I first met Jane Philpott on a cold winter morning in 2015, not long after she was sworn into her first cabinet post as minister of health. I was working with three Saskatchewan First Nations to address the opioid crisis, and it was their hope that I could communicate the reality on the ground to the newly minted minister. Sitting around the table were Philpott, her political staff and senior bureaucrats. Knowing her background as a physician, I framed our issues around a lack of quality improvement, patient safety and patient-centred care. I was blunt in targeting specific issues within the First Nations and Inuit Health Branch of Health Canada. Several participants bristled at my comments. Philpott sat engaged and thoughtful, asking for clarification and occasionally signalling for her department to quietly listen.

Looking back, I understand why my words were hurtful to many around that table that day. In speaking my truth and the truth of these three Saskatchewan First Nations, harm was identified, and trauma was uncovered. As a provider, I understand that harm isn’t always intentional. Despite the best efforts of persons within government, they were failing at improving certain health outcomes. It hurts to hear that. It’s worse to acknowledge that often it’s true.

I was taught by an Elder early in my medical training that all people are ready to share their trauma, but not everyone is ready to hear it. For that reason, the truth gets suppressed and change does not occur. Philpott, who resigned cabinet on March 4, was broadly effective in her posts due to a broad set of hard and soft skills, but she was specifically effective at reconciliation because she was ready to hear other people’s trauma and not dismiss it. This is what is meant by having truth before reconciliation.

The trauma in Indigenous communities runs deep. Philpott was witness to the suicide contagions and mental health crises that run rampant across Northern Ontario, Manitoba and Saskatchewan. She bore witness to the devastating impacts of opioid abuse. She heard countless experiences of racism, health inequity and lack of health access. Later, as minister of Indigenous services, she unpacked yet more trauma of communities lacking clean water, housing and many other social determinants of health. Through it all she listened to people’s truths. She was accepting and nonjudgmental.

“When I consider the living conditions and social opportunities (or lack thereof) experienced by many First Nations, Inuit and Metis peoples, I am ashamed. I acknowledge the tremendous amount of preventable suffering, injustice and loss of life in Indigenous communities. But the future offers the opportunity and obligation to do better, to do right,” Philpott said.

Following our first meeting in 2015, I imagine, her department had vigorous discussion about my concerns. In the same way any health provider would defend themselves against allegations of patient harm, I am sure there was strong rebuttal. These were also truths, just as valid to hear.

There is a common misconception that reconciliation is one-sided. One side changes while the opposing side declares victory. This runs parallel to the polarization we see in our political systems and in the advocacy work we deploy to influence those systems.

True reconciliation isn’t about winning. It’s about understanding the fuller picture. It’s acknowledging each other’s truths and trauma, moving toward broader buy-in to what we’re actually trying to work toward and not simply what solution to apply. The effectiveness of Jane Philpott in achieving change and momentum in Indigenous health, in Indigenous services and in truly divisive issues like medical assistance in dying is a testament to her understanding that.

Since Philpott resigned from cabinet, I’ve been hearing persons of all political affiliations expressing admiration of her ability to bring people together in an environment of respect and authenticity. Like all great leaders, she’s left behind people within and without government who understand each other more as a result of her influence. For those still within cabinet, her example can be a model for their own success and effectiveness.

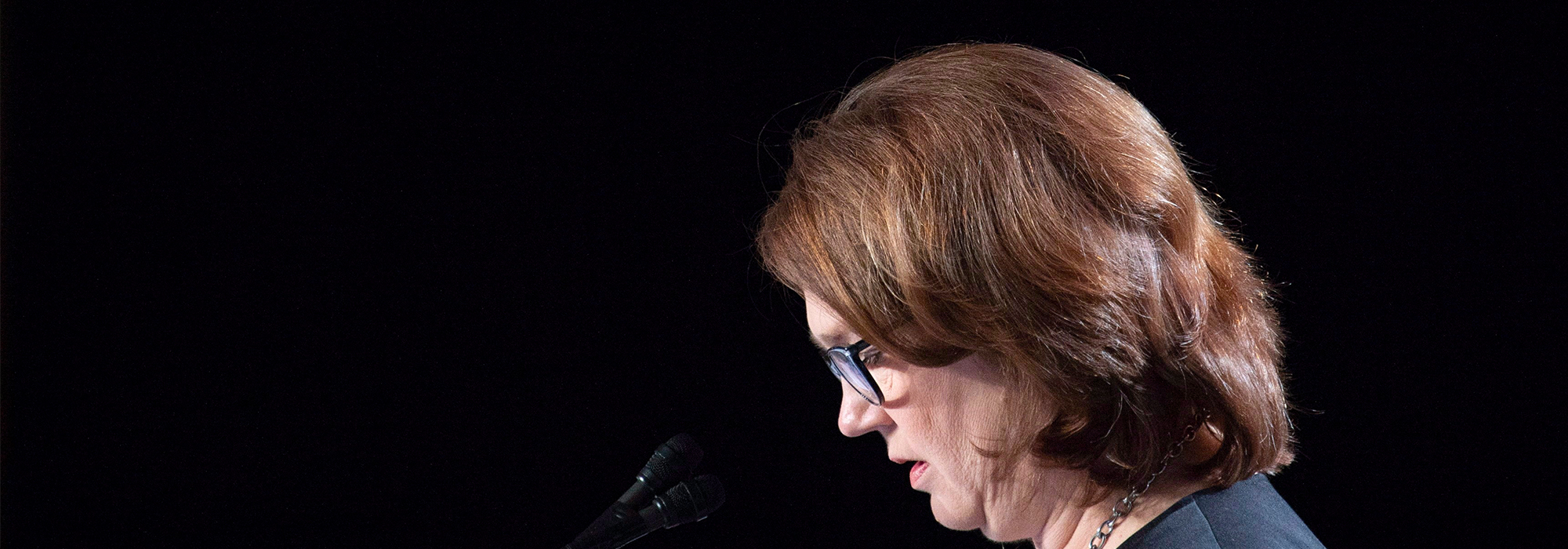

Photo: Former cabinet minister Jane Philpott speaks at the Assembly of First Nations Special Chiefs meeting in Ottawa on December 5, 2018. THE CANADIAN PRESS/Adrian Wyld

Do you have something to say about the article you just read? Be part of the Policy Options discussion, and send in your own submission. Here is a link on how to do it. | Souhaitez-vous réagir à cet article ? Joignez-vous aux débats d’Options politiques et soumettez-nous votre texte en suivant ces directives.