Canada and the United States are staunch allies, vital economic partners, and steadfast friends. We share common values, deep links among our citizens, and deeply rooted ties. The extensive mobility of people, goods, capital, and information between our two countries has helped ensure that our societies remain open, democratic, and prosperous. To preserve and extend the benefits our close relationship has helped bring to Canadians and Americans alike, we intend to pursue a perimeter approach to security…Effective risk management should enable us to accelerate legitimate flows of people and goods into Canada and the United States and across our common border, while enhancing the physical security and economic competitiveness of our countries.

A Declaration by the Prime Minister of Canada and the President of the United States, February 4, 2011, the White House

With these uplifting words, Barack Obama and Stephen Harper punched the reset button and launched an initiative to take our long-standing economic and security partnership to a new level. The ultimate goal should be to make the flow of traffic — people, goods and services — within the single biggest bilateral trading relationship in the world as easy as that enjoyed within the European Union.

Over the coming months a series of working groups will design a new perimeter security approach that should move inspections “beyond the border.” Their guiding principles will be early threat assessment, further integration of crossborder law enforcement, cooperation around the real threat of cyber security attacks and a collaborative management of critical infrastructure — our grids, our roads, our rail and the ports that are our gateways. All of this is very encouraging.

With the expectation that “compatible approaches will lead to greater prosperity on both sides of the border,” a Regulatory Cooperation Council will be established. To placate the narrow nationalists, now found on both sides of the border, the Washington Declaration adds that the council “will in no way diminish the sovereignty of either Canada or the United States or the ability of either country to carry out its regulatory functions according to its domestic and legal policy requirements.”

It is a promising set of initiatives, although at some point the dots will need to be connected. It reflects well on Harper’s tenacity in stickhandling forward, in difficult circumstances, the eternal Canadian objective: access to the American market. The Prime Minister and President Obama may not be ideological soulmates but Obama thinks enough of Harper to carve out time and energy for the endeavour. Harper is also savvy enough to appreciate the wisdom of Brian Mulroney’s precept about the relationship that prime ministers need to forge with presidents:

This is the most important relationship, the most important responsibility that a prime minister has on his schedule. This is it, the Canada-United States relationship. If you don’t get that right, you’re going to have problems…The relationships [between prime ministers and presidents] are absolutely indispensable. If you don’t have a friendly and constructive personal relationship with the president of the United States, nothing is going to happen.

Mulroney’s remarks on February 11, delivered at Washington’s National Press Club to celebrate Ronald Reagan’s centenary, should be chiselled into the panelling of the prime minister’s Centre Block office. Bear them in mind especially when America is at war or in economic distress. Insecurity breeds isolationism and its ugly stepchild, protectionism. In either instance, Canadian interests are at risk whether by direct action or, as is more usually the case, through collateral damage.

President Obama is distracted and preoccupied by his domestic situation and the continuing high unemployment, debt and deficit that gave back control of the House of Representatives to the Republicans in the November midterms and now threatens his own re-election in 2012. Then there are the burdens of Afghanistan and Iraq, Iran and the Koreas and, of course the crisis in the Middle East, now with a new variation that has seen the ousting of Arab autocracies.

Buried within the Washington Declaration was a “Second Report to Leaders” on the 20 joint projects taking place under the Clean Energy Dialogue through working groups on carbon capture and sequestration, the electricity grid, and research and development.

Born out of President Obama’s day trip to Ottawa two years earlier in February 2009, it listed as the “key” accomplishments: “a Memorandum of Understanding to support cooperative R&D to develop materials and manufacturing processes for lightweight, energy efficient vehicles and clean energy production, a cooperative agreement to facilitate collaborative algal biofuels aimed at yielding improved productivity and harvesting methods…as well as work to develop a Clean Energy Research Development and Demonstration Framework.” After two years of “action,” when you defrost the bureaucratese, one wonders, “Where’s the beef?” Therein lies another of Harper’s challenges: turning the aspirational into actual achievements.

For skeptics, the Clean Energy update is reminiscent of those generated by the now zombified Security and Prosperity Initiative (SPP). Born at the Waco, Texas, trilateral in March 2005 with Presidents George W. Bush and Vicente Fox and Prime Minister Paul Martin, the SPP promised “new avenues of cooperation that will make our open societies safer and more secure, our businesses more competitive, and our economies more resilient.” There were also commitments to improved productivity “through regulatory cooperation” and “efficient movement of goods and people.” Three hundred action items were generated and like Mao’s thousand flowers enjoyed a brief bloom before they withered.

The February 2009 commitment for cooperation on “border management” met a similar fate. Progress was achieved on the security side — the American priority — through, for example, the Shiprider program of collaborative policing on the Great Lakes, but the Canadian ask — access — languished until Harper prodded the President during a “pull-aside” in Toronto during the July 2010 G8/20 summits.

After 9/11, authority passed from Treasury officials to Homeland Security. For them it is all about compliance and minimizing risk. For them, less traffic means less risk. The once welcoming screen door has been replaced with storm windows and increasing layers of weatherstripping.

Getting a commitment to move “beyond the border” required perseverance and presidential intervention in overcoming stubborn rearguard resistance from the Department of Homeland Security, which sees its iron rice bowl threatened. Another unhappy casualty of 9/11 was the facilitative attitude that took root after the Free Trade Agreement. Partly it was self-interest. For the Treasury officials who managed the border, more traffic meant more revenue. After 9/11, authority passed from Treasury officials to Homeland Security. For them it is all about compliance and minimizing risk. For them, less traffic means less risk. The once welcoming screen door has been replaced with storm windows and increasing layers of weatherstripping.

“Risk management” was inserted at the Canadian request into the Washington Declaration. Also back in circulation is the perimeter concept that has for so long formed the foundation of our mutual security relationship ever since Franklin Roosevelt’s 1938 declaration at Queen’s University, welcomed by Mackenzie King, that the United States “will not stand idly by if domination of Canadian soil is threatened by any other empire.” At Ogdensburg in 1940 we entrenched the concept of joint defence of “the northern half of the western hemisphere” and created the Permanent Joint Board of Defence. This approach served us for over a half century, from the Second World War through the end of the Cold War. But when the curtain came down on 9/11, the frontier shifted from the North Pole to the 49th parallel. It effectively took us out of our once durable cordon sanitaire at a time, ironically, when we were fighting “shoulder to shoulder” in Afghanistan.

FDR’s Kingston Declaration needs a 21st-century definition. A collaborative “neighbourhood watch” that goes beyond the air defence of NORAD and includes maritime interoperability as well as law enforcement and intelligence sharing makes sense. Much of this sharing already takes place — the “four and five eyes intelligence,” passenger manifest lists between Homeland Security and Public Safety, watch lists between the RCMP and FBI — but it will require both precision and care in its management and investments in new technology by the Canadian side.

Civil libertarians on both sides of the border are watchful. They are right to be so given some of the excesses (such as Maher Arar) and over-reaction by overzealous security authorities in the immediate wake of 9/11. Yet as we know all too well, from the Toronto 18 plot, there are real and present dangers that require joint collaboration in monitoring homegrown threats.

We’ll preserve our separate migration regimes, including different visa practices. But the Americans will insist on biometrics. This is the recommendation of the 9/11 Commission and they are adamant. We’ve already recognized its utility in the Smart Border Accord, and to avoid Charter challenges we should stick to the voluntary approach in return for a “fast pass” through the border. Those who don’t want to provide a retinal scan and fingerprints will have to accept the greater likelihood of delays and interrogation. As Ambassador Gary Doer reminds us, the Canadian Charter of Rights does not apply to those crossing into the United States.

Progress on the security front is essential if we are to persuade the Americans to lift their increasingly reinforced border shield. In return, we must have assured access for people and goods. The interruption of just-in-time delivery is affecting investment decisions. Coupled with our petrodollar, the Canadian advantages begin to diminish. The area of discussion that offers the most promise is regulatory compatibility. The Mexicans and Europeans are already ahead of us in their negotiations with the Americans.

Rules and regulations, the preserve of the bean-counters, have become a major barrier to trade, imposing costs of between $15 and $20 billion a year on Canadian exporters, observed Derek Burney (Policy Options, April 2009). There are over 200 separate regulations, slightly more on the Canadian side, afflicting transborder trade. Each year, regulators in both Canada and the US make an estimated 5,000 changes that further confuse and complicate life for those who would export. The difference in the standards leads to separate production runs, less efficient trade and higher costs for producers and for consumers. The transaction costs, says economist Patrick Grady, have resulted in a 12.5 percent decline in the export of goods.

Economist Katie MacMillan observes that fortified orange juice is classified as a drug in Canada but as a food product in the United States. The fortified Cheerios enjoyed by Ambassador David Jacobson for his breakfast must be produced with slightly different compositions in each of our two countries. Yet “not once have I felt less healthy” says Jacobson, the US ambassador to Canada.

For Canada, with nearly half our GDP dependent on our ability to trade, these differences constitute a commercial deterrent. Michael Hart, the former trade negotiator who holds the Simon Reisman Chair at Carleton University, argues that it is time to take a blowtorch to the “narcissism of small differences.” He offers this sensible test for regulators:

- Have you talked to the other side?

- Can you justify the differences?

- What efforts are you making to reduce these differences?

Stewardship of our economic interests also argues for greater cooperation in managing the arteries of our economic success. Let us further open our skies and roads. Let us also take the example of the St. Lawrence Seaway Authority to stewardship of our gateways, rail and road links, ports and pipelines, and the grids that power our homes and industry.

For over a century we’ve also taken a continental approach to our “commons” — the International Joint Commission is an international model for sensible transboundary water management. Building on this model we cleaned up the Great Lakes and rid our skies of acid rain. Climate reform and management of the Arctic is the logical next step in environmental stewardship. Experience with joint bi-national or bilateral institutions has demonstrated that when they manage the process, we level the playing field. By taking it out of the political arena, there is also less risk of faddism and small-mindedness in decision-making.

Probably the biggest difference between 1984 and 2011 is the acceptance by Canadians that freer trade works to our advantage. In 198485, opinion was sharply divided. Brian Mulroney had been elected leader by taking the traditional Conservative approach in opposing free trade before deciding to take the free trade “leap of faith” proposed by Donald Macdonald in his landmark 1985 royal commission report on Canada’s economic union and prospects. About a quarter of Canadians were favourable to the idea and the same number were opposed. The majority recognized that the status quo — increasing American protectionism coupled with structural economic deficiencies including deficits and unemployment — wasn’t serving our interests. There were doubts about the American willingness to truly “level the playing field,” about our ability to compete internationally, and about our capacity to preserve our independence.

After a couple of years of adjustment, we proved that we could compete internationally. A decade of trade-driven prosperity persuaded the provincial premiers of the merits of free trade, and the Chrétien Liberals came around after some cosmetic changes in NAFTA. As a result of program reviews, deregulation and an attitudinal change to deficits, Canada is now the poster child for “prudent” and responsible government. Where once (1995) the Wall Street Journal considered us an “honorary member of the Third World” it now writes (2010) that the rest of our G8 partners are looking to “reproduce the Canadian economic miracle.”

The domestic debate is not likely to be nearly as politically contentious this time as it was in the 1988 free trade election. The first survey taken after the Washington meeting by Harris Decima, indicated that Canadians overwhelmingly favour cooperation with the United States to increase border security and ease obstacles to cross-border trade, with 75 percent of respondents supporting shared intelligence gathering, 84 percent supporting harmonizing food-safety regulations and 70 percent favouring the creation of a bilateral agency to oversee the building of new border infrastructure. Nik Nanos reports similar levels of support in this special issue of Policy Options.

If Canadians have faith in the next leap forward, can the same be said of the Americans? Harper can play a mean tune but will Obama sing along? The President knows that his re-election will hinge on his capacity to create jobs. Notwithstanding Obama’s embrace of India and overtures to China, Americans’ largest market, whether they know it or not, is Canada. Supply change dynamics mean that if he is to “double American exports,” then Canada must figure in the equation.

If there was a discordant note in Washington it was on the relative worth of jobs generated by America’s trade with Canada: the President said 1.7 million while the Prime Minister claimed 8 million.

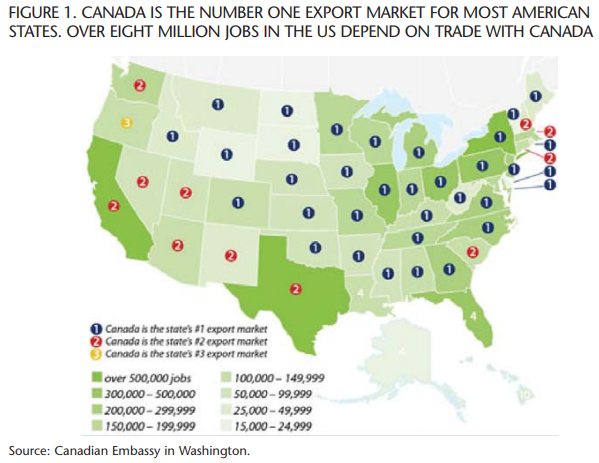

We need to share with the White House a recent study, U.S.-Canada Trade and U.S. State-Level Production and Employment (2010). Authors Laura M. Baughman and Joseph Francois conclude that in 2008, 8 million US jobs, or 4.4 percent of total US employment, depended on trade with Canada (table 1). Every US state registers net job gains from trade with Canada. This is good, non-flaky economic analysis based on US Bureau of Economic Analysis and Department of Labor data that, with the Embassy-produced map detailing trade by state with Canada (figure 1), should be shared with every American legislator and chamber of commerce.

Ronald Reagan’s vision was of a “common market from the Yukon to the Yucatan.” His persuasiveness and determination brought along both his administration and a divided Congress. It helped immensely that he liked both Canada and Brian Mulroney. The tone at the top made the difference. President Obama told us that he “loves this country” when he made his first trip to Ottawa. Now we will find out how much.

Obama must convince Congress that Canadians can be trusted and that including us in the American security blanket serves US national security and economic interests. Differentiating between the northern and southern borders, while avoiding a reopening of the immigration debate, will take skill and finesse. Just as we took a whack-a-mole approach to recurring mythology about the 9/11 terrorists coming in from Canada, so we need to take a similar approach to the pronouncements on the perils of the northern border from Senator Joe Lieberman and others.

There should also be eventual provision for Mexico. Demography is destiny and the American mosaic is changing. We need to be ahead of this trend by reaching out to Mexico. There are now more Americans with Latino roots than there are Canadians.

The Canadian debate will be noisy. The kabuki-like foreplay — with endorsements by our business sector former Canadian and American ambassadors and former PM Mulroney — plays to populist arguments about a secret corporatist agenda. Concerns over privacy, standards and sovereignty need to be assuaged and the case made for how the initiative serves the national interest. We also need to learn to differentiate between noise (i.e., to not get upset about every congressional bill that is going nowhere) and substance.

A deal will also oblige both sides to clear up unfinished business. The Obama administration owes us the XL pipeline waiver. The Canadian parliament needs to make the necessary changes to secure passage of copyright protection legislation to get us off the blacklists of both the US and the EU.

Critics on both sides will rag the puck, mindful that political will is a finite commodity, especially for governments facing elections. The public in both countries is skeptical and increasingly defiant toward negotiations by stealth. Complementary and compelling narratives around jobs, growth and security need to be developed. Canadian business and labour will need to step up to the plate. They need to remind their head offices, customers and affiliates that continental supply chain dynamics work to their advantage.

Process will be critical given election pressures. The best model is that of the Manley-Ridge Smart Border Accord (2001). Tom Ridge, the former governor of Pennsylvania, and John Manley, the jack of all cabinet portfolios, were both pragmatic doers and determined on results. The Accord focused on 30 recommendations. It established dead-lines and joint accountabilities, obliging officials to deliver results or define the problem and offer solutions for political decision. The Internet was used to show progress and demonstrate transparency. It worked.

Harper needs to confide in Liberal leader Michael Ignatieff and the premiers. Success will be more likely if we can make this a united front of our two major parties. Ignatieff gets it. As he blogged on the eve of President Obama’s 2009 visit, “We can either complain about unsolved problems or seize the opportunity to excite him with the possibilities of partnership.” Some in his caucus are burdened with a reflexive anti-Americanism but most of his senior team are not. The government should show the cooperative spirit that was demonstrated by the two parties in deciding to stay on in Afghanistan.

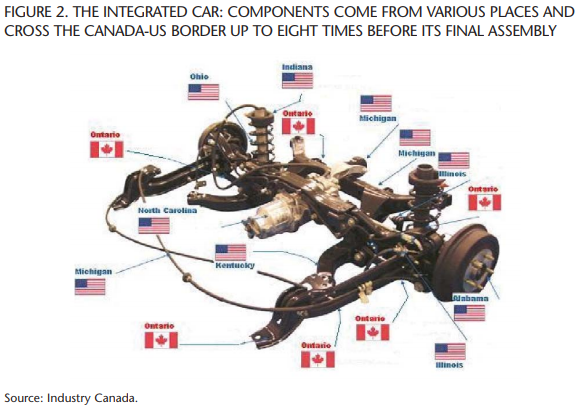

Last year’s agreement on procurement reciprocity demonstrated the value of our premiers reaching out to their governor counterparts. As chair of the Council of the Federation, Saskatchewan’s Brad Wall developed a united front that the premiers advanced at the February 2010 National Governors’ Association in Washington and in regional and bilateral meetings. They pointed out that we don’t so much trade as make things together and that working together improves our relative competitiveness. The recovery of the auto industry is a case in point, especially when you realize production involves multiple criss-crossing of the border (figure 2).

Importantly, the reciprocity agreement also demonstrated that in Ambassadors Doer and Jacobson we have first-rate envoys who have quickly learned the diplomatic game. Jacobson is a problem solver and possesses a Rolodex of the key players in Washington, many of whom he knows from his time in the White House appointments office. As Manitoba premier, Gary Doer cultivated his American counterparts and encouraged his fellow premiers to follow suit. He demonstrated the difference that additional voices in common cause can make in the American political system. As ambassador, he has lampooned the “frozen facts” of the oil sands critics and capitalized on his experience as a labour negotiator to build relationships with the American unions.

Taking the Canada-US partnership to the next level makes sense. Nor do we really have a choice. Sticking with the status quo means continuing incremental decline. It will require leadership, time and money as well as follow-through to ensure actions follow words. In the meantime, the global express is picking up speed.

Photo: Shutterstock