After a decision from the highest court in the country, we were hoping that British Columbians would be able to freely express themselves in the upcoming provincial election (scheduled for May 9), without having to worry about the risk of jail time or fines if they don’t register with the government first.

In its decision, handed down on January 26, the Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of the controversial BC law, the Election Act, in effect since 1995, that requires registration of “election advertising sponsors.” But its vague wording meant even citizens who spent little or nothing on so-called advertising feared being caught in the net: the Court clarified that the law applies only to “sponsors” of advertising, as that word is commonly understood. In other words, only individuals who either pay others for advertising services or receive advertising services from others for free are “sponsors” within the meaning of the Act.

We hoped that the confusion that had reigned during past elections was finally coming to an end, but Elections BC had a different idea.

Less than a week after the Supreme Court handed down its decision, Elections BC put out a bulletin that barely acknowledges the Court has changed the rules of the game.

Among the new requirements, it is an offence (punishable with up to a year in jail and/or a $10,000 fine) for someone to “produce and personally hand-out more than 25 copies of homemade signs or pamphlets during the campaign period.”

In the Supreme Court judgment, there is no support whatever for such a proposition, and it is unclear where Elections BC came up with this figure. In an interview, one official stated this was done “for administrative purposes.” According to Elections BC, free expression somehow turns into paid advertising when a person crosses an arbitrary threshold of 25 pamphlets.

The bulletin gets even more arbitrary: “There must be no question of who is responsible for the advertising. This means that the advertising must be hand-delivered directly to another person, not dropped in a mailbox or otherwise distributed anonymously.”

Once again, there is nothing in the Court’s judgment to support Election BC’s pronouncement that a pamphlet handed to another person is free expression, but it is somehow advertising if it is put in their mailbox. According to the Supreme Court, if a person is freely expressing themselves in a way that is not “sponsorship,” the attribution rules do not apply to them. They can choose to identify themselves or stay anonymous — that choice is an integral part of their free expression.

But wait, there’s more in the pamphlet: “Groups of individuals or organizations that conduct any sort of election advertising are advertising sponsors and must register with Elections BC before sponsoring the advertising.”

The Court was quite clear that free expression by groups and organizations is constitutionally protected expression and has to be treated in the same way as expression by individuals. The Court referred to organizations and individuals as being able to express themselves without being considered “sponsors,” as long as they were not engaging in paid advertising.

In her reasons, Chief Justice Beverley McLachlin returned to the dictionary definition of “sponsor” to provide a new and much narrower interpretation of the law than Elections BC and the BC government had been supporting.

The words of the Act, read in their grammatical and ordinary sense and harmoniously with the statutory scheme, limit the registration requirement to “sponsors” — i.e., individuals and organizations who receive advertising services from others in undertaking election advertising campaigns. The Act uses the concept of sponsorship to exempt an entire class of political expression — namely, election advertising that is not sponsored — from the registration requirement. Individuals who neither pay others to advertise nor receive advertising services without charge are not “sponsors.” They may transmit their own points of view, whether by posting a handmade sign in a window, or putting a bumper sticker on a car, or wearing a T-shirt with a message on it, without registering.

This takes the provisions back to what most people would expect they would apply to: third-party advertising, not the galaxy of types of self-expression that the Elections BC and BC government interpretation would have them cover.he Chief Justice did, however, acknowledge that “in a close case, whether a particular individual or organization is caught by the Act’s definition of ‘sponsor’ may prove difficult to determine.”)

Although the latest pronouncements from Elections BC are concerning, the BC government and Elections BC have walked back before from some of their more extreme positions since the BC Freedom of Information and Privacy Association first took them to court.

For example, before the 2009 election, Elections BC’s guide for third-party advertisers stated that electronic communications would have a cost based on various complicated criteria, including whether volunteers or contract staff produced the content. By 2013, electronic communications over the Web and social media were still considered to be advertising that required registration, but their value was set at zero.

In August 2016 (shortly before the most recent hearing in the Supreme Court), Elections BC once again reinterpreted these types of communications as not being election advertising after all. The BC government itself got rid of one of the more egregious requirements, which was that the registration form had to be notarized or commissioned by a commissioner for oaths or a lawyer.

Hopefully Elections BC will once again walk back from an unreasonable and antidemocratic position.

At a time when British Columbians are debating the wisdom of the current system for political donations, which allows parties to collect unlimited amounts from sources both inside and outside the province and the country, it seems bizarre to require that people printing and distributing 26 copies of a homemade pamphlet must register with Elections BC.

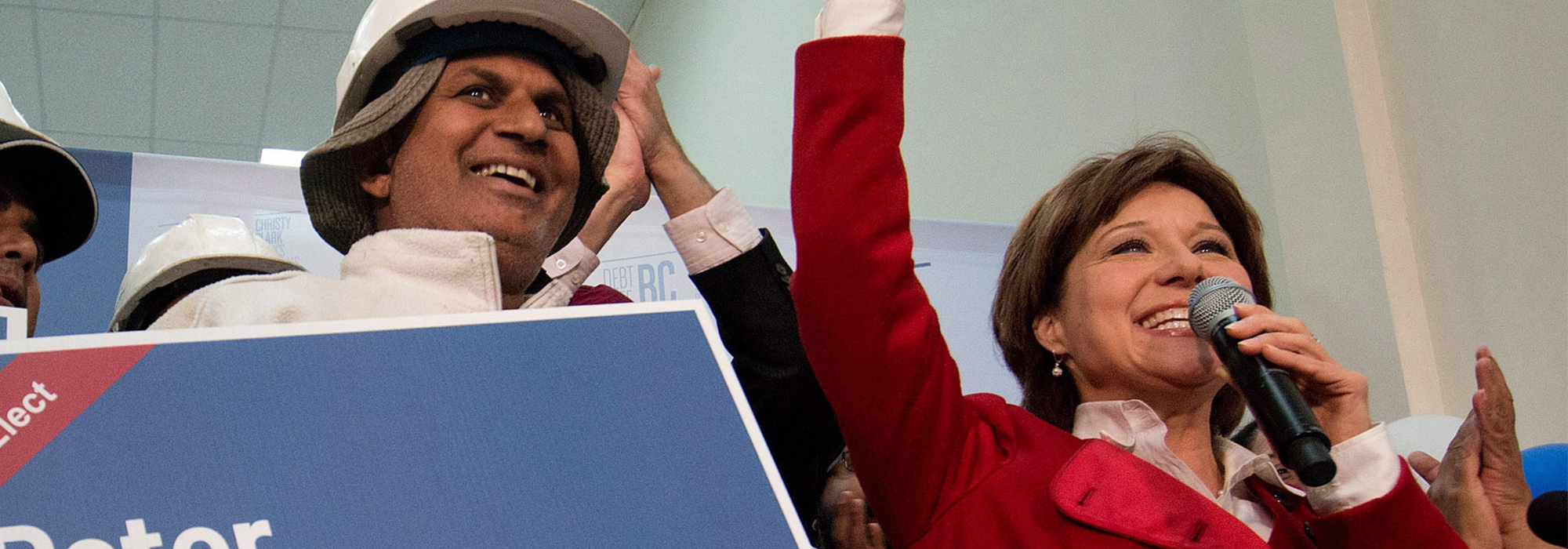

Photo: Darryl Dyck/The Canadian Press

Do you have something to say about the article you just read? Be part of the Policy Options discussion, and send in your own submission. Here is a link on how to do it. | Souhaitez-vous réagir à cet article ? Joignez-vous aux débats d’Options politiques et soumettez-nous votre texte en suivant ces directives.