 21st century — for example, by including digital technologies and other services that did not exist a quarter century ago— the effort advances their shared economic interests, which go far beyond trade.

By promoting Mexican economic growth, free trade would also foster development and political stability, providing obvious benefits for Mexico and creating an even stronger partner for Canada. The US, meanwhile, benefits because higher wages in Mexico mean less illegal immigration into the US. If someone has pointed that out to the President, it clearly has not registered.

Round 3: Strengthening the multilateral system

The final round is all about working with partners to strengthen the multilateral system and the international institutions — such as the World Trade Organization, the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the World Bank and regional development banks — that promote shared prosperity through global trade and international financial and economic stability.

These institutions changed the way in which nations view the global economy. This postwar international architecture succeeded in transforming the global economy from the beggar-thy-neighbour zero-sum game of the 1930s, in which one wins at another’s expense, into a positive-sum game that allows all “players” to benefit, provided they adhere to the rules of the game. That success is now at risk.

Whether through conscious policy or unintended effect, Trump poses a threat to this system. In a sense, the IMF and its sister institutions grow the “pie” to be divided by all, but they do so by limiting the scope for discretionary actions by all the players, including the biggest. Trump believes that the rules are rigged against the US — a curious proposition, given that it has had the biggest voice in their development. He therefore seems to want to peel away individual countries from multilateral commitments and negotiate with them on a bilateral basis. As the biggest player, capable of wielding the biggest threats, that would be good for the US. It wouldn’t necessarily be good for others, however.

These institutions amplify Canada’s voice and extend its influence in global decision-making, helping to protect sovereign interests. The Trudeau government is right to assert its intent to play a more aggressive role in them, as was the case decades ago. But filling the vacuum left by the possible retreat of the US will require that Canada provide the leadership needed to mobilize others. This means avoiding the temptation to shoehorn discussions of domestic policies into multilateral agendas, at the IMF and other institutions. And it will require ideas.

The Global Affairs Minister’s speech was long on ideals, short on ideas. That may have been entirely intentional; it may have been an expression of the principles on which the government will base its policies going forward. But the government will have to lay out concrete measures to strengthen the institutions of international cooperation and sustain multilateralism if Canada is to truly punch above its weight.

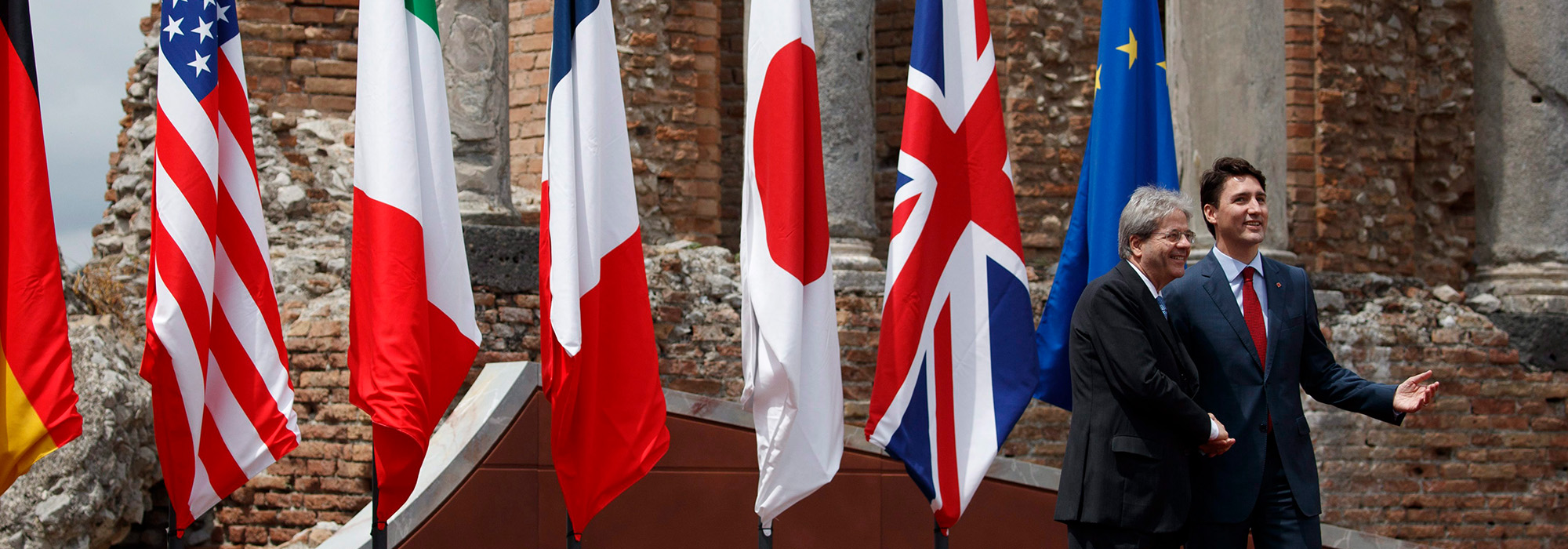

Photo: Italian Prime Minister Paolo Gentiloni greets Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau before a G7 leaders family photo. (AP Photo/Evan Vucci)

Do you have something to say about the article you just read? Be part of the Policy Options discussion, and send in your own submission. Here is a link on how to do it. | Souhaitez-vous réagir à cet article ? Joignez-vous aux débats d’Options politiques et soumettez-nous votre texte en suivant ces directives.