Every revolution grows old—and so, too, do the revolutionaries. Fidel Castro’s hair is grey, he has reportedly cut down on cigars, and his speeches now last only a couple of hours (rather than all day and half the night). Meanwhile, his government has allowed foreign investors and private firms back onto the island. Cuba is still a renegade nation: After all, we didn’t invite them to the Quebec City summit because they aren’t “democratic” (somehow the US-installed governments of Haiti, Columbia, and Panama made the guest list), and the island still apparently poses enough of a strategic threat to the world’s only superpower to justify its continuing economic and military isolation. But time somehow has a way of moderating the fire in the belly that motivates younger partisans to do wild and crazy things. Cuba’s revolution today definitely exhibits a lighter, gentler shade of pink.

The same thing can happen to revolutionaries of the right, as well as those of the left. In Canada, for example, it seemed not so long ago that our economic and political culture was on the verge of a far-reaching transformation of the conservative variety. The deficit was being slain. Social programs were slashed across the board—and more importantly, the conventional wisdom that resulting popular outrage would spell political disaster for the budget-cutters was being turned on its head. Free trade was exerting its powerful, continentalist influence on the national psyche.

And these victories only whet the appetite of the neoconservative commandantes—the revolutionaries of “common sense,” in Mike Harris’s lingo. Their young bucks were suddenly in ascendance: folks like David Frum, Andrew Coyne, and Ezra Levant, bursting onto the national stage, making powerful and confident arguments, turning heads. “Conservative is cool,” argued some trend-spotters. (I never thought that any of those guys had enough fashion sense to be cool, but that’s just my opinion.) Conrad Black’s National Post provided a quickly influential national media voice for this brash, self-assured constituency.

In electoral terms, the neo-conservatives were banging on the doors of the palace; in some jurisdictions (most notably Ontario in 1995) they were gaining entrance. Alberta’s Tories, meanwhile, managed the transition to neoconservatism while staying comfortably atop the seat of power. (That is how change occurs in a one-party state.) The Reform Party rose to become a national threat—west of the Ottawa river, anyway. Most insidiously, many neo-conservative policies were enacted by governing parties which weren’t supposed to be doing that kind of thing. Even Liberals jumped on the bandwagon. Along several axes, the economic policies of the Chrétien regime have clearly been the most right-wing of any federal government of the post-war era: It engineered by far the deepest peacetime reductions in government spending in Canadian history, is now enacting the largest tax cut in Canadian history, and has implemented numerous other initiatives that turned long-time conservatives red with envy. After all, in Brian Mulroney’s judgement the greatest fault of the current federal government is that it stole all his ideas and didn’t give him credit. The Liberals poised to take power in British Columbia don’t look very liberal, either, by our traditional understanding of that label.

But for all the apparent momentum of the political right, and for all of the significant (and in most cases socially painful) changes it has wrought, there’s a more recent sense of humility, confusion, and even resignation among the architects of this true-blue crusade. The failure of the Canadian Alliance to win seats in Ontario, or even to unite federal right-wing votes, is the clearest setback. But the problems go deeper than that. Canadians from coast to coast are clamoring for more public spending: on schools, on roads, on parks, above all on health care—even on boring things like infrastructure. The political payoff from tax cuts is not yet apparent; many Canadians don’t even notice that their taxes have been cut (which suggests that they probably paid a lot less in taxes in the first place than the minions of tax rage claimed they did). Unions persist in causing trouble. Rank-and-file Canadians do not seem to have woken up and smelled the neoconservative coffee: They are still demanding more from life than the free market alone can provide them with.

All of this is taking its toll on the revolutionaries. Stockwell Day has his well-publicized troubles, few of which would have lingered had he been more successful in delivering the electoral goods. The vim and vigour of senior cabinet ministers in Ontario has been waning visibly for years—some (like Ernie Eves) lured away by the bigger salaries offered in the private sector, others by distractions of the extra-marital variety. Conrad Black’s National Post can’t turn a profit—which is, after all, the ultimate test of legitimacy for any free-marketeer—and he has sold out to a Liberal. I can already picture them all sitting around the cigar lounge at the National Club, wistfully recalling the days when it looked they were riding a wave of history—a well-heeled counterpoint to a reunion of aging guerillas around a jungle campfire, wondering what happened to the world revolution they were fomenting.

In the March issue of Policy Options, editor William Watson provided a humorously bleak overview of the successes and failures of the neoconservative revolution. And he sees many more failures than successes. Watson has self-confessed libertarian tendencies, and supports many of the policy directions of the new right. But he thinks that neo-conservatism has peaked, and the best years of the revolution are already behind us. “My bet is that in 25 years,” Watson concluded, “neo-conservatism will be regarded as, alas, an historical curiosity.”

On one hand, I am tempted to treat Watson’s self-deprecating judgement with the same skepticism wise heads reserve for a pool shark. Someone who comes into a pool hall making a big deal out of how they’re really not a very good player, emphasizing their failures instead of their successes, is probably someone who’s deliberately hiding their true skill until the big money has been placed on the table. Listening to a prominent neo-conservative complain about how neo-conservatism really hasn’t accomplished very much, how there’s much more work to be done, sounds like the same kind of set-up. Everyone knows that politics is about moving the goalposts, about shifting popular expectations regarding what is possible and what is reasonable. If you actually stood up and claimed victory (or even acknowledged you had the upper hand), you would undermine your case completely for further movement toward your end of the playing field.

But on the other hand (unlike most economists I only have two), I actually think that Watson’s conclusion is justified. This raised the eyebrows of some of my left-wing friends at the University of Manitoba’s Delta Marsh retreat (where we all met last fall to analyze the rise and fall of the neo-conservative juggernaut), although it wasn’t the first time that, playing against type, Watson and I have agreed in public. Now, I don’t think that he defines neo-conservatism correctly. We also differ on the ways in which neo-conservatism has changed Canadian society, and to some extent on the time frame involved. But I agree that the neo-conservative project remains, at best, incomplete, and that the political and economic pendulum is probably already swinging back the other way.

Watson defines neo-conservatism largely as a philosophy of small government. Government should be smaller, less intrusive, and above all should collect less in taxes, according to the neo-conservative maxim. And indeed, it is the data indicating the persistence of historically high rates of aggregate taxation that are, for Watson, the most discouraging proof that neo-conservatism has failed.

I define the whole question rather differently. What if the relevant issue is not the size and power of government, but rather in which direction and in whose interests that power is wielded? Even socialists might not be pleased with a massive, well-funded, and powerful government bureaucracy—if it turned out that its power was being used for evil, instead of for goodness and light. After all, no band of socialists ever advanced the slogan: “Increase the size of government, now!” Their slogan, instead, was “Power to the people!” The left has pushed for government to do certain things (some of which, but not all, required government to be “bigger”). The new right, in response, has pressed for government to stop doing some of those things, and to start doing other things instead (some of which, but not all, are consistent with government getting “smaller”). So neo-conservatism is not, in my view, primarily an effort to downsize or disempower government. It represents an attempt, rather, to restructure and reorient government programs and regulations so as to protect and enhance the interests of a certain constituency: private businesses and investors, whose actions in mobilizing capital and hiring workers are essential for the success of any economy rooted in private ownership and private markets.

Some forms of powerful government regulation are highly desired and supported by business. Consider, for example, one of the most powerful levers of government policy: the actions of the central bank (ultimately an indirect arm of government, no matter how much it pretends to be independent) in setting interest rates so as to control the pace of growth in the entire economy. It’s hard to imagine a more intrusive and effective tool of government intervention. This public agency, under the tight stewardship of a tiny group of technocrats, makes decisions that affect the bottom-line costs and profits of virtually every company in the country. Millions of people can be thrown out of work if this agency deems that the labour market is “too hot.” Little wonder that Alan Greenspan is universally considered to be the most economically powerful person on earth—and private business, for the most part, would like to keep it that way (and not solely because of Greenspan’s fondness for the works of Ayn Rand). Private businesses (especially financial businesses) generally like the fact that the entire course of the economy is in the hands of a small, unelected public agency (even though they often second-guess the decisions of that small clique). They think this is the best way to control inflation and hence guarantee the continuing worth of accumulated stocks of financial wealth.

The successful introduction of anti-inflationary monetary policy was a key priority of neo-conservatism, and nothing about it implies “weak” government. When macroeconomic policy shifted in a neo-conservative direction, this lever of government if anything became stronger, and it certainly began to be used towards a different goal—namely, the protection of financial assets, regardless of the cost imposed on those who do not own wealth. There are other times, too, when neo-conservatives like “strong” government: when governments are tracking down and convicting farmers who violate the patent rights of biochemical firms, for example, or investing heavily in workforce training (so that employers can reduce their on-the-job training expenses), to cite but two examples.

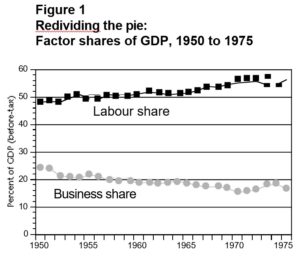

I also date the advent of neo-conservatism differently. Neo-conservatism arrived in Canada long before any of the individuals or organizations we currently identify as neo-conservative gained our attention. Our policies began shifting in a neo-conservative direction in the early 1980s. This shift represented an historic aboutface, relative to the direction of policy over the previous decades—when government became a lot bigger, yes, but more importantly became more willing to interfere with the actions of private businesses, and even (in a few cases) to take over those businesses entirely. Taxes approximately doubled as a share of GDP between the end of World War II and the mid-1970s, but no tax revolt was inspired: partly because taxpayers appreciated the new public programs that those taxes were paying for (like medicare, public pensions, and a dramatic expansion of unemployment insurance in 1971), and partly because taxpayers’ disposable private income was still growing despite the tax hikes (thanks to robust growth in pre-tax incomes). Private investment during this time was strong, creating millions of new jobs, and labour conditions were further strengthened by the creation of millions of relatively well-paying public sector positions. On the strength of sustained low unemployment, growing and militant unions, and an increasingly comprehensive social infrastructure (which supplemented private incomes and hence made Canadians less dependent on their employers), Canadian workers became a feisty lot: We had more strikes than any other industrialized country but Italy, and labour’s share of the economic pie grew steadily. Business profits were squeezed on all sides—by workers, by taxes, by regulatory constraints on their activities, by the growth of the non-profit sphere of the economy, and by increasing competition from other companies. Total business profits fell from about 25 per cent of GDP after World War II to an average of just over 15 per cent during the 1970s (see Figure 1). Not surprisingly, business investment also fell, and the Golden Age expansion began to sputter.

This set of developments was hardly unique to Canada; similar trends were occurring in most other industrial economies, where business was also experiencing a gradual but ultimately dangerous challenge to its dominant role in economic growth, and indeed to its role in society in general. By the mid-1970s, businesses and the individuals who own businesses decided they didn’t like the way this ship was heading. Profits on real production were eroding. High inflation produced negative real returns on most financial assets. Employment relationships were troubled, reflecting the demands of a confident, empowered workforce (whether unionized or not) for better treatment on the job. Perhaps the most dangerous element in this volatile mix was an increasingly antibusiness political and cultural tone in society—visible most obviously in the rebelliousness of youth, but in a myriad of other ways, too.

After an unstable period of grappling with this state of near-crisis, and groping for an internally consistent policy response, neo-conservatism (or neo-liberalism, as the phenomenon is termed in most countries) was born. Its general goal was to protect and restore the former dominance of private businesses and investors in both the economy and in broader society. Numerous specific policy thrusts, all of which were applied in Canada beginning in the early 1980s, were consistent with this general goal:

- Controlling inflation and restoring financial profitability. The 1970s were a bitter decade indeed for financial investors. The consistently tough financial policies which have been imposed since can even be thought of as the “revenge of the rentiers.” Investors will forever remember the negative returns they experienced in the 1970s, due both to rising inflation and to the eroding real profitability of corporations. Their lasting bitterness explains their still-intense fear of any uptick in inflation. (The fact that financial losses in the stock market meltdown of the last 12 months probably rival those incurred in the inflationary 1970s is cold comfort. Since the bursting of the high-tech bubble was largely a self-inflicted wound, financiers can’t complain too much.)

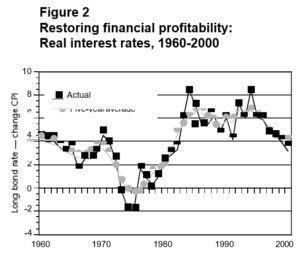

The arrival of tight-money policies in Canada in the early 1980s was like a cannon shot signaling the arrival of a new era. Real interest rates rose dramatically—and stayed high, contrary to those who argued that high interest rates were a short-term pain required to capture the long-term gain of lower inflation. As indicated in Figure 2, real returns on long bonds have averaged close to six per cent (above inflation) since 1981. There is some cyclical variation, of course, but financial investors today can count on real returns significantly higher than during the first three decades of postwar expansion. Wrestling inflation to the ground has only accentuated the after-inflation profits that can be earned by sitting atop large piles of financial wealth.

This permanent shift in monetary policy has carried numerous consequences. Labour markets are maintained with a deliberate cushion of slackness, to reduce wage pressure. The opportunity cost of investing in a real business (and hence the hurdle rate of return for that business) has grown; this both reduces the quantity of real investment spending and enhances the return on those investments which do occur. With less money pumping into real productive businesses, increasing amounts of creative energy are expended on finding new and ever more-clever ways to profit from purely financial placements. This explains the hyperactive growth of our modern financial industry—with questionable implications for real growth and productivity.

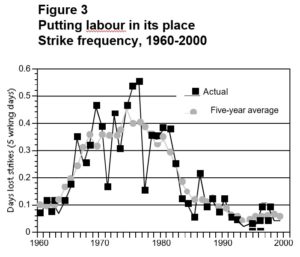

- Restoring discipline to labour markets. Tight-money policies went a long way to reimposing a little bit of fear in the minds of Canadian workers. Full employment was explicitly toppled from the podium of macroeconomic policy-making, replaced by low inflation and financial stability. This thrust was reinforced by structural efforts to deregulate labour markets, and recreate a social and economic environment in which if you don’t work, you don’t eat. Income security measures for working-age Canadians were cut back dramatically. This generated the twin benefits of producing a more fearful and hence compliant workforce, while at the same time saving the government oodles of money. Real-wage growth, which for much of the Golden Age expansion exceeded the growth of real productivity (hence causing a redistribution of income toward labour), has since 1981 largely lagged behind real productivity growth (resulting in a redistribution in the other direction). In the 1970s Canadian workers were likely to show up on the job and fight for their rights; by the 1990s they were bowing their heads in thanks each morning that they still had a job. No indicator better captures this sea change in labour relations than the decline in strike frequency (Figure 3). Average days lost to work stoppages in the 1990s were 85 per cent lower than in the 1970s.

It is argued that this deregulation and redisciplining of labour markets actually allows the labour market to come closer to a full employment equilibrium—as evidenced, supposedly, by low unemployment in the “flexible” US labour market. There is a grain of truth to this claim, though not for the reasons often suggested. It has not been convincingly shown that “flexible” labour markets are actually more efficient at allocating and reallocating labour between different industries or occupations, and otherwise facilitating efficient “adjustment to change.” There is some evidence, however, that central banks may be more easy-going on the interest-rate lever when labour markets are disciplined and workers insecure. A central bank may demand unemployment of 10 per cent to restrain wage pressures when workers are unionized, minimum wages are high, and social supports are generous. It may be happy with five per cent, however, when unions are on the defensive, the social safety net is shredded, and workers are perpetually vulnerable (and hence more likely to be happy with what they’ve got). In this case, a deregulated labour market may indeed allow lower unemployment—not through some magical free market mechanism, but (ironically) because the most powerful regulatory agency in the entire economy changes its behaviour accordingly. (Alan Greenspan gave famous testimony to this effect to a US Senate committee in 1997, arguing that chronic worker insecurity despite falling unemployment allowed him to keep interest rates low; this has since become known as Greenspan’s “fear factor” testimony.)

- Trimming and refocusing government programs. There is clearly something to the conventional wisdom that neo-conservatism is aimed at downsizing government programs. Some forms of government activity obviously are non grata in a world in which private investors and private firms are given the job of organizing production, hiring the people to do it—and making money in the process. Relatively rare government experiments with the direct public ownership of productive firms were obviously a first target for the neo-conservatives, and this was reflected in the wave of privatization that began in the 1980s. Services which used to be provided by public agencies as a matter of course were also farmed out; the attempted privatization of Canada’s neglected water and sewage infrastructure may be the next battleground in this grand trend. Government social programs were also targeted: especially those which offered any degree of economic security to those Canadians who “should be out working for a living.” This explains why anti-poverty programs focused on children and seniors are seen as widely legitimate, but any measures to reduce poverty in the working-age population are fiercely contested. Indeed, in a business-led economic and social regime, it is helpful to have a certain amount of poverty around—and the more visible, the better. It’s a potent reminder to the working population of exactly why they should get up every Monday morning, commute to work, and obey their bosses’ every command. No surprise, then, that employment insurance, welfare, disability pensions, and any other social benefit which can possibly be claimed by a working age person have been the first targets for the budget-cutters. The goal was not so much to tackle the deficit; if that was the motive, then these cutbacks could be undone in this era of sizeable budget surpluses, with lots of money to spare. No, the main goal was to reduce the limited extent to which a person could get by in life without offering their services for sale on the private labour market.

So to some extent, government has indeed become smaller during the neo-conservative era. Non-interest program spending by all levels of government, for example, fell to 33 per cent of GDP in 2000, a decline of almost one-quarter since peaking at 42 per cent only seven years earlier. Some of this decline, of course, was cyclical in nature: Strong economic growth simultaneously shrinks the numerator of that ratio (by reducing the need for unemployment benefits and some other programs) and enhances the denominator (by growing the size of the economy). But most of this contraction in government program spending is structural in nature. Program spending is now smaller as a share of GDP than at any time since the early 1970s. Most ominously, it is still falling despite the attainment of balanced budgets in 1997, and the emergence since then of large fiscal surpluses. This suggests that something other than the elimination of deficits was a primary motive behind the spending cuts.

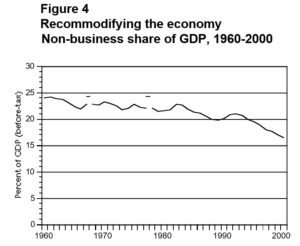

By other measures, the retrenchment and refocusing of government activity began much earlier than 1993. Consider Figure 4, for example, which illustrates the relative size of the non-business sector of Canada’s economy (including government agencies, public programs such as schools and hospitals, and other non-profit undertakings). It indicates a secular downward trend in the relative importance of the public sector since the early 1980s, which has shrunk by almost one-third (as a share of GDP) since 1981. Another view on the same trend can be attained by measuring public consumption (the value of all direct non-cash public programs and government activity) as a share of private (personal) consumption spending; this ratio also peaked in the early 1980s at just under 50 per cent (indicating that Canadians then consumed almost 50 cents in public services for each dollar of private personal spending). This ratio has since fallen by one-quarter, to about 35 per cent. By all of these measures, government programs have been significantly downsized, and in the course of this downsizing special attention has been paid to the reduction of activities (including income security measures for the working-age population) which posed the maximum difficulty for private firms and investors.

Taxes are still high by historical standards, to be sure. To some extent, this reflects the lingering effects of the attack on the deficit. If the neo-conservatives have their way, taxes will now fall: Taxpayers, especially the high-income taxpayers who foot most of the tax bill under Canada’s highly progressive income tax system, will receive the long-awaited payback for the austerity of the last decade. In the neo-conservative view, this will be additionally beneficial in reinforcing the influence of market incentives in shaping economic behaviour.

Taxes may not fall as much as we think, however, for several reasons—not the least of which is growing public pressure to repair some of the damage to public programs experienced in the budget-cutting 1990s. And it is possible to imagine a neo-conservative society in which taxes remain relatively high. If the money is used by governments to finance activities which are less harmful to business, and which may even help business (protecting property, for example, including increasingly abstract forms of intellectual property, or training workers with just the right skills, or subsidizing corporate research and development), then taxes and neo-conservatism are not at all inconsistent.

Has it all worked? Has the neo-conservative U-turn, implemented to reverse business setbacks which culminated in the 1970s, succeeded in recreating an environment more hospitable to private investment and business-led growth? There have obviously been some important changes in the Canadian economy, our society, and even our culture. The dominance of private business as the crucial leading force in economic and social development has been restored, and is even—in some circles—celebrated. Business profits rebounded later in the 1990s, as our economic recovery finally gathered steam. Ironically, however, profits have only recovered to about the same level they were at in the late 1970s, when the profit squeeze and resulting economic and financial instability motivated a radical change in policy direction. Because of their contractionary impact on overall demand conditions and hence on the ability of companies to sell their goods and services, most neoconservative measures initially hit business profits hard. In this regard, neo-conservative medicine is tough to swallow, and slow to work.

Once macroeconomic conditions can be stabilized, however, then business can hope to take full advantage of a playing field that has been tilted in its favour. In the US the combination of pro-business structural features with an expansionary macroeconomic stance allowed for very strong profitability through most of the 1990s. In Canada it’s been more difficult for the neo-conservative regime to find and maintain that “sweet spot”: an economy that’s hot enough for companies to generate strong profits, but not so hot that workers start to get uppity. Even in 2000, the strongest year of the current upswing, business profits in Canada were unremarkable by any historical or international measure. If corporate Canada can’t make money in this environment, when can it? The situation became more worrisome still as, by the end of the decade, the until-then enviable US model started to reveal its vulnerability to problems and contradictions, both extrinsic and inherent—ranging from the self-destructive bubble-chasing of financial artists, to rising private debt loads, to the inevitable energy and environmental crises that will result from its resource-gobbling modus operandi.

On the cultural front, Canadian businesses still fight a losing battle for the hearts and minds of the population. Canadian executives complain regularly that our national culture is too antibusiness. After years of threatening to leave the country because of Canada’s high taxes, Nortel Networks CEO John Roth recently threatened to leave purely because Canadians were being too critical of him and his company (in the wake of a $300 billion meltdown in Nortel shares that was probably exacerbated by poor management strategy). Many Canadians have probably resigned themselves to the seemingly inevitable reality that business will continue to call most of the shots in our economic and social lives. That doesn’t mean that we like it, though. Canadians seem to resolutely resist the worship of wealth and power that is common south of the border, and this sparks continuing complaints from the possessors of these idols.

Meanwhile, Canada’s governments are leaner and meaner, but still obviously significant players in the economy. The economic and social interventions of the state have been reoriented so that they are more compatible with business needs, even if that means they are less compatible with social goals (like the reduction of poverty). Inequality in Canadian society is growing markedly. In terms of pre-tax market incomes, inequality has grown dramatically during this (broadly defined) neo-conservative era, reflecting the deregulation of labour markets and other factors. Until recently, this growing inequality was offset by the tax-and-transfer activities of Canadian governments, which powerfully reverse much of the polarization produced by the market. Since 1996, however, inequality is growing significantly even measured in terms of disposable incomes—for the first time in a quarter-century.

The increasingly visible inequality and poverty faced by many Canadians, despite years of economic expansion, is sparking powerful calls for new anti-poverty measures and other forms of redistribution. And governments face continuing demands to restore funds to other public programs they have cut—not to mention provide additional funds for brand new public initiatives (ranging from early childhood education to pharmacare to home care). Meanwhile, despite the overall deregulation of labour markets, Canadian workers continue to demonstrate their willingness to promote their own self-interests, whether they are unionized or not—as evidenced by the recent wave of painful strikes in various public sector agencies across the country. On the whole, then, while the neo-conservative revolution has certainly won some important battles, its victory is hardly complete. Canadians have been told for the better part of two decades now that good times will roll once again, if only we can get our economic fundamentals in order. Twenty years of hand-wringing and belt-tightening later, the private sector of our economy has yet to experience a fundamental rebound in vitality. The willingness of Canadians to continue making sacrifices and concessions in the interests of restoring a regime of business-led growth may be reaching a limit.

Ontario is the best place to examine and understand the stalling of the neo-conservative project in Canada. The Harris government was probably the second-purest neo-conservative regime in the country, next to Ralph Klein’s. Besides, Alberta has always been a special case: a tolerance for one-party rule, more pickup trucks per capita than anywhere else in the country, a long-standing receptiveness to economic and cultural individualism. (As a native Albertan, I am allowed to say things like this in print.) Ten billion dollars a year in oil and gas royalties doesn’t hurt, either. In Ontario, however, the common sense revolution runs smack into central Canadian sensibilities: the noblesse oblige of Upper Canada’s old money, the ethnic and economic diversity of the population, and a tradition of public provision and social security that is still relatively strong despite years of spending cuts and bad-mouthing. (I learned this after living in Nova Scotia for two years, where taxes are far higher than Ontario, but the quality of public services much lower.)

On first blush, it seems that the Common Sense Revolution was successful. In its first term, the Harris government socked it to welfare recipients: The reduction in real welfare benefits now totals 30 per cent since 1995, and the belt gets tighter with each uptick in consumer prices. It repeatedly took on the big, bad unions—not winning every battle, but certainly putting labour on the defensive. It declared Ontario “open for business” once again (implying that the province had somehow become an intolerable place for its rich and powerful denizens during a decade of middle-of-the-road Liberal and NDP rule). It abolished employment equity and pay equity laws, a favourite whipping boy of the long-suffering white male. And the revolution’s shining achievement, of course, was the 30 per cent cut in provincial personal income tax rates (measured until recently as a share of federal income taxes)—a promise that seemed so audacious when Harris first made it that his opponents unwisely wrote him off as an extremist. Despite years of protests and turmoil, Harris was re-elected in 1999, with special thanks to his strong base of support in rural and suburban regions.

Not long into the second term, however, it became increasingly clear that many common-sense revolutionaries were losing their religion. A sneaking feeling of unease has infiltrated the government, a widespread sense of a ship adrift. The big battles—against welfare abusers, union bosses, and taxes—have been fought and won. And yet Ontario still, in most respects, looks amazingly like it did before Harris rode to the rescue. What comes next? Or is that all there is to this “revolution”? The government suffered serious political damage from the Walkerton water tragedy, supplemented by subsequent fall-out from widespread concern over the decline of other public services (from emergency rooms to public schools to overcrowded superhighways). Addressing these concerns has led the government to the unthinkable: handing out dollops of new cash—not enough, mind you, but a step in the right direction nonetheless—for health care, public transit, and municipal services. Despite the damage control, the Tories linger around 30 per cent in the opinion polls, 20 points back of the Liberals. They’re not as unpopular yet as the BC NDP, to be sure—but the sense that these people represent an up-and-coming power has definitely dissipated.

When all else fails, the government knows it can always pick another fight with organized labour. Its pollsters still advise, for example, that sparking a showdown with the provincial teachers’ unions is a sure vote-winner. But Ontarians may be tiring of this war of attrition between the provincial government and the public service workforce, especially since every outbreak leads to more inconvenience and disruption in the delivery of public services that are already iffy at best. And the Harris regime’s big new initiatives in union-busting are laughable for their timid symbolism: the forced disclosure of the salaries of union officials—which is in fact a healthy measure that will push those unions which don’t yet do this to become more accountable to their members—and requiring unionized employers to post step-by-step instructions on how to decertify the union (as if anti-union employers never provided this information to dissident union members as a matter of course). If this is the stuff of revolution, then methinks the revolution has run its course.

Even in fiscal affairs, always regarded as the government’s strongest suit, chinks are appearing in the common-sensers’ armour. The Ontario government was one of the last in the country to balance its budget in the 1990s, despite a windfall of revenues generated by the export-led boom in the manufacturing sector. This is because they were more committed to tax cuts than to balancing the budget—despite all that common-sense talk about “living within our means.” With fears growing of a US-led economic slowdown, it has become suddenly apparent that the provincial economy still stands on the fiscal precipice. Like the Peterson Liberals before it, who also balanced their budget only at the peak of a long economic expansion, the Harris Tories may soon discover that recessions do nasty things to the government’s bottom line.

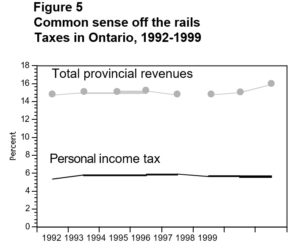

Worst of all, even though tax cuts were the highest (and most expensive) fiscal priority of the common-sense revolutionaries, it’s not at all clear that they have generated a lasting political payoff. Many people in Ontario are still not entirely convinced that they even had a tax cut—and that skepticism is in fact justified by some surprising economic evidence. In 2000, for example, Ontario personal income taxes collected an estimated 5.5 per cent of pre-tax personal income in the province—down only fractionally from the 5.8 per cent collected in 1995, and higher than the 5.2 per cent which Bob Rae’s communist revolutionaries expropriated from taxpayers in 1992 (see Figure 5). Counting federal income taxes and payroll taxes (like CPP and EI premiums), total average effective personal taxes have actually grown in Ontario during Harris’s time in the saddle. (By the way, this makes it a little hard to credit tax cuts for the boom in provincial consumer spending during the late 1990s, but that’s another story). If we count all provincial revenues, the Harris government took in more money in fiscal 1999, measured as a share of provincial GDP, than any other government in Ontario’s history—almost 16 per cent of GDP, up noticeably compared to when they took office in 1995. And this doesn’t count the higher stealth taxes that Ontarians now pay in various forms, from user fees at their children’s schools to coming hikes in municipal taxes (the fall-out from Harris’s municipal downloading).

How do we explain the incredible disappearance of Mike Harris’s incredible tax cut? Statutory marginal tax rates were certainly cut by 30 per cent, yet the provincial government collects tax at as high an effective rate as was ever the case. Several factors lie behind the apparent anomaly. The government’s highly progressive “fair share health levy,” introduced simultaneously with its first tax cuts in 1996, has become a silent money machine—collecting billions of dollars in taxes each year from high-income Ontarians. Income growth (some of it real, some of it inflation induced) has pushed many Ontarians into higher tax brackets, even as rates within each of those brackets were cut. Until last year, Ontario’s tax code piggy-backed on the federal rules, so Ontario reaped the benefit of federal tax increases. Finally, booming corporate and sales tax revenues have more than offset the modest loss in income resulting from personal income tax cuts. (It should be noted that this surprising outcome is not a so-called “Laffer curve” result, in which lower tax rates stimulate more economic activity and hence total tax revenues are unchanged; in Ontario’s case, it seems that average effective tax rates never actually fall.)

The upshot is that Ontario tax revenues have remained healthy despite the anti-tax bias of the government—which somehow nevertheless remains its defining feature. With the exception of some high-end taxpayers whose tax savings are measured in six figures or more, most Ontarians have a hard time finding their tax cuts on their pay stub. Of course, when all is said and done, provincial income taxes only collected a nickel out of each income dollar in the first place. You can play around with that nickel a lot; it is the trend in the overall dollar that will still carry the dominant influence on the economic consciousness of taxpayers. And while Ontarians may experience a vague disappointment that tax cuts haven’t really changed their lives, there’s far more pressure now to increase public spending in Ontario than there is to cut taxes. Schools need playgrounds, gridlock needs relief, water systems need replacing, teachers and nurses need a raise on pain of a continuing haemorrhage of good staff, and—above all—health costs grow every year.

This is all bad news for the common-sense revolutionaries, struggling to recapture some of that first-term spit and vinegar, and facing the departure or disinterest of several of their senior commanders. Never mind the stubborn public perception of a drifting second-term ship. It turns out that even the rugged first-term accomplishments of this rebel army were not nearly what they seemed to be. Ontario’s experience is a warning for anyone else hoping that tax cuts, even big ones, will cure all that ails us. And it is perhaps a signal that the neo-conservative revolution really is starting to run out of gas.

And so we reach a typically muddled Canadian conclusion. The neo-conservative remaking of Canada was loudly announced amidst the deficit-slaying, free-trading, and tax-cutting of the 1990s. This right-wing onslaught had deeper roots, however, and it did not reflect, first and foremost, a hatred of government, nor even a hatred of taxes. It was motivated more fundamentally by a perceived challenge to the economic, political, and even cultural pre-eminence of private business—a challenge which peaked, in retrospect, in the 1970s. To be sure, by many indicators Canada since then has become a leaner, meaner, more market-sensitive and business-dominated place than at any time in recent decades. Inequality is growing markedly—even in after-tax, after-transfer terms. An atmosphere of discipline, fear, and hunger has been reintroduced to the labour market. Government has been trimmed and refocused: It still collects a lot of tax money, yes, but it uses that money in ways that are generally less threatening to, and in many ways actually supportive of, the actions and interests of private businesses. To some extent, business has responded accordingly: Profits are up (though not dramatically so), business investment is up (though it remains unstable), and productivity is improving (albeit sluggishly). Even by the Fraser Institute’s cockeyed formulae, Canada looks pretty good: We scored seventh in the entire world in their 2000 ranking of countries according to the amount of freedom and protection offered to private firms and investors. (The Fraser Institute calls this their “index of economic freedom.” But since its component variables all reflect the relative ease with which individuals can earn and keep profits through private business activity, I prefer to think of it as an “index of capitalist freedom.”)

And yet the neo-conservative victory remains, at most, incomplete. The institutions of the “just society,” while on the defensive, have hardly been routed. Support for the public provision of key services, like education and health care, remains bedrock-solid—so much so that even the Canadian Alliance must clothe itself in the garb of universality, no matter how awkwardly that suit fits them. Canadians are rabble-rousing in hundreds of different ways, in hundreds of little battles, for a better deal in return for the taxes they pay: demanding a new park here, a subway line there, another MRI machine in that hospital over there. The outcome of all of these small, very particular struggles will determine whether all-government program spending (as a share of GDP) continues to fall, or turns back up. Like William Watson, I see a true test of the neoconservative challenge coming as Canadians decide how to allocate the fiscal dividend that will be produced by the shrinkage of debt service charges at all levels of government. My guess— optimistic for me, pessimistic for him—is that much or even most of it will be spent on public programs, as Canadians express and ultimately enforce their preference that life should have more to offer than solely that “never-ending scrabble for free-market survival.”

Maybe it’s the socialist Prozac I take in my orange juice every morning, but I remain reasonably confident that we’ve seen the worst of the neo-conservative revolution—and survived to tell our kids about it (before we truck them off to their low-cost spaces in state-subsidized daycare centres). Mind you, I lose significant sums of money to pool sharks all the time. Honest!

Photo: Shutterstock