Wally Nugent and Brenda Stonehouse were reviewing the ad they planned to run in the Lindsay Post for Canada Day. They were key organizers of the community’s Canada Day festivities, and the paper was where people looked to find out about local events.

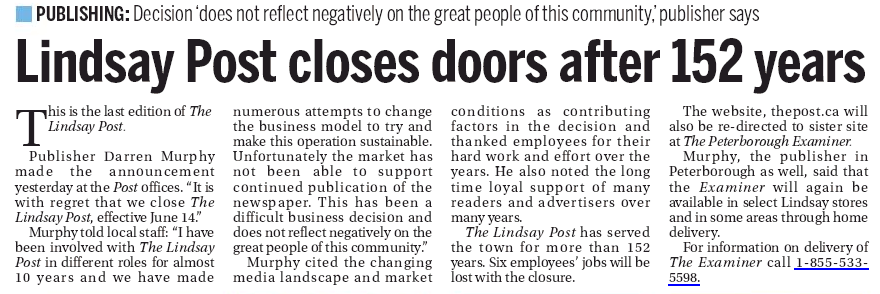

But then their phones started pinging with shocking news: The Post was closing. It would shut its doors for good, after 152 years, that afternoon.

“And we just went back to planning our ad,” says Nugent, who owns a barber shop downtown that is a hub for local gossip and political chatter. “It didn’t seem possible.”

The Lindsay Post covered news and posted details of local events for the amalgamated municipality of Kawartha Lakes in south central Ontario, a city of 73,000 composed of several rural communities. Population-wise, Kawartha Lakes is bigger than Prince George, British Columbia, Sarnia, Ontario, or any of New Brunswick’s biggest cities.

The Post’s history stretched back to 1861, six years before Confederation. That’s when the Beaverton, Ontario, Canadian Post pulled up stakes and re-established itself in Lindsay.

The Post’s story is like that of so many other community newspapers in Canada. It was originally an independently owned operation, run by the Wilson family as the Lindsay Daily Post from the 1890s to the 1980s, when it was sold to the Thomson newspaper group.

Thomson sold the Post to the Hollinger Group in 1995, which in turn sold it to the Osprey Media group in 2001. By 2007, it was sold to Quebecor, under the control of the publishing giant’s Sun Media Group, and shed the word “daily” from its masthead as it shrank to a twice-weekly publication. It closed its doors completely only six years later along with several other papers in the Sun chain.

“The writing was probably on the wall but maybe we were all in denial,” says Lisa Gervais, one of two reporters still working for the Post at the end of its life.

Sun Media Group had stopped replacing the editor when he went on vacation, leaving Gervais and her colleague to write stories, take photos and put the paper together.

“There was no, ‘We’re in trouble. What can we do to salvage this?’” said Gervais, who is now the editor of The Highlander, a weekly paper in Haliburton, about an hour north of Lindsay.

As the Ryerson University School of Journalism’s Local News Project has highlighted, when local news outlets close, the vacuum is usually not filled completely.

In Kawartha Lakes, things went from bad to worse for citizens trying to keep up with local news after the Lindsay Post closed.

Seven months later, the other Lindsay paper, Kawartha Lakes This Week, changed its publication schedule from twice to once a week. (Metroland Media, which publishes Kawartha Lakes This Week, a tabloid with a circulation of 30,000, had bought independent weeklies in the Kawartha Lakes villages of Bobcaygeon and Fenelon Falls and folded them in 2004.)

Now Kawartha Lakes This Week and the free news magazine Kawartha Promoter (delivered by mail every two weeks to about 14,000 homes) are the only print outlets based in the city.

Things aren’t much brighter on the broadcasting side. CHEX-TV in Peterborough cut its Kawartha Lakes-based reporter more than four years ago. Lindsay’s radio station, BOB-FM, which was independent until the early 2000s and is now owned by Bell Media, has one full-time and one part-time news staffer and no news director.

“We don’t pretend to be news-centric, but we do definitely want to be a source of information locally,” said BOB-FM program director Dave Illman. “The more local news sources you have, the more balanced news coverage you’re going to get.”

When it comes an election, for instance, “you might know who the candidates are, but where do you go to find out where they stand on things?” said Illman.

People living in Kawartha Lakes are among the most underserved in the country as far as political news is concerned.

A study of news coverage of the 2015 election by the Ryerson Local News Project counted only 4.7 election-related news stories per 10,000 people in the community. Nearby Peterborough, by comparison, had 20.18 stories per 10,000 people.

Since the Post’s closure, there have been provincial (June 2014), municipal (October 2014) and federal (October 2015) elections.

“The media are more stretched,” says Jamie Schmale, the local MP (Conservative) and a former news director at the Lindsay radio station. In 2015, he noticed, “they couldn’t cover as much of what we were doing. We included the local media but put more effort into social media.”

And the problem isn’t just with covering big political events like elections.

When Mike Puffer was editor of the Lindsay Post from 1988 to 1991 (he was a reporter and sports editor before that), there were enough reporters to attend meetings of school boards and council committees as well as full council meetings, where sometimes five or six reporters would show up.

Now This Week is the sole publication in Kawartha Lakes regularly covering city hall, and it goes to press on Wednesdays before the weekly council meeting has wrapped up.

“You open the paper and you see dates that have passed,” says Kawartha Lakes mayor Andy Letham. “Things are happening fast but people are not getting the news fast.”

“When you only have one reporter, who’s the voice of the checks and balances?” Gervais says. “Any two reporters in any town are going to have different reactions to what happens in a council meeting. Then at least the reader gets two perspectives.”

It’s not as if the public has lost its appetite for news in the community. This Week’s website generates a healthy number of page views per month, a large proportion of which come from readers in Kawartha Lakes, according to editor-in-chief Lois Tuffin.

Residents starved for local news are also turning to Facebook and Twitter discussions, whether through BOB-FM or This Week, or via people’s individual feeds.

That’s good and bad, says Tuffin. “I love the immediacy of it, but there’s a lack of context and a lot of half-truths.”

Gervais cites a 2016 incident in Haliburton where police responded to a call involving someone with a gun. Social media turned it into a gunman on the loose after killing three people, when it was nothing of the sort.

“Social media is a misnomer. I don’t find it particularly sociable. It’s mean and it’s nasty and it’s gossipy. There needs to be something else,” says Max Miller, publisher of the Kawartha Promoter.

The lack of reliable local coverage is a problem, Schmale says. “Everyone with an iPhone seems to think they’re a journalist now. That’s why we’re seeing the emergence of fake news. The value of having local news will never go away, but the lack of competition is not helping things in our area.”

Beyond politics and accountability, the loss of the Post and other media has affected charities, schools, churches. It’s tough to spread the word about their community initiatives says Puffer, now the communications officer for a charitable organization. “We’re all trying to fit into that very small space and it’s physically impossible.”

There’s less room for death notices, letters to the editor, events listings, photos—the things that connect people. “We used to hold press conferences for events. Now when you’re doing something they say ‘Take a picture and send it to us,”’ says Nugent, who is heavily involved in civic events, and initiatives for youth through the Optimist Club.

Is there hope for a news renaissance in Kawartha Lakes, after so many media groups failed to sustain a 152-year-old paper?

MP Jamie Schmale thinks so – pointing to the Haliburton area of his riding. With a year-round population of just 17,000, Haliburton County has the weekly Minden Times and Haliburton County Echo (owned by the same company), the Highlander, MOOSE-FM, and community radio station Canoe FM.

“I look at what’s happening in Haliburton — they have a ton of content and their advertising pages are quite full,” says Schmale.

If three papers can survive in Haliburton, surely Kawartha Lakes can support more than one, Nugent says. “In the perfect world, half a dozen local business leaders would sit down and say ‘let’s start a newspaper.’”

Miller of the Kawartha Promoter is willing to bet the appetite for local news and information — and the advertising dollars to support it — will sustain her planned expansion of the Promoter delivery area this spring. She’s realistic about the returns, but businesses need to advertise, she says. “I don’t need to make a profit, but I do need to pay the bills.”

The additional coverage will be welcome, says Nugent, as will the message it sends about Kawartha Lakes.

“To have your paper die is an indication of how your community is doing.”

This article is part of the special feature The Future of Canadian Journalism.

Photo: Nancy Payne

Do you have something to say about the article you just read? Be part of the Policy Options discussion, and send in your own submission. Here is a link on how to do it. | Souhaitez-vous réagir à cet article ? Joignez-vous aux débats d’Options politiques et soumettez-nous votre texte en suivant ces directives.