The federal government had three pipeline options to ship Alberta’s oil to the West Coast. It cancelled one (Northern Gateway) and is in the process of shutting down another (First Nations Eagle Spirit Energy Corridor). It is left with the most challenging environmental option, the expansion of the Trans Mountain pipeline to Vancouver.

The government has put all of its eggs in the Trans Mountain basket (it now owns it). Although the National Energy Board (NEB) has approved the Trans Mountain expansion for the second time, the project is meeting stiff opposition from environmentalists, the cities of Burnaby and Vancouver, and coastal First Nations. The government is currently engaged in court-ordered consultations, and it is facing a BC government court challenge.

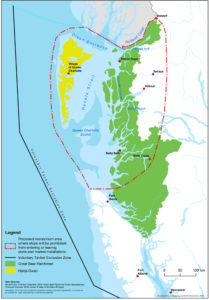

In the meantime, the government is actively pursuing Senate passage of Bill C-48, the West Coast Oil Tanker Moratorium Act. Peter Harder, Government Representative in the Senate, says the act will simply enshrine in law “the longstanding moratorium on bulk shipments of crude oil along the northern coast of BC.” But there is no such moratorium: there is, however, a tanker corridor that (voluntarily) keeps Alaskan tankers 100 nautical miles off the BC coast. It has nothing to do with BC’s northern coast, which is where the new legislation would apply.

If Bill C-48 proceeds, it will put an end to the Eagle Spirit Energy Corridor, which would run from the oil sands across Indigenous lands to BC’s northern coast, along with Indigenous peoples’ hopes for a better economic future.

In 2002, Calgary’s Enbridge Northern Gateway began feasibility studies and public consultations on a pipeline from the oil sands to a west coast terminal, which was to ship Alberta crude to Asian refineries and markets. Four years later, the federal Minister of the Environment appointed an independent review panel to work with the NEB to assess the Northern Gateway proposal.

The panel heard from hundreds of participants in 21 communities, including First Nations; reviewed 175,000 pages of evidence; and received 9,000 letters. It determined that, overall, “Canada and Canadians would be better off with the Enbridge Northern Gateway than without it.” In May 2014, the Harper government accepted the panel’s recommendation to approve the proposal for pipeline and its Kitimat terminal on BC’s northern coast.

During the 2015 fall election campaign, Liberal Leader Justin Trudeau vowed to ban tankers from BC’s northern coast and to stop the Northern Gateway project. The Federal Court of Appeal ruled that the Harper government had failed to fully consult First Nations on Northern Gateway. The new government did not appeal this decision, but it passed an order-in-council to put an end to the project. The government subsequently reimbursed Enbridge $14.7 million for its regulatory fees, but offered nothing toward the company’s $373 million in lost costs.

The federal government went a step further. In May 2017, it introduced Bill C-48, a law that would ban tankers carrying crude oil from stopping or unloading at ports along the BC coast between Alaska and the northern tip of Vancouver Island, as well as at Haida Gwaii. (It allowed tankers to use BC’s southern ports and waters.)

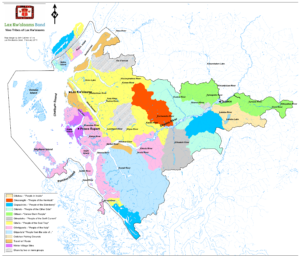

The Bill passed in the House of Commons last year and is being debated in the Senate. From the beginning, nine First Nations who see an energy corridor not as an intrusion but as an opportunity for economic development ─ a seemingly unlikely group ─ opposed the Bill. They created a chief’s council to administer the Eagle Spirit Energy Corridor company and oversee the pipeline’s construction.

To get the Bill through the Senate, the government has resorted to the gambit of saying it is putting into law what has been in place for some time. Harder told the Senate that a “moratorium on crude oil shipments along the northern BC coast has been in place since 1985, with the voluntary tanker exclusion zone. . . created in response to the completion of the Trans-Alaska Pipeline system in the early 1970s.” He said it was formalized in a 1988 agreement between the United States and the Canadian coast guard.

However, Harder did not provide all of the details. The United States first established the voluntary tanker exclusion zone in 1977, putting Alaskan tanker traffic 100 nautical miles west of Haida Gwaii. After tanker owners complained about compliance costs, the zone was cancelled in 1982. Following discussions between Canada, the US and the tanker industry, an interim tanker exclusion zone was put in place in 1985 and finalized by the two countries’ coast guards in 1988. Author Ted McDorman outlines the events in his 2009 book Salt Water Neighbors.

Harder told the Senate that Prime Minister Justin Trudeau made a commitment to Canadians “to give the crude-oil tanker moratorium the strength of law.” How can a voluntary tanker route that applies only to Alaskan tankers 100 miles off BC’s coast be called a crude-oil moratorium that applies to waters along the BC coast?

The goal of Bill C-48 is entirely new: to ban crude-oil tankers from using Canadian ports along the northern BC coast. Even the Sierra Club, in its submission in support of Bill C-48, stated the Bill would do nothing to stop existing petroleum tank barges passing by BC’s north coast in transit between Alaska and Washington State, as they do not stop at BC ports. Even the Canadian Coast Guard, in its October 6, 2017 advisory, says the exclusion zone “does not apply to tankers travelling to or from Canadian ports.”

In 1972, the federal government announced a proposed moratorium on crude oil traffic through the north coast’s Dixon Entrance, Hecate Strait and Queen Charlotte Sound off Haida Gwaii. This moratorium was never put into law for the very good reason that the US contests the status of these waters. Since the 1890s, Canada has claimed that the waters of Dixon Entrance immediately south of the Alaskan panhandle are internal waters of Canada. It has extended that claim southward to include Hecate Strait and Queen Charlotte Sound.

Under international law, Canada could only impose and enforce a tanker ban in these waters, particularly at Dixon Entrance, if they were considered internal waters of Canada, which the US opposes.

The US has sent a series of diplomatic notes over the years contesting all these claims and has even drawn boundaries for its own territorial sea in Dixon Entrance. Under international law, Canada could only impose and enforce a tanker ban in these waters, particularly at Dixon Entrance, if they were considered internal waters of Canada, which the US opposes. Bill C-48 attempts to avoid this difficulty by applying the moratorium only to ships entering or leaving Canadian ports where Canada has uncontested control.

In April 2018, the coastal Lax Kw’alaams First Nation, part of the Eagle Spirit group, filed a legal challenge against Canada and BC, asking for a court declaration that if Bill C-48 passes, it would have no effect in Lax Kw’alaams territory, which includes Grassy Point, near Prince Rupert, where a planned terminal would go. If Bill C-48 becomes law and their legal challenge fails, the Trans Mountain pipeline expansion will be the only remaining pipeline proposal to transport oil from Alberta to the west coast.

However, Trans Mountain’s Burnaby terminal, which is part of the Port of Vancouver, is not ideal as a west coast terminal. The Port of Vancouver is Canada’s busiest port. Last year, it shipped a record 142 million tons of grain, chemicals, containers, bulk goods and crude oil. Approximately 250 vessels a month use the port, but only 2 percent are oil tankers. The Trans Mountain expansion will increase the full capacity of the pipeline system from 300,000 barrels a day to 890,000 barrels a day. This would result in a seven-fold increase in the number of oil tankers using the Burnaby terminal, to around 34 per month (14 percent of total ship traffic). By comparison, the areas around Northern Gateway’s now-abandoned port at Kitimat and Eagle Spirit’s yet-to-be-developed Grassy Point terminal are relatively free of congestion.

Petroleum is by far Canada’s largest export. Over the past 10 years, oil has allowed Alberta to provide a total of $220 billion in transfers to the rest of Canada – almost three times more than Ontario. Expanding Alberta’s oil markets beyond the United States by pipeline to the west coast is, as the NEB noted, for the benefit of all Canadians.

Getting Alberta’s oil to west coast terminals should be seen as not just a provincial or regional project but a nation-building project. Canadians have an interest in seeing Trans Mountain proceed. In the event it does not, however, the government should not needlessly shut down the Eagle Spirit Energy Corridor, a viable alternative route on First Nations’ lands with First Nations in control. It is essential that Bill C-48 be either defeated or amended to exempt Lax Kw’alaams Nation’s territory and the development of the Grassy Point terminal.

Photo: Shutterstock, by pan demin.

Do you have something to say about the article you just read? Be part of the Policy Options discussion, and send in your own submission. Here is a link on how to do it. | Souhaitez-vous réagir à cet article ? Joignez-vous aux débats d’Options politiques et soumettez-nous votre texte en suivant ces directives.