Canadian policy makers and business leaders have a rare opportunity to resolve a critical environmental concern even as they help revive the economy. In the freight transportation sector — in the hands of North America’s dispatchers, train engineers and long-haul truckers — climate change solutions offer the chance for a win-win result.

That’s the conclusion from a new report from the Secretariat of the Commission for Environmental Cooperation (CEC), a study pointing out that virtually all of the policy and infrastructure changes that are necessary to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in the transportation sector also improve economic efficiency.

Destination Sustainability examines the opportunity to improve the environmental impact of freight transportation in Canada, the United States and Mexico, which, depending on one’s viewpoint, is either a worsening source of GHG emissions or “low-hanging fruit” — a ready opportunity to make gains in the battle against climate change.

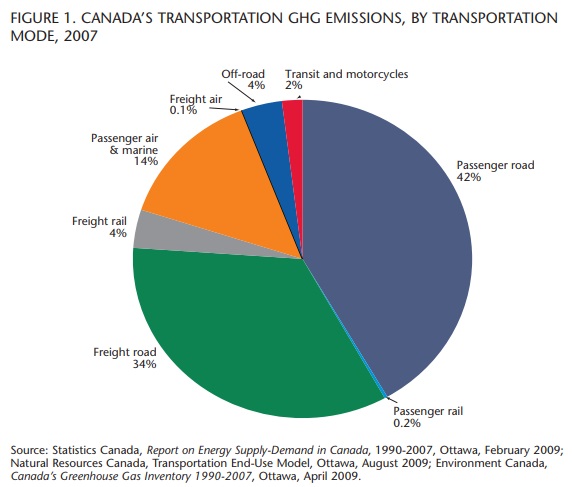

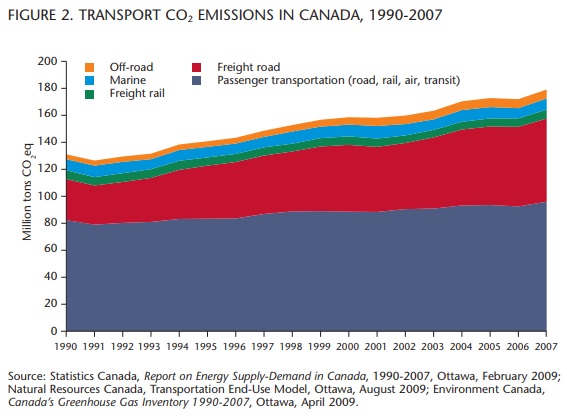

In looking at that battle from a sectoral perspective it’s apparent that transportation in general, and freight transportation in particular, must figure prominently in each country’s GHG mitigation strategies (see figure 1). In North America, transportation is second only to electricity generation as a source of CO2 emissions, and freight transportation is the fastest-rising component in that category (see figure 2).

Moreover transportation energy demand is expected to grow substantially — 90 percent between 1990 and 2030 — far outpacing growth in other sectors. At this rate, by 2050, transportation will overtake industry to become Canada’s highest energy-consuming sector. In Canada, freight transportation accounted for approximately 38 percent of the sector’s GHG emissions in 2007.

The good news is that the environmental performance of this sector is particularly amenable to improvement with the application of readily available and emerging technologies. Studies in both Canada and the US have made the case for dramatic emissions reductions — up to 50 percent — that could be achieved within five short years with the uptake of new fuel and vehicle technologies, as well as the adoption of intelligent transportation systems.

The bad news, of course, is that it’s not that simple. For the trucking mode in particular the uptake of such technologies is frustrated by low profit margins and disaggregation. As in the building sector, hundreds of thousands of owner-operators and small entities may be unable or unwilling to make the longer-term capital investment — absent unambiguous incentives and price signals — into the greenest equipment and systems.

Moreover, the promise of such potential efficiency and environmental improvements is confounded by three challenges: economic growth; everincreasing volumes of surface trade; and the growth of continental supply chains concurrent with deeper integration of the economies of Canada, the United States and Mexico.

Looking forward 20 years, the US Department of Transport (DoT) projects a 42 percent increase in vehicle miles travelled. Thanks in large part to continuing improvements in fuels and technology, it estimates emissions from personal and light-duty vehicles will drop by 12 percent over this period. It is particularly vexing to note, however, that freight-related emissions are forecast to increase by 20 percent over this same period, despite similar expected improvements in fuels and technologies. More freight trucks, moving more goods to more customers — despite efficiency improvements — will increase, not decrease, freight-related GHG emissions.

Such an increase may seem acceptable in comparison to the growth expected in the NAFTA region over the same period — with a population swelling to 540 million and the North American economy growing between 70 and 130 percent. But to avoid disastrous climate change, scientists agree that our emissions should be going down, not up.

According to DoT’s Bureau of Transportation Statistics, trade between the United States, Canada and Mexico in March 2011 reached $80.8 billion — the highest monthly trade figure since the collection of data on surface transportation between NAFTA partners began in 1994.

At this rate, by 2050, transportation will overtake industry to become Canada’s highest energy-consuming sector. In Canada, freight transportation accounted for approximately 38 percent of the sector’s GHG emissions in 2007.

As over 85 percent of US trade by value with Canada and Mexico is moved overland, the increase has translated into better returns for NAFTA road freight operators. This increased trade puts increased pressure on Canada’s and North America’s freight transport infrastructure.

Canada’s international trade flow is concentrated geographically, and as a result the top six border crossings — Windsor, Fort Erie and Sarnia in Ontario, Lacolle in Quebec, Emerson in Manitoba, and Pacific Highway in British Columbia — together handled around 73 percent of total truck traffic by value. Bottlenecks and the sheer volume of traffic at these border crossings pose challenges in logistics and infrastructural development and concerns related to increases in emissions associated with transportation.

Essentially, Canadian freight transportation doesn’t operate in a vacuum, and there are increasing calls to develop an integrated North American freight transportation system. A voiding disastrous freight-related transportation GHG increases over the near term requires not only continued progress in developing fuel economy, technologies and alternative fuels, but also the vision and will to create an integrated, intelligent freight transportation system that encompasses the entire NAFTA region. A large number of studies and reports and a wide range of transportation stakeholders have identified challenges confronting freight transportation in North America.

Many have called for national and North American approaches to sustainable transportation.

The US National Surface Transportation Policy and Revenue Study Commission, for example, stated that the transportation challenges facing the United States have reached crisis proportions. Others, including the Canadian federal government, have at times recognized the importance of an international perspective.

The Canadian Chamber of Commerce advocates treating the Canada-US border as part of the freight supply chain and passenger travel system. The Chamber claims that if the border works well, it will allow the countries’ economies to grow and will support the 7 million jobs in the United States and 3 million in Canada that rely on a close partnership. Likewise, the Chamber believes that enhanced linkages between the various passenger modes of transportation will encourage public use of transit, further reduce congestion on highways and help to reduce the carbon footprint of the transportation network.

Key issues identified in our report include deferred maintenance of basic infrastructure, crippling traffic congestion and the near total dependence of the freight transportation sector on fossil fuels. More specifically, we identify 11 areas in which progress, on a North American scale, is required:

- pricing carbon

- reducing border delays and enhancing security

- integrating transportation and land-use planning

- shifting to more efficient transportation modes

- shifting to lower-carbon fuels

- increasing the efficiency of transportation technologies

- funding transportation infrastructure and pricing its use

- greening supply chains and encouraging sustainable production

- acquiring data and developing performance metrics

- reducing demand for inefficient freight transportation

- Improving freight transportation governance and stakeholder networking

Our first and most fundamental recommendation is that Canada, the United States and Mexico work more closely together to foster an integrated freight transportation system. To help address challenges posed by climate change we recommend putting an effective price on carbon, sending a clear market signal to invest in efficiency and in low-carbon alternatives. We also urge governments to reinvest in the transportation system itself — in the road, rail and waterway infrastructure that is, in some cases, congested, deteriorating and/or lacking the modern technologies that could improve efficiency.

There are efforts already under way such as a US-Canada partnership between the Environmental Protection Agency’s SmartWays Program and Canada’s FleetSmart. The partnership will share information about products and services that reduce transportation-related emissions such as new technologies, management and logistic practices, as well as eco-driver training.

Modal shifting — of long-distance freight from road to rail or to waterways — has also been promoted as a solution to reducing GHG emissions. In today’s market, intermodality, facilitated by the ubiquitous 20-foot container, is a well established economic choice expressed by many carriers as they respond to myriad and widespread customers in the most costeffective manner.

While CO2 reduction gains can be made by shifting freight transportation from high-energy/high-CO2-emitting modes to more-efficient modes, this has proven to be difficult to accomplish in practice. To date, GHG emissions reductions due to modal shifts have had mixed results compared to other policies, notably those related to fuel efficiency and carbon intensity. More fundamental is the chronic failure, in any of our three countries, of transportation prices to internalize the full cost of environmental and other externalities. When freight transportation prices do not reflect such costs, not only may one mode have a distorted cost advantage over another, but all of us pay for the environmental, public health, congestion and economic consequences.

An early and perhaps insufficiently lauded environmental accomplishment by US President Barack Obama was the 2010 announcement that the United States would establish GHG emissions standards for commercial medium-and-heavy vehicles, beginning with model year 2016. The announcement noted that large tractor-trailers emit half of all GHG emissions from the commercial trucking sector. More recently, Canada has also announced that it will adopt the US standards, with appropriate adjustments for Canadian conditions.

Unfortunately, as referenced briefly above, as important as these new standards promise to be, they are insufficient to solve the problem of increasing freight emissions. Our three countries require a portfolio of coordinated policies, informed by a continental perspective. The CEC Secretariat’s report points to a unique opportunity for the three countries to better align their transportation policies and practices in order to meet the challenges associated with increased trade associated with a common North American supply chain.

Efficiency — including transportation efficiency — is one of the elements that have made North America the global economic superpower. The policies, regulations and incentives necessary to accomplish sustainable freight transportation can restore our competitive edge and be a trigger in reviving North American prosperity.

The CEC secretariat, based in Montreal, undertook an independent study on freight transportation in North America in order to make recommendations to the CEC’s Council of Federal Environment Ministers from Canada, the United States and Mexico. More information about the secretariat’s report is available at https://www.cec.org/freight.

Photo: Shutterstock