The following is an abridged version of the foreword to former Prime Minister Jean Chrétien’s latest book, My Stories, My Times (Random House Canada).

Politicians are best known for the things we did – or didn’t do – in office, but we have after-lives too which, among other advantages, allow the opportunity to recall, and sometimes reflect upon, things we saw and heard and felt during and after our privileged days in public office. By definition, such observations are bound to be personal, and reflect a point of view, but they can also provide invaluable context to decisions and events which others can know only at a distance. All of the dry and distant facts of history have a story, often a human story, which can be as important and informative as the event itself. Canada is fortunate that Jean Chrétien, at 84, and 55 years after his first election to the House of Commons, is publishing some of his reflections on people and events which shaped our history.

By a tradition as old as parliamentary democracy, the distance between the government and the opposition benches in Canada’s House of Commons is “two swords and one inch apart.” That is to symbolize and encourage debate that is vigorous and adversarial but not fatal – to the participants, or to the country. For more than two decades, Jean Chrétien and I sat “two sword lengths” across from one another in Canada’s Parliament.

On some issues, we had deep disagreements – probably the most important concerned certain provisions of the Constitution Act of 1982 which, as Minister of Justice, he introduced while I, as Leader of the Opposition, forced a very long parliamentary debate, winning time for televised public hearings, then a successful reference to the Supreme Court, and resulting ultimately in amendments which improved the proposed changes to Canada’s constitution. In the end, we both voted for what was called “patriation,” and for the amended Charter of Rights and Freedoms – but the two of us still disagree on the larger implications for Canadian unity and integrity of the way our constitution was changed during that critical period.

Jean Chrétien and I were each shaped by one other unique opportunity. Each of us was elected to lead our national political party, in a time when national parties reached habitually beyond their base and sought to embrace and understand the whole country, all its people, all its parts. We are both the product of an era when contact with voters was direct, face-to-face, often on contentious ground – and those actual human exchanges could temper the influence of advisors or pollsters, or sophisticated interest groups, or ideologues.

Those reality checks seem more elusive today, and the distance greater between citizens and politicians, in an era when leaders’ interactions with voters are more often electronic than personal, or by way of rallies where citizens are screened before entry. I say that not as elegy, but as explanation of the vital direct access which leaders of our earlier time were privileged to have with the lives and hopes and fears of fellow Canadians.

One of the unexpected privileges of being a party leader then was the frankness with which individual citizens would tell you their story. They may never vote for you – but they know that, sometime, you might make decisions which will affect their lives – so they want you to understand their problems and their hopes. And if your pores are open, you learn a lot in those encounters.

As time went on, Jean and I both came to understand that – just as in Canada there can be a rare frankness from citizen to leader – so, in this complex international climate, there is often a comparable openness between leaders of different countries. There are so few people with whom a president or prime minister can be frank that they sometimes confide in visiting peers, when the chemistry is right. The “little guy from Shawinigan” is pretty good at human chemistry, and his reflections on international conversations add extra dimensions to our understanding of international events.

Most Canadians are still framed by where we come from and, in many cases – Shawinigan for example, or High River – our “home town” is only a tiny part of the country, or the world, or the era in which we have to function. That poses a special challenge for political leaders, because our profession requires knitting different communities together, rather than focussing more narrowly.

Thus, two questions arise. First, how do leaders learn about our remarkably diverse country, and complicated world? As much as possible, by immersion in it, by reaching out, by being open-minded, especially when that’s hard. We all fall short; but we learn, as we grow.

So the second question is: what can former leaders teach?

The best historians and social scientists gather a rich and deep and wide array of “evidence” that is considered objective. But necessarily, their invaluable assessments are most often from the outside looking in. The dimension which former leaders can offer is reflection and perspective – and often simply stories – from the inside looking back.

I cannot vouch for the accuracy of all of the reflections in this collection. As a partisan, reading an opposing partisan, I would naturally dispute some of them. But my purpose is neither fact-checking nor peer review. I’m interested in having Canada’s human stories known.

Mr. Chretien’s… reflections on significant times and events… take us beyond what we know. They are also very human –and…..often, the opposite of the careful scripting which caricatures politics and government today.

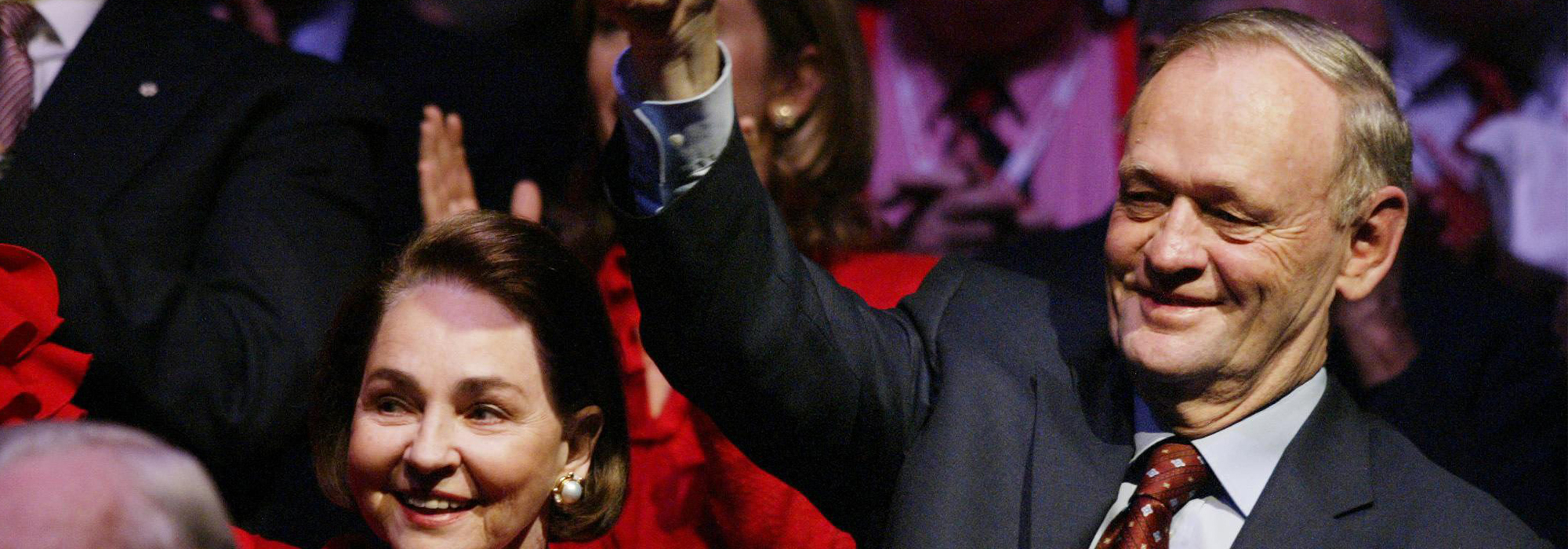

Photo: Former prime minister Jean Chrétien as his wife Aline give the thumbs-up to performer Paul Anka during a tribute at the Liberal Convention in Toronto, on Nov. 13, 2003.

Do you have something to say about the article you just read? Be part of the Policy Options discussion, and send in your own submission. Here is a link on how to do it. | Souhaitez-vous réagir à cet article ? Joignez-vous aux débats d’Options politiques et soumettez-nous votre texte en suivant ces directives.