Proposed changes to the Citizenship Act under Bill C-6 went to the Senate this week. Whether senators will introduce amendments that either facilitate or restrict citizenship remains to be seen.

One aspect overlooked by MPs in their consideration of the Bill was the impact of the Conservative government’s amendments to the Citizenship Act (C-24) and other related measures. Those changes made citizenship “harder to get and easier to lose,” and it’s unclear the degree to which C-6 provisions would counter the related decline in naturalization.

It should be noted that many of the Conservative changes were needed to address significant weaknesses in the integrity of the citizenship program, ranging from test administration, inconsistent language assessment, and residency requirements.

To recall the Conservative government’s main changes:

- Expansion of language assessment and knowledge testing ages from 18 to 54 to 14 to 64 along with greater integrity and more consistent implementation

- A more rigorous study guide, Discover Canada, and associated test, with a higher pass mark required (75 compared with 60 percent)

- More aggressive anti-fraud and misrepresentation measures

- More than quintupling the cost of citizenship from $100 to $530, as well as maintaining the “right of citizenship” fee at $100 and third-party language assessment costs for some applicants of about $200

- An increase in residency requirements from three out of four years to four out of six years, where residency is defined as physical presence, and the addition of an “intent to reside” provision requiring applicants confirm their intent to reside in Canada

- Removal of the partial credit for pre-permanent-resident time toward citizenship for international students and others

- Administrative and integrity measures to streamline processing and improve integrity;

- Ministerial discretion in revocation in cases of misrepresentation, without recourse to the courts

- Citizenship revocation in cases of terror or treason

Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada’s (IRCC) operational data allow us to analyze the impact of these changes, and Statistics Canada data highlight longer-term trends.

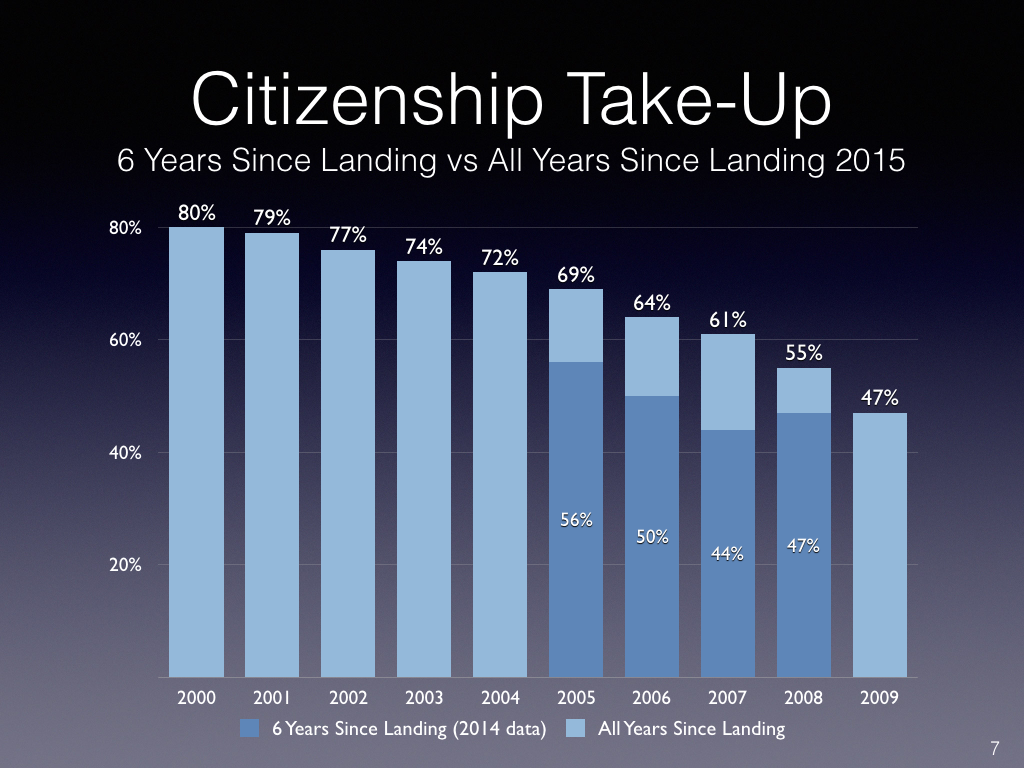

Figure 1 shows an overall decline in the naturalization rate, a trend that started before the Conservative changes. While the naturalization rate for all immigrants is 85.6 percent, this is heavily influenced by older cohorts of immigrants who naturalized to a greater extent than recent cohorts.

According to Statistics Canada, 93.3 percent of the foreign-born who immigrated prior to 1971 had become Canadian citizens, compared with 77.2 percent of immigrants who came between 2001 and 2005, and 36.7 percent of newly eligible immigrants who arrived between 2006 and 2007 and had become Canadian citizens by 2011.

Likely reasons for the decline in the naturalization rate include the fact that some immigrants leave Canada because of a lack of economic opportunities (an estimated one-third of male immigrants leave Canada within 20 years), greater overall mobility among immigrants and citizens and consequently a less identity-based view of citizenship.

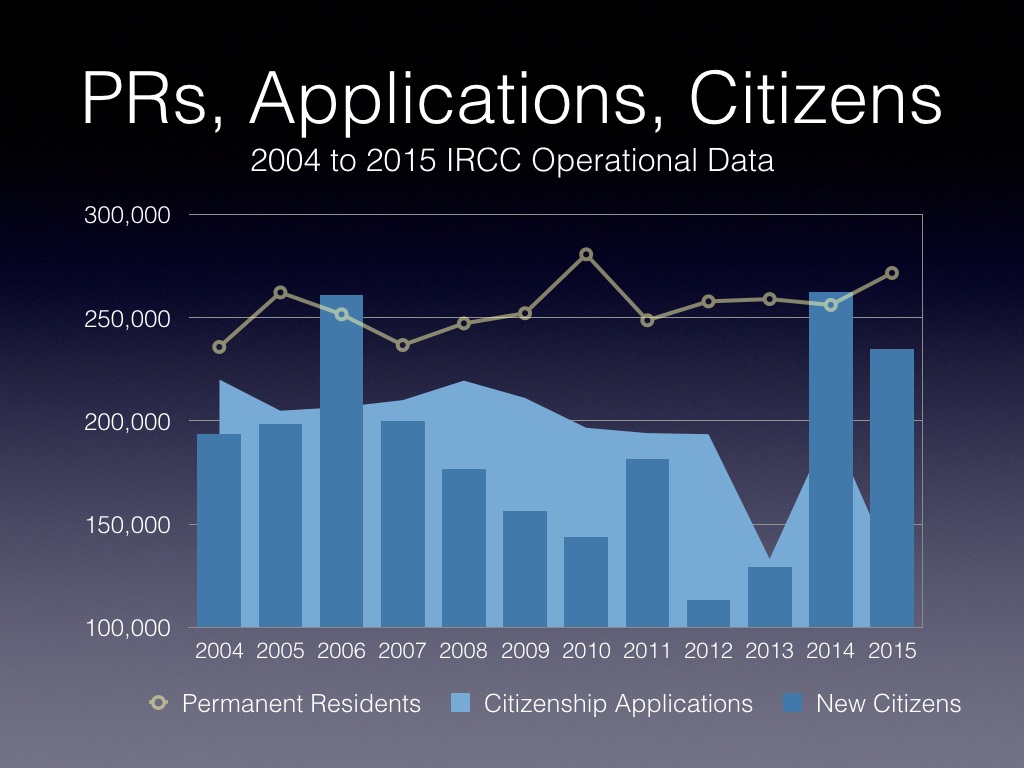

Figure 2 contrasts the stability of permanent resident (immigrant) intake compared with the rapid fluctuations in the number of new citizens, and a general trend of declining citizenship applications. This reflects both historic operational and funding challenges. The Conservative government injected $44 million to address the backlog and allow for record numbers of new citizens in 2014 and 2015 (the previous Liberal government injected $66 million to address a similar backlog in 2005).

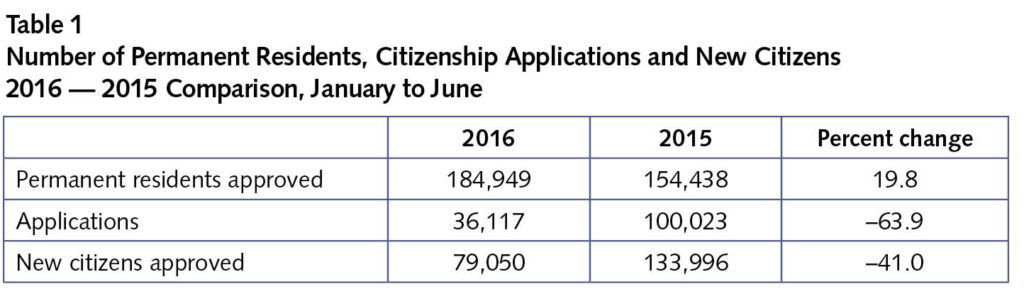

However, the overall trend of declining applications appears to be accelerating. Table 1 compares the first half of 2016 with the first half of 2015 with respect to permanent residents, citizenship applications and new citizens. The 2016 rise in the number of permanent residents reflects the government’s new plan to receive 300,000 immigrants this year.

The drop in the number of new citizens is not surprising, given that the backlog has been addressed (from a high of 323,000 in 2012 to 59,000 on 30 June 2016), meaning there are fewer applications to process. However, the dramatic, and I would argue, alarming drop (64 percent) in the number of people applying to become citizens belies departmental assertions in the Canada Gazette 2014 notifications that the number of applications was “not anticipated to fall following an increase in the fees.”

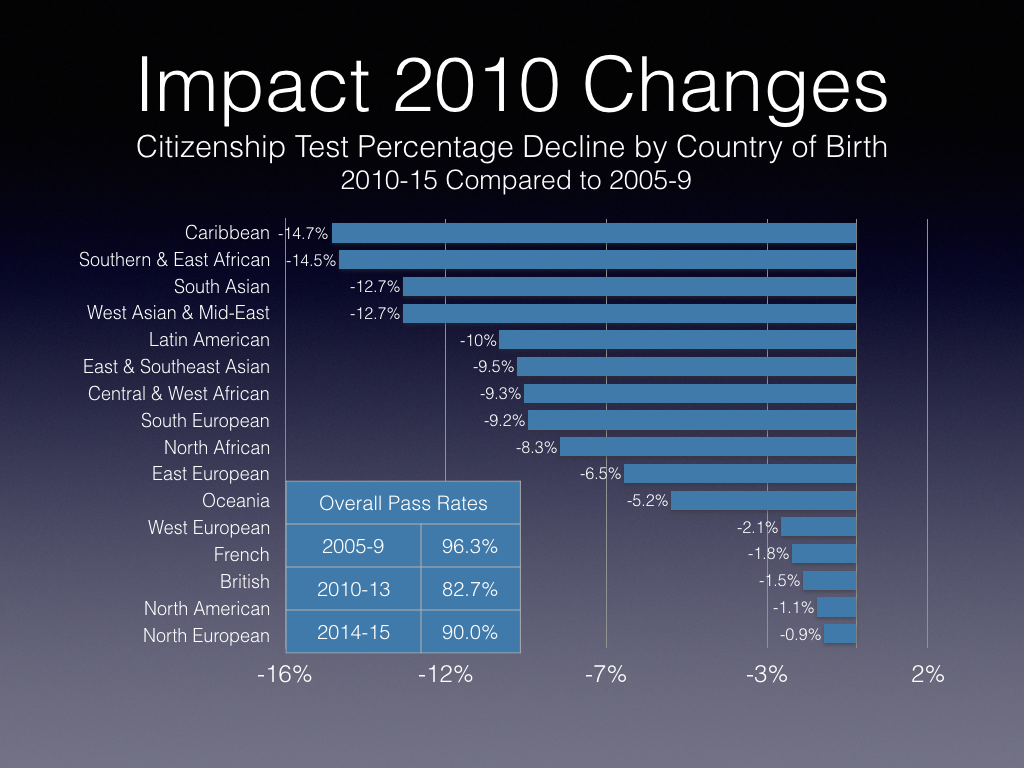

Changes to the citizenship test in 2010 had a major impact on visible minority immigrants. The pass rate of 96 percent before the new test was introduced fell dramatically between 2010 and 2013, before wording changes were made that made questions more understandable. The pass rate increased somewhat.

Figure 3 contrasts the effect of the changes on different ethnic groups from 2005 to 2009 to 2010 to 2015, highlighting the impact on groups, generally visible minority, where language fluency and education are often weaker. Although I have not examined the data with respect to language, it is likely that the same pattern would be found.

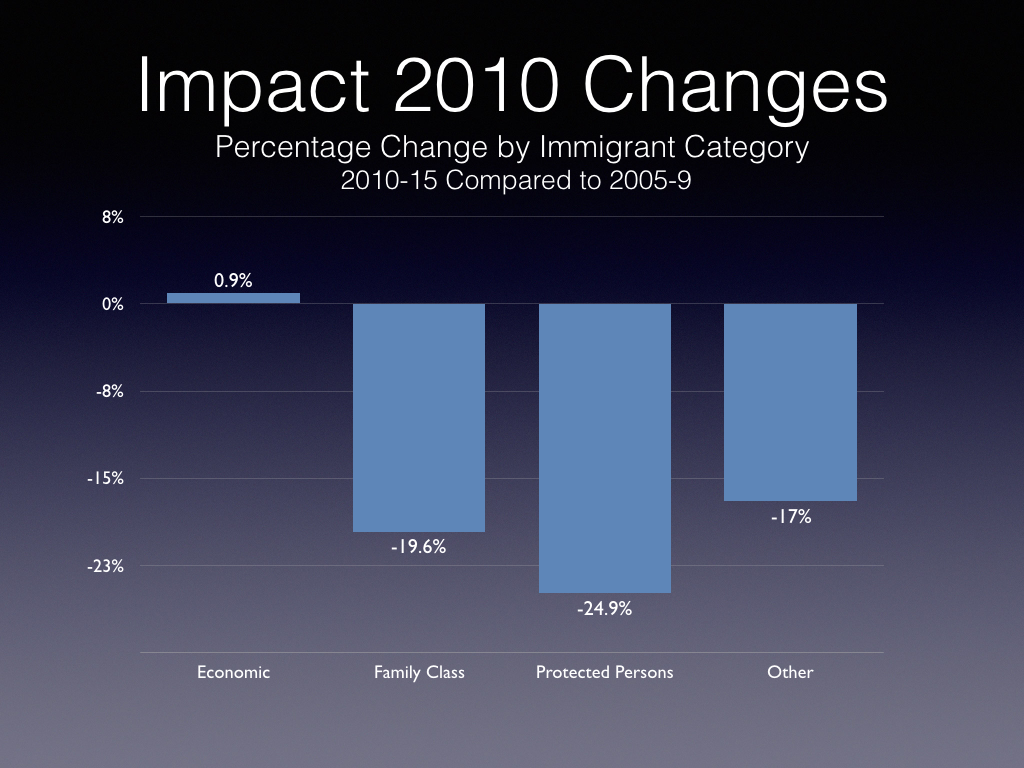

Figure 4 demonstrates the same phenomenon but from the perspective of immigrant categories, again comparing the annual average of new citizens from the six-year period 2010-15 to the annual average of the five-year period 2005-09 before these changes. The tighter language and knowledge requirements largely contributed to sharp decline in the family class and protected persons class. The main subgroups affected in the family class were parents and grandparents (there was a 20 percent decline, compared with a 2.5 percent increase in the number of spouses). The main subgroups affected in the protected persons class were government-assisted and landed-in-Canada refugees (13.3 percent and 17.5 percent decline, respectively, compared with a 12 percent increase for privately sponsored refugees).

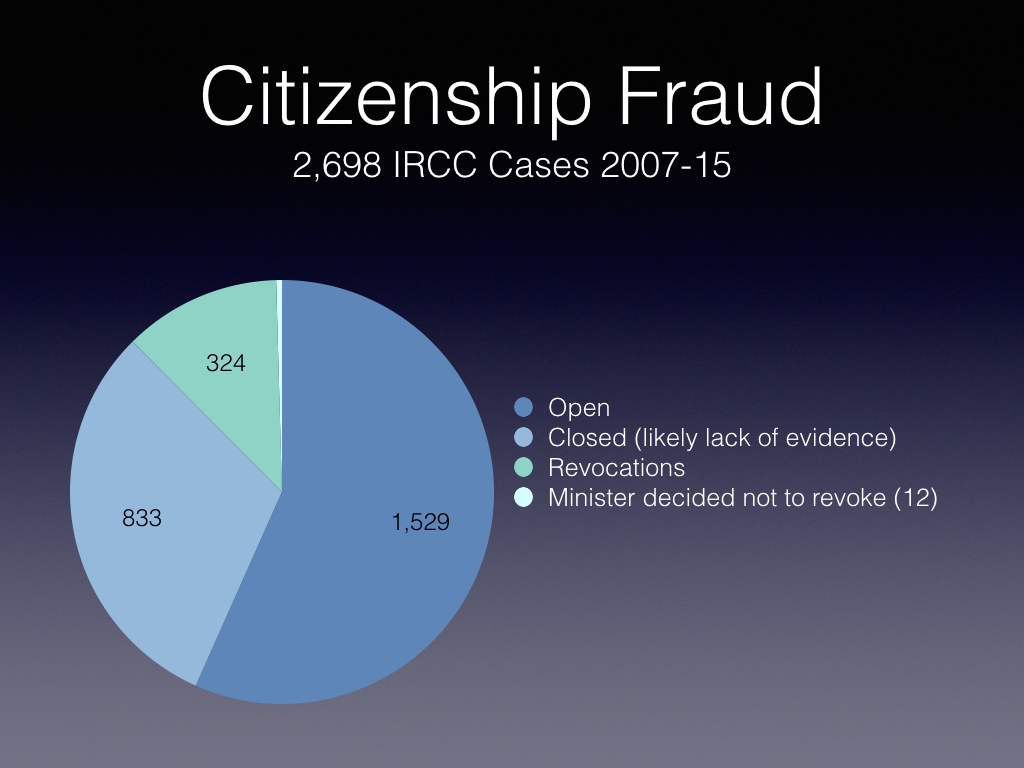

It is unclear the extent to which the much vaunted anti-fraud efforts impacted citizenship uptake. In figure 5, the 2,700 fraud cases investigated by IRCC from 2007-15 are broken down by number of open investigations, closed investigations (likely due to lack of evidence), actual revocations, and the few cases where the minister decided against revocation. In addition, during this period 143 cases that were investigated by the RCMP resulted in applicants withdrawing or abandoning their applications.

In addition to the overall value of maintaining the confidence of Canadians in the citizenship program, the anti-fraud efforts likely deterred misrepresentation among newer applicants. However, in relation to the 1.6 million new citizens during this period, the actual number of cases, whether open, closed, or resulting in revocation or withdrawal, is tiny: 0.18 percent.

All this demonstrates that the Conservative government essentially succeeded in their policy objective of making “citizenship harder to get and easier to lose” through these operational and administrative measures.

Will Bill C-6 and related measures reverse this overall trend? Given the relatively modest and limited changes, it’s unlikely. In many ways, the degree to which the Liberal government maintained and strengthened the needed integrity provisions of the Conservative government’s C-24 is one of the great untold stories about C-6.

The repeal of citizenship revocation for terror or treason will have minimal or no impact on naturalization rates, given that revocation has limited to no demonstrated deterrence effect, and given the extremely small numbers of those engaged in such activity, whether here in Canada or abroad (between 100 and 200, according to CSIS).

The reduction in residence requirements from four out of six years to three out of five years may produce a transition “bump,” as those who applied under the old requirements are combined with those who apply under the new, shorter period, but it is unlikely to have a longer-term impact on citizenship take-up, given the fact the Liberals are maintaining the physical presence requirement.

The raising of the age range for knowledge testing and language assessment from 14 to 64 to 18 to 54 will have some impact for the older group. The department’s operational data for the years 2009 to 2013 (the years prior to this change coming into effect) shows an average of slightly over 10,000 of all those tested (5.5 percent) were aged 14 to 17 and just over 11,000 (5.9 percent) were between 55 and 64. Given that 14-17-year-olds would have spent a minimum of four or five years in the Canadian school system, requiring language assessment was unnecessary, and removing this requirement should not make a difference in overall naturalization for this group.

The main impact of this change will be waiving the requirements on 55-64-year-olds, likely leading to an increase in citizenship take-up for people in this age group with weaker language competency and low comfort in being tested. Citizenship acquisition by parents and grandparents was affected by the more difficult test and language assessment, so removal of this requirement will result in more new citizens.

The restoration of the partial credit for time spent in Canada prior to becoming a permanent resident, particularly relevant for international students in Canada, may make a slight difference to the naturalization rate. The main barrier to naturalization for international students is the fact that the Express Entry program currently awards half of all points to those with job offers or to newcomers nominated by the provinces, which places many students at a relative disadvantage.

The other announced change, along with C-6, was the Minister’s intent to rewrite the citizenship study guide, Discover Canada, so it is aligned more to the Liberal government’s priorities and its diversity and inclusion agenda. Changes in its content are not likely to affect pass rates. However, the redrafting of the guide and the test questions using plain language and bringing it closer to the Canadian Language Benchmark Level 4 (the passing requirement), should improve the pass rates for those who have struggled with the higher level of language currently used.

Should the government be concerned about the decline in Canada’s naturalization rate, the likely biggest impact would come from reducing citizenship fees from the current $530 to a level closer to our main comparator country, Australia, which charges AUS$325, or C$315. The government would also need to look at lowering the cost of language assessment (about $200 for those without Canadian education or government-funded language training).

According to documents received under the Access to Information Act, the department successfully sought an exemption to the User Fees Act to allow for large increase in Budget 2013. Costing of the citizenship program carried out in 2011-12 justified this increase, but the accompanying analysis largely dismissed any impact on the number of applications and consequently new citizens. We now have numbers that show that this did affect significantly on the number of applications.

The User Fees Act exemption should be repealed to ensure that any future changes follow a full public consultation and regulatory process, rather than merely being announced after the fact in the Canada Gazette.

Fundamentally, citizenship is about finding the appropriate balance between encouraging or facilitating citizenship and ensuring a meaningful connection to a country, in the context of an increasingly global and mobile people.

The Conservative government made a number of needed operational and policy changes to improve the integrity of becoming a Canadian, resulting in a decline in the naturalization rate. The Liberal government has reversed a number of these changes but appropriately maintained and enhanced these integrity measures.

While Canada’s naturalization rate will remain one of the highest in the world, the changes in Bill C-6 are unlikely to reverse significantly the overall trend of a declining naturalization rate.

While theoretically, Canada’s ongoing policy is to encourage all to become citizens through a meaningful connection to Canada, the overall rate of 85.6 percent reflects the combined naturalization rates of earlier waves of immigrants and a declining rate among more recent immigrants. The official target, according to IRCC’s performance report, is 75 percent for all immigrants, a largely meaningless number as it does not specify a timeframe and does not distinguish between previous and more recent immigrant cohorts.

Recent data suggests that some 75 to 80 percent of eligible immigrants who apply for citizenship do so within six years from their year of landing. A meaningful target would measure how many apply within that period of time, or perhaps slightly longer. Based upon current trends and today’s ever increasing global mobility, I would suggest for discussion purposes a target of between 65 and 70 percent citizenship uptake within 8 years.

Having a meaningful target rate for recent immigrants would help us determine whether Canada has the right balance between facilitation and meaningfulness in its citizenship program.

Photo: Monticello / Shutterstock.com

Do you have something to say about the article you just read? Be part of the Policy Options discussion, and send in your own submission. Here is a link on how to do it. | Souhaitez-vous réagir à cet article ? Joignez-vous aux débats d’Options politiques et soumettez-nous votre texte en suivant ces directives.