Discussions about the Canada-Asia energy relationship are often divisive and polarized. We lack a strategic framework for Canada’s energy relationship with Asia, one that attempts to bring together often conflicting facts and certainly diverse views. Such a framework should aim to situate this energy relationship within the broader context of Canada-Asia relations and Canada’s national interest. From our perspective, this energy relationship cannot be separated from the broader political, economic and social relationships between Canada and Asia.

Canada has a medium-sized economy that is dependent on international trade, and its prosperity is inextricably linked to external markets and the ability to access these markets. For much of the postwar period, Canadian industry could rely on the United States as the overwhelming source of demand for its commodities, goods, and services. Reliance on the American market was further increased with the signing of the Canada-US Free Trade Agreement in 1988 and the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) in 1994. The gravitational pull of the US economy was a sound business reason for Canadian companies to focus their attention on the American market. Over the years, the infrastructure of Canada-US trade — including energy, transportation, institutions, people-to-people ties and legal frameworks — has deepened to the point where north-south trade has become the norm.

The decades-long focus of Canadian industry on North American markets has, until recently, meant the general neglect of other markets. Government and business leaders now recognize the importance of diversifying Canada’s commercial activities to take advantage of explosive growth in developing countries, particularly in the so-called emerging markets. If there was any doubt about the importance of emerging markets, the “great recession” of 2008 underscored the shift in global economic weight away from the West. Canada was spared a more severe recession in 2009, in part because of robust demand from Asia — especially China — for our natural resources. Indeed, in the three years following the recession, emerging markets accounted for over 75 percent of global growth.

For many industries in Canada, exporting to Asia is an entirely new activity, and that is as true for resource industries as it is for manufacturing and service industries, but it is particularly so for the energy sector. The reason is pretty basic: the American market has long been the destination of choice for most Canadian exports: close to 75 percent of Canada’s total 2010 exports went to the United States. Nowhere is our trade dependency on the United States more evident than in energy — particularly oil, natural gas and electricity. While Canadian coal exports have long gone to Asia, and Canadian firms have built effective supply chains in the region, the situation is dramatically different for oil and natural gas.

The gravitational pull of the US economy was a sound business reason for Canadian companies to focus their attention on the American market. Over the years, the infrastructure of Canada- US trade — including energy, transportation, institutions, people-to-people ties and legal frameworks — has deepened to the point where north-south trade has become the norm.

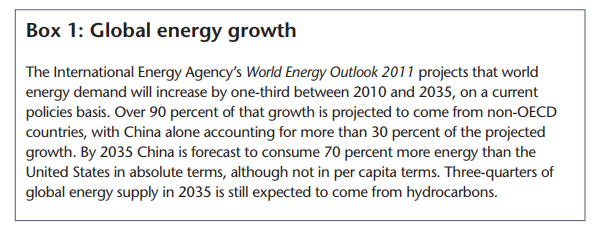

As table 1 shows, Canada’s natural gas and crude oil exports go almost exclusively to the US, as do all hydro-power exports. Despite the occasional storm that rocks the boat, Canada’s trade relationship with the US has been amicable, resulting in an integrated North American energy system where Canada plays an important role in American energy security as its largest supplier of crude oil and natural gas.

For an energy exporting country with abundant natural resources, our biggest challenge is security of international demand for our resources, and at the best possible prices for our products. This sets us apart from the United States and other G7 countries which are primarily concerned with security of energy supply, and at the lowest prices possible.

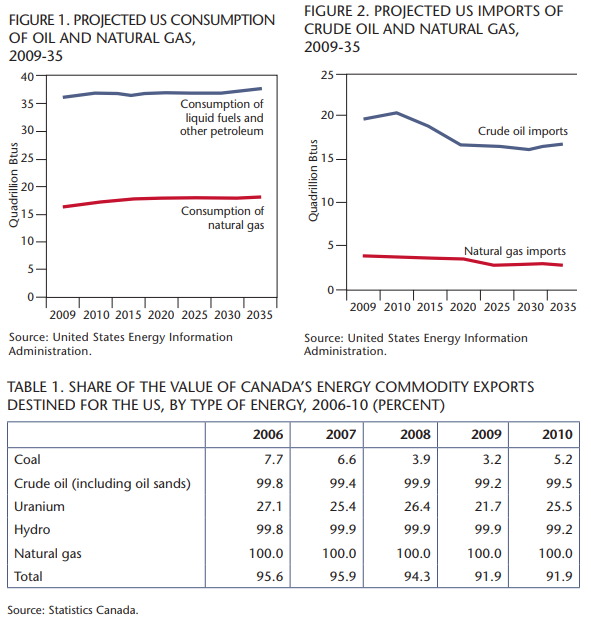

This almost total reliance on a single customer for our oil and natural gas exports, albeit still the largest economy and energy consumer in the world, is not without risk to a trading economy. As the old cliché goes, when the American economy sneezes, Canada catches a cold. More fundamentally, basic economics suggest you seldom maximize the value of what you are selling when there is only one buyer for your products. The trade risks, however, go well beyond sporadic economic downturns and our demonstrated capacity to weather cyclical variation. American energy forecasts show flat demand over the next 25 years. The most recent projections of the US Energy Information Administration, for example, predict little to no growth in oil and natural gas consumption (see figure 1).

The picture grows more discouraging for Canadian producers if we look beyond aggregate demand to projections for American imports. Not only is the American energy demand pie staying the same size, its share of the global pie is shrinking. Both crude oil and natural gas imports are expected to decline over the next two decades as demand is tempered and domestic supply increases (see figure 2). Unconventional gas and oil discoveries in the United States have increased the prospects for greater energy independence, and the Keystone XL pipeline dispute illustrates growing market access issues for Canadian producers. Canada, therefore, is locked into a market that is slow growing, intensely competitive and fraught with political pressures.

If the future of Canada’s energy sector is dependent on security of demand, then market diversification is imperative. American markets will always remain an important part of Canada’s energy future.

However, our traditional reliance on those markets will not provide adequate security in light of the projected decline in US import demand for oil and natural gas, and public resistance to the importation of Canadian oil.

Without security of demand, the Canadian industry will not be able to invest in the long-term projects that create jobs and generate wealth. And, the Canadian oil and gas industry will continue to suffer from a price discount relative to world prices if it cannot sell into other markets. This strongly suggests that growth in the Canadian energy economy will depend on market diversification. The primary opportunities for Canada’s energy diversification are to be found in Asia; and the primary beneficiaries of such diversification will be Canadians.

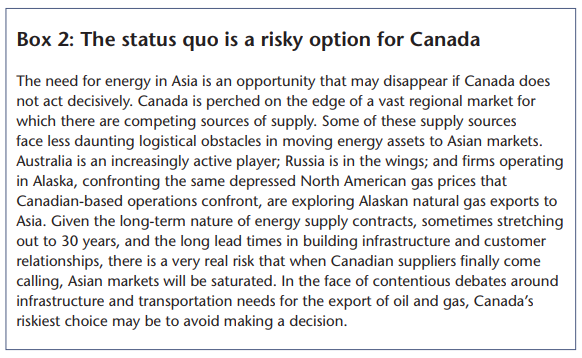

Diversification would provide an excellent opportunity for Canada to align its abundant energy resources and expertise with rapidly growing demand from Asia. Global energy demand growth will not be limited to Asia, but Canadian prospects for market diversification beyond Asia are limited. Although the Canadian government has acted aggressively to expand Canada’s trade ties with Europe and Latin America, potential global energy markets are more limited in scope than are the potential markets for manufactured and agricultural exports. Shipping energy resources to South America, Russia, the Middle East or Africa would be akin to shipping coal to Newcastle, and the European Union poses significant logistical and market access challenges for Canadian energy. At the same time, we need to recognize that other countries, particularly Australia, are also aggressively pursuing Asian markets as a source of growth for their energy exports.

Another advantage of diversification for Canada would be the impact on the oil and gas price discounts that Canadian exports face in today’s over-supplied regional US markets. The spread between the price of imported natural gas in Japan and the spot price at Henry Hub, Louisiana, is significant, ranging well above $10 in recent years. This large price-arbitrage potential would bring billions of dollars of additional income to Canada, given our daily gas production potential, if we had access to Asian markets for our gas.

Another advantage of diversification for Canada would be the impact on the oil and gas price discounts that Canadian exports face in today’s over-supplied regional US markets. The spread between the price of imported natural gas in Japan and the spot price at Henry Hub, Louisiana, is significant, ranging well above $10 in recent years. This large price-arbitrage potential would bring billions of dollars of additional income to Canada.

A similar price differential exists for Canadian crude oil. For many reasons — the infrastructure bottleneck at Cushing, Oklahoma (causing inventories of crude to rise), inadequate pipeline access to Gulf Coast refineries, no access to West Coast refineries and lack of access to Asian markets — Canadian crude faces a significant discount relative to world prices. One study projects the discount between Western Canadian sweet crude oil and West Texas intermediate crude oil at $27 a barrel by 2014. In their 2011 study, Moore et al. estimated that with improved Gulf Coast, West Coast and Asian access for crude oil, Canada would see an increase of $132 billion in GDP (in current dollars), spread over a 15-year period.

Canada is very much on the global energy radar, not just as a potential supplier but in many respects as a preferred choice over other suppliers in troubled parts of the world. Energy security has been a preoccupation of major Asian economies since the oil shocks of the 1970s, but with the dramatic rise in overall energy demand in the region, principally led by China, the quest for secure, long-term sources of oil and gas has become more acute. Recent developments, such as the Fukushima nuclear disaster in Japan and geological risks in the Straits of Hormuz, have added to the urgency of energy security in Asian countries. At the same time, the determination of Asian countries to become more energy efficient and less reliant on fossil fuels presents an opportunity for Canada’s energy relationship with Asia to include cooperation on clean energy, energy efficiency and environmental protection in the energy sector.

In short, this suggests that there is clear strategic alignment between Canada’s interest in security of energy demand and Asia’s quest for security of energy supply. The current misalignment can be seen most vividly in the price differentials that exist between North American and Asia oil and gas markets, which present an immediate opportunity for trans-Pacific oil and gas exports from Canada. Alignment of Canadian and Asian energy interests, however, should extend to all forms of energy, drawing on the diversity of energy assets and expertise across the country.

The magnitude of the energy opportunity in Asia for Canada, the scope of its potential impact across many industries and regions of the country, and the breadth of possible economic and social benefits for all Canadians lead us to an inescapable conclusion: the full potential of the Canada-Asia energy relationship cannot be realized on a project-by-project, enterprise-by-enterprise basis. There is truly a national interest in pursuing a broad-based Canada-Asia energy framework, and hence an urgent need for national leadership.

Simply put, resources without markets, or without the transportation infrastructure linking resource developments to those markets, have little economic value. The economic value of our resources increases with market and transportation infrastructure development. Canada will require a diverse array of infrastructure in order to export energy to Asia.

Prime Minister Stephen Harper has made clear his determination to diversify Canada’s trade toward Asia, with a focus on exports of Canadian energy products. However, it is less clear how this will come about, or if the efforts of individual provinces, firms and projects will in and of themselves amount to the kind of broad-based energy relationship with Asia that will generate the scale of potential benefits for the country as a whole. Indeed, it is conceivable that oil and gas export projects could fall victim to economically damaging delays if stakeholders do not have a shared vision of the Canada-Asia energy relationship that demonstrates the distribution of benefits across a wider spectrum of interests across the country.

Hence, the importance of developing a strategic framework for the Canada-Asia energy relationship, one that engages the broader national interest. The onus should be on the private sector and governments, both federal and provincial, together with First Nations leaders and environmental interests, to coalesce around such a framework and, over a timeframe that recognizes the urgency, to act to capture this opportunity. Such a strategic framework should consider the following elements:

Think “big” on diversification: Diversification into significantly new and different markets and geographies works best on a significant scale and scope: in short, think “big” on diversification. Canada needs to develop the capacity to export energy to Asia, which is home to the most rapidly growing markets for energy products. However, diversification is not simply about exporting to new markets. If Canada is to maximize its future prosperity, Canadian governments and industry should ensure that in their relationships with Asia they are not overly focused on one country, product, industry or technology. A major focus of this diversification strategy should be to emphasize innovation and value added production — which means going downstream on energy products and services to the greatest extent possible and economically feasible, including greater emphasis on innovation in the conventional and alternative energy sectors.

Country diversification: As the world’s fastest growing economy, China must be a priority market for Canada’s energy products. However, China is not the only Asian country that will require substantial energy resources in the future. Diversification should mean selling energy products and services to multiple buyers in multiple countries, thereby strengthening Canada’s security of demand. Japan, for example, will require imports of natural gas as it shifts heavily away from nuclear power production following the Fukushima nuclear disaster. Korea is already a major importer of natural gas and uranium, and it should be another priority market for our energy exports. India is a more distant market for Canadian oil and gas exports, but there is good potential there for the sale of uranium and nuclear expertise, subject to final arrangements under the Canada-India nuclear cooperation agreement.

Product diversification: Canadian governments and industry should promote the full range of their energy commodities, expertise and renewable energy technologies in Asian markets. Asian countries will be looking to import not only oil and natural gas, but also a wide range of other energy and mineral products, such as renewable energy and green technologies. Canada’s renewable energy and green technologies sector needs access to large and fast growing Asian markets to be competitive, which in turn would support product development and innovation. Canadian energy expertise is found across the country, and extends into the financial and manufacturing heartlands of Ontario and Quebec. The Toronto Stock Exchange and the TSX Venture Exchange are already global centres for the listing of mining and energy extraction companies, as well as in the financing of energy projects. Indeed, there are emerging clusters of energy expertise across the country. The further development of Canadian energy clusters (in extraction, distribution, research, finance, manufacturing, etc.) can serve as platforms for the expansion and diversification of energy trade with Asia, based on strategies that are specific to each cluster.

Industry diversification: In the same way that energy trade with Asia should encompass a wide range of products and services from Canada’s various energy clusters, the Canadian economy as a whole must look to Asia as a key source of demand for future growth and innovation. The fact that Asia has become the most promising market for Canadian energy exports means that it is also the most promising market for other Canadian industrial sectors.

At the heart of Asia’s continuing rapid economic rise — and hence the growing need for energy and other resources — is the dramatic increase in its middle class (estimated in the range of 600-900 million people) and its need for massive investments in infrastructure. These two forces are creating new sources of demand for products and services across a range of industries that Canada can, and should, capitalize on. What these newly emergent consumers want — whether it is better and more sophisticated nutrition for their families, better housing, better education, better health services, better financial services, and better entertainment services (including tourism) — represents enormous opportunities for Canadian companies, including small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs).

To achieve the objective of greater SME involvement in the opportunities in Asia, consideration should be given to a more specific trade development focus for Asia in the form of new public-private trade development partnerships to help Canadian firms, including energy companies, trade successfully there. These partnerships would create critical mass in information sharing and market knowledge among Canadian enterprises interested in exploring Asia opportunities. The partnerships should also include industry groups such as boards of trade, chambers of commerce, and universities and community colleges. Critical to sustained success is the training of the current and next generation of Canadian business leaders to do business in Asia.

Diversification through innovation: If Canada aspires to be an energy powerhouse over the long term, it must become an innovation powerhouse in energy — unconventional oil and gas exploration, development and production, renewable energy development, hydro power, distribution, logistics and conservation. We need to be innovating in the energy products and services we sell, the processes by which we produce and distribute them, and the markets into which we sell them. But Canada suffers from too little investment in research and innovation today in all sectors, including energy. In fact, as Kevin Lynch and Munir A. Sheikh demonstrated in the September 2011 issue of Policy Options, Canadian private sector spending on research and development (R&D) ranks 20th among OECD countries.

The full potential of the Canada-Asia energy relationship cannot be realized on a project-by-project, enterprise-by- enterprise basis. There is truly a national interest in pursuing a broad-based Canada-Asia energy framework, and hence an urgent need for national leadership.

What will it take to achieve this? Building on the large investments in Canada’s university research capacity by both federal and provincial governments over the past 15 years, governments and the private sector should commit to establishing world class centres of excellence in energy research and technology, matched to Canada’s energy strengths, at a scale, scope and level of excellence that would place Canada at the global forefront of key aspects of energy research and innovation. A network of energy innovation institutes would foster close university/ industry/government investment and collaboration on research and problem-solving, and have the compelling mandate of making Canada a recognized global leader in efficient energy production, including value-added energy products and energy solutions.

The need for leadership: An expanded Canada-Asia energy relationship has the potential to provide substantial benefit to Canadians all across the country, provided we think creatively about the potential markets and benefits. However, the development of this relationship will involve many different jurisdictions, corporations, and civil society groups that have a heterogeneous set of interests. Parties affected by specific projects or proposals will legitimately take the perspective of their specific and sometimes narrow interest, as defined by the community, organization, or government that they represent.

The federal government uniquely has the opportunity of defining and advocating for the national interest. The building of the Canada-Asia energy relationship should be considered a national endeavour that would generate benefits for all parts of the country. But crafting such a vision will also require leadership from stakeholder groups across the country, in particular provincial governments, business, First Nations governments, and environmental and other civil society organizations. To quote from our earlier commentary in the February 2012 issue of Policy Options:

Energy is the lifeblood of every economy and society around the world. But there are inevitable linkages and trade-offs among economic growth, energy use, environmental stewardship and standard of living objectives. The challenge is to address these trade-offs, not to be stymied by them, and to do so in an inclusive, analytic and realistic manner with the clear goal of improving the long-term prospects of Canada and Canadians. The role for industry, governments, environmentalists, Aboriginal groups and citizens is to engage together to find those positive compromises, and this takes leadership.

The federal government is the obvious leader to develop a framework for the Canada-Asia energy relationship. The framework should be based on the fundamental need for closer economic ties with Asia to secure Canadian prosperity; diversification of markets to protect Canada’s security of demand; and a broad definition of energy that includes fossil fuels, renewables, clean technology and expertise. By focusing on market fundamentals and the benefits of expanding the scope of the opportunity, there is a better chance the federal government will be able to shape a framework that accommodates the interests of commercially motivated firms, provincial governments and First Nations that are affected, and is also able to win the support of the general public.

More generally, the federal government has an inescapable role in developing the linkages between Canadian resources and Asian markets. Its constitutional responsibilities for international trade, ports, fisheries and oceans, navigable rivers, and for Aboriginal affairs, along with its concurrent powers relating to environmental stewardship, are obvious. The federal and provincial governments will need to co-operate to continue to develop streamlined regulatory processes that provide the required level of standards and scrutiny and to create more efficient and effective energy project approval processes. The federal government will also have an important role in encouraging cooperation and collaboration among the various interests, including First Nations, provinces, private sector concerns and other stakeholders. Indeed, without the federal government as an active player at the table, negotiating the inevitable trade-offs in project development and securing the social license to operate will be difficult if not impossible.

A broad-based framework for Canada-Asia energy relations should articulate the benefits of energy exports for all parts of the country, not simply for the oil and gas-rich western provinces, and this will require leadership from various provincial governments. To be sure, development of the oil sands in Alberta creates economic activity well beyond that province’s borders, which in itself makes oil sands development of national import. Alberta must more clearly articulate the benefits of oil sands development for the rest of the country and provide leadership in the formulation of a Canada-Asia energy framework that explicitly includes renewable and clean technology. British Columbia should step up on the issue of energy transportation infrastructure to the west coast. BC can also use its jurisdiction over resource use to advance discussions with First Nations governments on Strategic Land Use Agreements, such as the one concluded with the Haida. Saskatchewan is an energy-rich province that has interests in uranium as well as oil, and Asian markets already account for a large share of Saskatchewan exports.

Business must also play a leadership role in the articulation of this intersection between private interests and the national interest. The current state of industry-stakeholder relations on a number of proposed Canadian energy export initiatives is somewhat troubled. Business has a clear interest in helping shift the public policy question on transporting energy to Asia from whether it should happen, to which options are best. More specifically, they have a responsibility to better address the perceived risks that are associated with their projects, which in turn would make it easier for governments to demonstrate the national interest in supporting these projects. More attention should also be given to mitigation plans and insurance schemes, rather than mere assurances of safety.

Many First Nations governments are looking to develop business ties with Asian partners in all sectors, including in the energy sector. While no community will have the same approach to development, First Nations governments generally seek to be a partner with the federal government, the provincial governments involved and industry to develop energy assets in First Nations lands.

Naturally, provincial and federal governments, industry and First Nations governments will not always agree, including on the role that First Nations should play in energy development. However, the realities suggest that the risks and benefits of major energy projects that affect First Nations’ communities will have to be shared amongst federal and provincial governments, the First Nations involved, and industry. Government and industry can improve the chances of energy projects succeeding by engaging early and often with First Nations communities and governments. Clearly, the rights of First Nations across Canada must be respected and protected, and the courts have ruled that consultation (and in some cases accommodation) is the legal responsibility of governments. Nonetheless, a positive relationship between a company and a First Nations government is often an important component in gaining the “social licence” to successfully undertake a project.

Environmental groups and many First Nations have expressed concerns about the potential environmental impacts of the new infrastructure required to enable oil and natural gas exports to Asia, as well as shipping in coastal waters. Such concerns about environmental risks and remediation capacity, and more generally about responsible and sustainable development, deserve discussion and consideration.

There is a real and pressing need for leadership from environmental groups and First Nations governments to propose ideas, including on least harmful options for the export of oil and gas to Asia, and to participate in the crafting of a Canada-Asia energy framework. Government, industry, First Nations governments, and environmental groups have a responsibility to Canadians to work together to find solutions to concurrently safeguard our economic prosperity and our environmental well-being.

A consultative voice on the Canada-Asia relationship: Canada’s deep trade and investment links with the United States have grown up over more than a century, particularly in the 65 years since the end of the Second World War. These links reflect shared experiences in war and peace, commercial opportunity, north-south infrastructure (highways, seaways, air connections, pipelines), educational partnerships, bilateral agreements (e.g., the Auto Pact, North American Aerospace Defense Command, environmental agreements and the Free Trade Agreement), as well as extensive people connections. In pursuit of diversification of our trade and investment towards Asia, little of this “infrastructure” is in place, nor do we have the luxury of a half century or more to develop it.

In all this, our risk may be national complacency, and our riskiest choice may be the status quo. Canada’s energy approach should be more clearly based on our national interest, not a collection of private interests. The national interest should be centred on ensuring Canadian firms are competitive in global markets while able to pay rising wages for employees and support increasing standards of living for Canadians.

To fast track the deepening of the relationship between Canada and the key countries of Asia, we believe consideration should be given to establishing a Canada council on Asia that would bring together Canadian and Asian leaders in business, academia, civil society and politics to provide wise counsel to the Government of Canada and Canadians on the objective of diversification towards Asia in all its dimensions. Such a council should be chaired by the prime minister, denoting the national interest in the exercise, and could be supported by a mixed secretariat comprising the Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade, the Canadian Council of Chief Executives and the Asia Pacific Foundation of Canada. It should consist equally of members from Asia and Canada, should meet more than annually, and should provide wise counsel to the government and Canadians.

Commitment to developing the necessary infrastructure to export energy to Asia: Simply put, resources without markets, or without the transportation infrastructure linking resource developments to those markets, have little economic value. The economic value of our resources increases with market and transportation infrastructure development. Canada will require a diverse array of infrastructure in order to export energy to Asia.

While oil pipelines from Alberta to the west coast are currently attracting public attention, it is important to recognize that infrastructure is required for the export of all kinds of products. A commitment to developing infrastructure for exports is a prerequisite for closer economic ties with Asia and a diversification strategy that enhances Canada’s security of demand. The Asia Pacific Gateway and Corridor Initiative is an example of infrastructure investment that enhanced the competitiveness of Canadian ports and airports to transport goods and people across the Pacific. Like this initiative, a Canada-Asia energy framework should have infrastructure investment as an essential feature for energy trade with Asia to take place.

Whatever the form of infrastructure investment required, it is essential that stakeholder interests are balanced, so that projects can proceed expeditiously. Government and industry should encourage an airing of all potential infrastructure options for exporting energy to Asia, including pipelines and rail, so that they can be discussed and considered in the development of a Canada-Asia energy framework.

One idea that may merit further study is a public energy transportation corridor that is constituted by government, regulated as a kind of public utility and operated by the private sector. This corridor could be some combination of pipelines and rail transportation for oil and gas to the west coast. Governments would have responsibility for setting and enforcing environmental, safety, and other standards. They would consult with involved First Nations on environmental safeguards and possible models for revenue-sharing with operations in the corridor. Environmental groups would be consulted with respect to standards and the appropriate remediation capacity. The private sector operators would in turn operate under the terms of the negotiated agreements, and they could be selected through open requests for proposals. In this way, the onus to come to terms with the multiple interests that are affected by transportation corridors will rest with more than private sector companies, reflecting the national interest imperative.

Why a public energy transportation corridor? Equally, one could ask why a St. Lawrence Seaway, a TransCanada highway system, or a national ports and airports system? Simply put, when do the external benefits of collective action outweigh individual interests and concerns, and how can one construct the collective action framework in a way that it minimizes risks, maximizes public gains and appropriately shares the benefits of invoking the national interest?

In conclusion, we believe that the potential benefits to Canadians from diversifying our trade toward Asia are enormous, but they are accompanied by real and perceived risks that may be better addressed through collective action, rather than a series of uncoordinated private sector initiatives. It is impossible to imagine a sustainable economic future for Canada without a much broader and deeper relationship with Asia. As the global centre of economic gravity shifts toward Asia, Canada will need to diversify its trade and investment linkages to ensure that we are benefiting from the massive opportunities these new markets offer.

The potential of Canadian trade with Asia extends well beyond the energy sector, and can include virtually every aspect of the Canadian economy. Nonetheless, energy trade is the strongest card we have to play in our fledgling economic and political relationship with Asia. Energy industries, broadly defined, are central to the Canadian economy, and the potential for export of energy commodities and expertise is immense. The competition to meet Asia’s voracious demand for energy is fierce, and first-mover advantages make it very difficult for latecomers to have a viable business case.

In all this, our risk may be our national complacency, and our riskiest choice may be the status quo. Canada’s energy approach should be more clearly based on our national interest, not a collection of private interests. The national interest should be centred on ensuring Canadian firms are competitive in global markets while able to pay rising wages for employees and support increasing standards of living for Canadians. This means we have to be more clever hewers of wood and smarter drawers of water, and part of this innovation should be diversifying into new markets and new consumers in Asia.

There is considerable urgency in forging Canada-Asia energy trade, and the starting point should be the establishment of a Canada-Asia energy framework that assembles the diverse energy interests across the country around a common purpose. The current project-by-project approach has become contentious and could become more so. We believe what is needed is a fresh statement of the national interest in building a CanadaAsia energy relationship, and leadership to make it a reality.

This paper draws on the report of the Canada-Asia Energy Futures Task Force established by the Asia Pacific Foundation and the Canada West Foundation in the fall of 2011, and co-chaired by Kevin Lynch and Kathy Sendall. The report, entitled “Securing Canada’s Energy Future,” can be accessed at www.asiapacific.ca

Photo: Shutterstock