There were few moments in President John F. Kennedy’s brief tenure in office that seemed as promising as the afternoon of May 20, 1962, in New York City. In front of 20,000 senior citizens gathered at Madison Square Garden, Kennedy delivered a ringing defence of the health insurance legislation for the aged making its way through the Congress, and a none-too-subtle attack on its opponents in the medical and insurance professions. “This,” exhorted Kennedy, “is a problem whose solution is long overdue.” The crowd was enthusiastically appreciative, but even Kennedy’s supporters were skeptical about whether the speech had done enough to convince the much larger audience of television viewers — and voters — to whom the event was carried live by the three major networks of the time. In fact, it would take three more years, and a significant shift in the composition of the Congress, for Medicare to finally see the light of day in the United States.

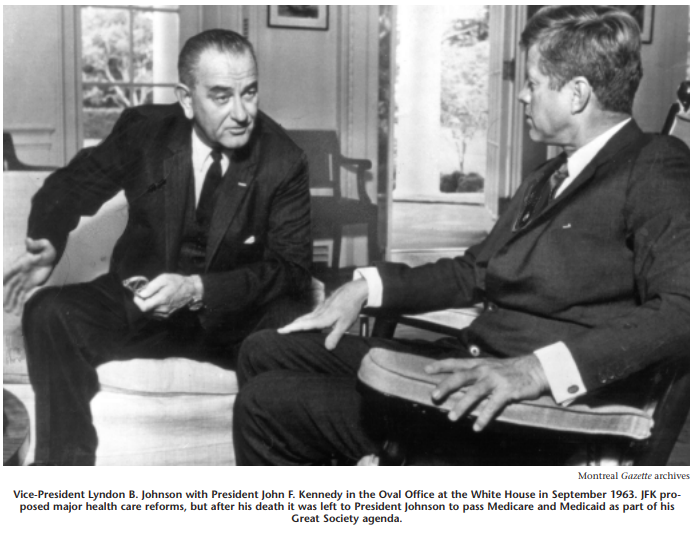

The Kennedy administration would be remembered for many things — the defusing of the Cuban missile crisis, American involvement in Vietnam, and the controversy over civil rights — but health insurance would turn out to be one of its important legacies. The legislation President Kennedy defended in that 1962 speech was to lay the foundation for the Medicare and Medicaid bills signed into law by his successor Lyndon Johnson, and would spur his surviving brother, Senator Edward Kennedy, to be a life-long advocate for universal health insurance in the US.

President Barack Obama’s more recent engagement on this issue should be seen as part of a continuum of presidential efforts designed to shore up support for the difficult goal of health care reform. And it should also be understood as part of a very difficult historical trajectory. From the feisty offence plays of Harry Truman through to Bill Clinton’s all-out efforts, the domestic agenda of US politics has been marked by the battle scars of that great, unfinished business: universal health insurance for all Americans.

The remarkable exceptionalism of the United States in health policy is even more intriguing given the considerable interest in health insurance that stretches back to the early decades of the twentieth century during the progressive era. Indeed, by the mid-1910s, European precedents had convinced many social reformers and medical professionals that it was “inevitable” in the United States. The first attempts to promote government involvement were led by the irrepressible Theodore Roosevelt, who formally endorsed compulsory health insurance as leader of the Bull Moose Progressives in 1912. More plausible were the state-level initiatives (particularly strong in California) but, as they were based on the German social insurance model, they were denounced as “foreign” infiltration and did not survive the First World War.

President Barack Obama’s more recent engagement on this issue should be seen as part of a continuum of presidential efforts designed to shore up support for the difficult goal of health care reform.

The election of Franklin Roosevelt, and his determination to actively respond to the Great Depression, would lay the basis for the Social Security Act of 1935 and affirm federal leadership in American social policy. Roosevelt’s hand-picked group of advisers showed interest in designing a health insurance provision, but the president was keenly aware of its vulnerability alongside the proposals for old age pensions, social assistance, and unemployment insurance. Health insurance was eventually left out of the 1935 bill, due to the controversy associated with the issue, fostered in large part by the opposition of business and the medical profession allied with conservative interests in Congress. Nonetheless, the Social Security Act was ground-breaking legislation: nothing in Canada at the time could compare (indeed, Mackenzie King was privately appalled at FDR’s desertion of classic liberalism, while R. B. Bennett’s “New Deal” was but a shadow of the original). The provisions of the Social Security Act would have a resounding impact on the future path of health care reform in the United States.

Roosevelt returned, belatedly, to health insurance once the Great Depression was over. As the Second World War wore on, Roosevelt became intrigued by British discussions of postwar reconstruction and the notion of “cradle-to-grave” security (which intimates credit to him, not to Lord Beveridge). Cautious about translating this vision into legislation, it was not until the 1944 presidential campaign in the final months of war that Roosevelt focused on an “economic bill of rights,” including the right to medical care.

When Harry Truman was left to take on Roosevelt’s legacy, he was determined to maintain existing social programs to highlight the continuity in leadership, and to champion health insurance as a way of carving out his own reform legacy. Unlike his predecessor, Truman was prepared to forge ahead despite the controversy surrounding health insurance. The former straight-ticket New Deal senator must have been aware of the opposition to such an initiative. Perhaps, like Kennedy, Clinton and Obama after him, he misjudged their strength; more likely, as his contemporaries noted, “he didn’t give a damn.”

On November 19, 1945, Truman presented an historic message to Congress on health reform, the first president ever to do so, emphasizing the link to Roosevelt’s call for “freedom from want.” His proposals (including investment in hospital construction, public health, medical training and research, and a plan for “prepayment of medical costs”) were endorsed by many groups, including organized labour, and for a time they enjoyed substantial public support. But it is difficult to overestimate the hostility to health insurance in the 1940s, not only among Republicans, but more acutely within Democratic ranks. The “conservative coalition”’ that had emerged in opposition to the New Deal grew ever more powerful as southern Democrats flexed their political muscle against Truman — the Dixiecrats of the 1940s make today’s Blue Dog Democrats look like amiable puppies. Added to this was the onslaught of public relations campaigns led by the American Medical Association. The lurid spectre of “socialized medicine” turned out to be particularly successful in the context of the nascent Cold War.

Truman tried no less than three times to press forward health insurance legislation but, like Bill Clinton’s, his failure would be a crucial factor in the Republican’s regaining of Congress and, eventually, the presidency. During the 1950s, the frustration engendered by anti-health insurance campaigns and the sustained hostility in the Congress forced reformers to refocus their attempts on something more modest — and more politically feasible. Two trends cemented this approach. The Social Security Act had created a new “entitlement” group: the elderly in America. Politically appealing in a motherhood-and-apple-pie sort of way, the elderly were also becoming a powerful lobby in their own right, and the importance of the “rocking chair” vote was apparent. In addition, in the absence of government health insurance initiatives, employer-based benefits and private insurance were filling the vacuum, leaving the elderly as the most vulnerable to the effects of ill health and medical costs.

From this strategy emerged the proposals that would lead to Kennedy’s initiatives, labelled “the foot in the door to socialized medicine” by its opponents. It would take no less than the breakthrough 1964 election, President Johnson’s epic War on Poverty, and the concerted bipartisan politicking for which Congress is so famous, for publicly financed health insurance under Medicare and Medicaid to be passed in the United States. The final compromise included a social insurance program for hospital insurance for the elderly (Medicare Part A), a voluntary medical insurance plan (Medicare Part B), and a means-tested addition to cover the medically indigent (Medicaid).

It was not without reluctance that US reformers turned away from “universal” health insurance for the time being, and this would become the most important feature distinguishing it from the Canadian approach. The Social Security Act had set the precedent for age-based cleavages in the social benefits, and it reinforced the idea of “deserving” groups. In Canada, no such precedent had been firmly institutionalized, and while reform efforts would begin with hospital insurance first, and then medical care later, the universality principle held firm.

Through Medicare and Medicaid, the US government took on the responsibility to guarantee access to health care for those groups most likely to be shut out of the voluntary and employer-based market for health insurance in the United States. In other words, government was relegated to the role of insuring groups with the highest actuarial risk. Although both insurance interests and the medical lobby were initially hostile to such reforms, they were given important roles in the organization and delivery of these benefits. As originally written, Medicare instructed the federal government to cover any “reasonable costs” billed by hospitals and doctors. The public sector, therefore, was obliged to participate in the private market for health care, even though it had little influence in controlling costs.

The steep increase in the cost of and the explosion in public expenditures for health care in the United States led to a shift in the focus of health care reform from improving access to health insurance to controlling the costs of health care. The Nixon administration’s program for group-based health insurance was unsuccessful, although it did encourage the proliferation of health maintenance organizations (HMOs) in the United States and was considered the forerunner of “managed care” proposals. Throughout the 1970s, congressional Democrats (led by Senator Edward Kennedy) attempted to link access and cost concerns with renewed demands for national health insurance, but the enduring divisions within the Democratic Party on the issue, the hostility of the Republican opposition and the persistent resistance of provider groups precluded such reform initiatives.

The widespread reluctance to embark on new spending for entitlement programs and the conservative backlash pushed national health insurance out of the spotlight in the 1980s. At this point, reforming health care meant reducing federal expenditures, particularly spending on entitlement programs such as Medicare and Medicaid. Federal payments for Medicaid programs were substantially reduced, forcing states to modify their benefits and eligibility criteria. Medicare was a more difficult target, since it enjoyed widespread bipartisan support, bolstered by a large and politically influential clientele, the aged. Despite the free market rhetoric of the administration, the focus of health care reform shifted to the regulation of the market for health services by imposing limits on Medicare payments to doctors and hospitals. In 1982, the reimbursement of “reasonable costs” was replaced with a prospective schedule of fees based on “diagnostic related groups” (or DRGs), and Medicare beneficiaries were encouraged to use “preferred provider organizations” (or PPOs). In 1984 and 1986, freezes were imposed on Medicare reimbursements for physician fees. Private insurers, at the same time, began to impose greater restrictions on the type and extent of reimbursement they would cover. Ironically, American doctors, who had fought compulsory national health care insurance on the grounds of physician autonomy, now found themselves increasingly regulated by insurers and more awash in paperwork and billing problems than their Canadian counterparts working within a public health insurance system.

By the late 1980s, as health care expenditures continued to soar in the United States, cost concerns became inextricably related to questions of access to care. A major health care initiative in this period, the 1988 Medicare Catastrophic Coverage Act, was designed to improve the access by the elderly to long-term care. The measure was repealed under pressure from the elderly, who objected to the selffinancing of the program through premiums and increased personal income tax. The passage of this bill reflected a bipartisan recognition of the linkage between problems of cost and access, but its subsequent demise revealed the limits of incremental change and pointed toward the need for a more fundamental restructuring of the American health care system.

The retrenchment of federal financing of existing programs and the relative inaction in addressing problems of health care costs and access encouraged states to think about initiating their own health care reform. Until 1988, the only successful statelevel health insurance model was that of Hawaii, which combined mandatory employer-based coverage with cost containment. By 1992, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Vermont and Florida had enacted (though not yet implemented) health care legislation; Oregon also proposed the rationing of certain Medicaid benefits. This state-level activity bolstered confidence in the idea that a national health insurance system could develop from subnational initiatives, as it had in Canada, and that such initiatives could allow states to experiment with different types of reform, from managed care to single-payer plans. But the problems surrounding state action and the difficulty of reaching consensus in state legislatures highlighted the limits of state-led reform in the US, and the dangers of a “crazy quilt” approach to health care (unlike the coordinated Canadian system) in the absence of a clear federal policy direction.

In 1991, Democrat Harris Wofford’s upset victory over former attorney-general Richard Thornburgh in the Pennsylvania Senate race revealed the emerging political stakes of health care reform as a national issue on the domestic agenda. This also showed the depth of dissatisfaction among voters with the perceived inaction of the administration of the first George Bush on the issue. In a recession-wracked economy, working Americans feared for their health care benefits. These fears were intimately tied to concerns about the future viability of the American health care system. The hard-to-define but politically powerful American “middle class” seemed worried that their access to affordable health insurance was in jeopardy, and were apprehensive about the future of the health care system. The medical lobby began to raise concerns about the problems of access to care, in particular the burden of caring for the uninsured and the limits imposed on their practices by thirdparty insurers. Once a bulwark against government intervention, the American Medical Association now endorsed a “public-private partnership” that would guarantee universal access while preserving the freedom of the medical profession in the health care market. Big business, saddled with a major portion of the American health bill, was increasingly frustrated by the seemingly uncontrollable increase in health care costs and became another unlikely proponent of government regulation.

During the 1992 election campaign, health care reform surged to the centre of the domestic political agenda in the United States. President George H.W. Bush seemed incapable of allaying fears about the economic future of the United States, and of devising a reasonable scenario for health care reform. By contrast, the “health care crisis” became one of the oft-repeated buzzwords of the successful Clinton campaign that, along with “the economy, stupid,” captured the attention of a recession-weary public open to the bold rhetoric of change.

This rhetoric was in evidence on September 22, 1993, as President Clinton delivered an emotional plea before Congress about the urgent need for health care reform in the United States. Clinton’s address reflected the powerful momentum of the health care reform issue, which had helped propel the Democratic Party to the White House. But, like Truman’s and Kennedy’s, the forcefulness of his delivery also reflected the offensive strategy he needed to implement in order to raise public engagement and to face the substantial open hostility of powerful lobbies and their congressional allies.

The first attempts to promote government involvement were led by the irrepressible Theodore Roosevelt, who formally endorsed compulsory health insurance as leader of the Bull Moose Progressives in 1912. More plausible were the state-level initiatives (particularly strong in California) but, as they were based on the German social insurance model, they were denounced as “foreign” infiltration and did not survive the First World War.

As the Clinton administration began to tackle health care reform through a Task Force chaired by the First Lady, Hillary Clinton, several alternatives were already being discussed in policy circles. Interest in the Canadian health care system and its ability to balance cost control and access to care led to suggestions for a single-payer government-financed health insurance system supported by influential health care experts, consumer lobby groups, union organizations, and progressive Democrats. At the other extreme were Republican proposals for tax credits, vouchers and medical savings accounts. In between were suggestions for expanding the existing Medicare model to other groups in society as well as a number of variations on mandating employer health insurance.

How did Canada become an unwitting player in the debate over health care reform in the United States? Essentially, Canada was not unfamiliar to Americans, and proponents of national health insurance had taken an interest in the Canadian experience since the 1970s (even Senator Kennedy had been a fan). Canada was attracting renewed attention as the debate for health care reform heated up in the 1990s, and as the search for solutions focused on issues of cost and access. Advocates of the Canadian model pointed out that a single-payer system could reap substantial savings in the overall costs of health care, while at the same time guaranteeing universal access to comprehensive benefits. A widely cited 1991 report by the United States General Accounting Office projected that such an arrangement could save the United States billions of dollars. Other studies went further to suggest cost savings on administrative waste, malpractice, hospital budgets and fee schedules.

Detractors pounced on Canadian health care to demonstrate the impossibility of single-payer system. Their estimates showed that total costs could actually increase and, ominously, that there was an inevitable trade-off between quality and access. Stories abounded associating the “rationing” of health care and “queuing” for treatment, with arbitrary government control of health care resources and the constraints this imposed on freedom of choice. Media coverage in the US increasingly focused on the shortage of high-technology equipment, waiting lists for surgery, and overcrowding in hospitals. In addition, the Canadian medical community was accused of free-loading off the United States for research, innovative procedures and medical technology. While these attacks against the quality of Canadian health care suffered from the vice of extrapolating apocalyptic scenarios from anecdotal evidence, they ended up having considerable resonance in the US (and became familiar in Canada, as conservative voices on this side of the border took up their claims).

Beyond portraying the Canadian model as undesirable, there was considerable effort to discount it as unfeasible due to the “fundamental” differences between Canada and the United States. In an ironic twist, just as the right in Canada became more pro-American than ever before, arguments about the incompatibility of Canadian and American values became part of the conservative firing squad in the US.

Several influential voices continued to endorse the Canadian model, substantial numbers of Democrats in the House of Representatives supported a single-payer health insurance bill, and single-payer initiatives began to be discussed at the state level. Nevertheless, it was apparent that the single-payer health care was not about to be part of the administration’s reform package.

The Health Security Plan, which emerged in 1993, represented a departure from the basic social insurance precedent of the existing Medicare program. The emphasis was on universal coverage through employer mandates, and a mechanism for cost control through “managed competition” in health insurance markets; namely, government regulation of private insurers through regionally based “health alliances.” The proposal thus embraced government intervention in health care while retaining the legitimacy of private markets in health insurance.

But the Clinton compromise, aimed at forging a middle path through the public regulation of health insurance markets, failed to rally enough support from proponents of reform. At the same time, it faced considerable opposition from powerful groups with vested interests in maintaining the profitable status quo. Insurance lobbies, in particular, waged effective public campaigns against government involvement in health care. Within Congress, the administration faced opposition not only from Republican opponents but also from within the Democratic caucus. Widespread public confusion ensued, heightened by the complex details of the President’s health plan, the spectacle of warring factions on Capitol Hill, and the doomsday prophecies of its opponents. The plan finally died an ignoble death in September 1994 when, even with a Democratic majority, Senate majority leader George Mitchell was unable to ensure passage of a last-ditch compromise bill.

Much has been written about the “boomerang” effect of this health care debacle and the rise of the radical right in the United States; as the Democrats lost their majority in the Congress in the 1994 mid-term elections, Clinton would be saddled with this burden for the rest of his tenure in office, making health care reform a “no-go” zone, despite the persistent problems of cost and access. Indeed, some critics have suggested that Clinton’s welfare reform measures of 1997 worsened the health care situation, as Medicaid eligibility was transferred to the states. This would be alleviated to some extent by the introduction of the State Children’s Health Insurance Program (SCHIP), which provided matching federal funds for states to provide Medicaid coverage for children whose families did not qualify for welfare.

While the election of George W. Bush may have put the quest for universal access to care on hold, his administration gave birth to an important addition to Medicare. The Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement and Modernization Act of 2003 added prescription drug coverage to Medicare benefits, through private insurers and HMOs. A hotly debated measure, it pitted Democrats against Republicans in both houses of Congress, and turned out to be substantially more expensive to implement than had been estimated. President Bush also signed into law incentives for tax-sheltered medical savings accounts earmarked for medical expenses, which were widely criticized in the health policy community. His final legacy was the most controversial: the 2007 presidential veto of a bipartisan measure to expand the SCHIP. Since its inception, the SCHIP had spread like wildfire, extending health coverage to millions of children, and it made Medicaid the fastest growing social program in the US. This expansion would have increased spending and allowed millions more children to qualify for the program.

It was no coincidence that Barack Obama, the charismatic young senator whose bid for the Democratic presidential nomination was centred on children and families, would make SCHIP expansion a focal point of his domestic policy platform. But Obama was eclipsed on the health care front by his main rival, Senator Hillary Clinton who, despite carrying the baggage of “Hillarycare,” was determined to highlight health care on the electoral agenda.

Her efforts were helped by the deteriorating economic climate in the US, with health care costs soaring, uninsured numbers rising, and even middle-income Americans worried about being able to afford health care. Moving away from employer mandates — the hallmark of the 1993 plan — Senator Clinton focused on individual mandates that would require all Americans to be insured in one form or another.

The plan for individual mandates came out of the realization that some kind of legal obligation would have to be in place to compel universal coverage. It was also bolstered by the demonstration effect of a state-led initiative. The Massachusetts Health Care Reform Plan of 2006 has required state residents to carry health insurance, and forced employers to offer coverage to their workers or pay an assessment fee. This effort was directly aimed at reducing the number of uninsured and lowering the cost drain on the state’s health care system.

Despite the divisive primary battles among the Democratic contenders on a wide array of questions, the leading candidates — Obama and Clinton — agreed that health care required immediate attention from the federal government. Health care reform retained its high profile as Barack Obama and Joe Biden campaigned throughout the fall of 2008, and it was identified a front-burner issue for the new administration almost as soon the Obama family moved into the White House.

The twin framing of health care reform in terms of both access and cost control was a deft strategy to capture the urgency of the issue in the context of the economic crisis and, crucially, to court support from both Democrats and Republicans in the Congress. The other adroit move was to open up policy discussions and engage with stakeholders, instead of the relatively closed approach that doomed Hillary Clinton’s 1993 task force. And the attempt to inject strong leadership through the nomination of former Senate majority leader Tom Daschle was hailed as perhaps the most promising initiative of all — except that, within weeks, he was forced to withdraw due to tax irregularities.

By the time Obama took his place in the parade of presidential health reform addresses to the Congress, his message had firmed up considerably: “I am not the first president to take up this cause, but I am determined to be the last.”

Obama also tried to distance himself from Bill Clinton’s top-down approach by asking the Congress to take the lead in writing the legislation this time around. For new age management types, this may translate into strategies to “invest” partners in a change process, but in the case of controversial reform before a divided legislature, it turned out to spell old-fashioned political trouble. Without a central script, Democrats began to devise competing strategies, while Republicans and their allies, sensing a policy vacuum and a political opportunity, went to work in redefining health care reform — and the President himself — in the most negative terms possible.

By the time Obama took his place in the parade of presidential health care reform addresses to the Congress, his message had firmed up considerably: “I am not the first president to take up this cause, but I am determined to be the last.” Despite the eloquence of language and passion of delivery, Obama’s insistence on the basic elements of reform — insurance regulation, cost control measures, individual mandates — was crowded out by the deep divisions over the so-called public option. For supporters the public option is essential, because it would serve as a last-resort option for those who could not otherwise find or afford insurance coverage. For detractors, it represents, yet again, a wedge of socialized medicine, on the one hand, and unfair competition, on the other.

Here again, Canada entered the health care reform debate in the US, but this time the stakes and the situation had changed. In 1993, the single-payer model had been used by opponents and supporters of health reform alike; in 2009, the targets were much more precise and the coverage of Canada almost entirely negative. Parallels were made between the public option and the deficiencies of the Canadian public insurance systems, while infamous ads featuring a Canadian “survivor” of the system and talk radio debates over “death panels” tried to illustrate the havoc that could be wreaked by constraining consumer choice and access. Although these attacks were as misleading as in the past, they resonated more powerfully because the debate over health care on this side of the border had itself changed, leading to a noticeable erosion of confidence among some Canadians.

Regardless of whether the public option survives the journey through Capitol Hill, the stakes of health reform will continue to rise through the Obama administration’s first term in office. As different versions of health care reform bills come up for bipartisan review, the pressure toward even more compromise will intensify. Should Obama give in to this pressure, he may not be able to live up to his promise to be the “last” president to take up the health care reform cause. If the legislation that emerges from the Congress does not stress universal coverage and considerable cost control, then Obama will leave a great deal on the plate of his successors. If, however, his leadership takes the political risk of forcing a Democratic consensus to push through a vote, then he leaves himself exposed to a Republican backlash, “blue dog” alienation, and the further polarization of American party politics. He also risks, like others before him, having the health care issue become a “straw man” for a wider and deeper opposition to his political agenda.

In 1962, John F. Kennedy was adamant that health care reform was “long overdue.” A generation later, Americans are still struggling to find a workable solution for health care challenges. If the lessons of the past are a prologue to the future, it will take more than a willingness of the executive and a majority of the legislature to move forward on these controversial issues: transformative health care reform needs a powerful president, secure control of Congress, and a political climate that can attenuate partisan discord. By all accounts, the United States is not quite there yet.