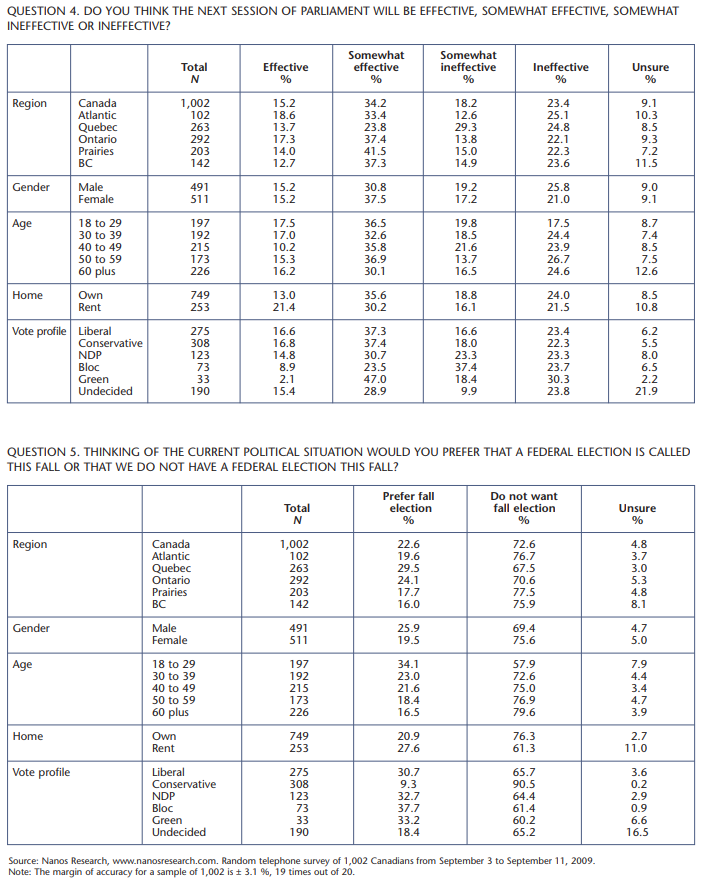

There’s no doubt about it. Canadian don’t want a fall election. And this time they really mean it. Nearly three Canadians in four, 72.6 percent, do not want a fall election, while only 22.6 percent would prefer to have one. Only 4.8 percent are unsure.

That’s a significant number, and a very hard one.

The regional breakouts are equally unequivocal. Only in Quebec does opposition to a fall election fall below 70 percent, and even there 67.5 percent of respondents, two Quebecers in three, are opposed to an early election. In Atlantic Canada, 76.7 percent of respondents oppose a fall election, while in Ontario the number is 70.6. Opposition is strongest in the Prairie provinces at 77.5 percent, closely followed by British Columbia at 75.9 percent. Essentially, three Canadians in four are flat-out opposed to a fall election.

This is just one of several clear findings in the latest Nanos Research poll for Policy Options. We interviewed 1,002 Canadians by telephone from September 3 to 11. The margin of error is 3.1 percent, 19 times out of 20. Significantly, the poll was conducted after Michael Ignatieff’s September 1 speech in Sudbury, where the Liberal leader withdrew his party’s support for the government, saying: “Mr. Harper, your time is up.”

Even Liberal voters, by a 2-1 margin, do not want an election. In the Nanos-Policy Options poll, 65.7 percent of Canadians who identified themselves as Liberal supporters said they did not want an election, whereas 90.5 percent of Conservatives said they did not want one, while 64.4 percent of NDP voters and 61.4 of Bloc Québécois voters are opposed to a fall election.

Ignatieff’s gambit immediately brought the prospect of a fall election into play, and Canadians left no doubt in our poll that they didn’t think very much of the idea. Nor is there any doubt that they would strongly approve of the decision by the Bloc Québécois and the NDP to support the government’s ways and means motion on September 18 — the defeat of which, as a money question, would have automatically triggered an October election. While the possibility of a fall election, whether by design or accident, is still out there, Canadians have made it abundantly clear to us that they don’t want one.

Still, based on past experience, the natural default of the Canadian political psyche is to resist any election.

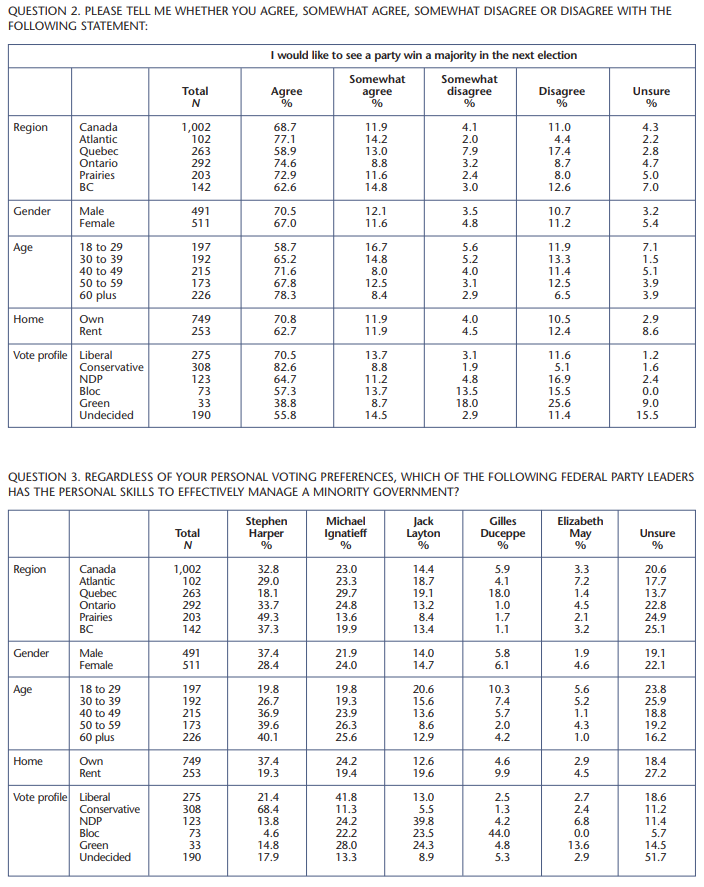

Canadians have also made it clear that while they have come to expect minority governments, they strongly prefer a majority government. Fully 68.7 percent of Canadians agree that they “would like to see a party win a majority at the next election,” while another 11.9 percent somewhat agree. In other words, 80.6 percent of Canadians want a majority government. Only 11.0 percent disagree and 4.1 percent somewhat disagree, while the remaining 4.3 percent are unsure.

Only in Quebec, whose support of the Bloc Québécois has enabled a succession of minority governments in the last three elections, is there a significant dip below the national average in terms of desiring a majority government. But even in Quebec, 58.9 percent of respondents prefer a majority government. In the Atlantic, 77.1 percent prefer majority government, while 74.6 percent of Ontarians and 72.9 percent on the Prairies would like to see a majority. In British Columbia, a three-way battleground where the NDP is a strong player, support for a majority slips to 62.6 percent.

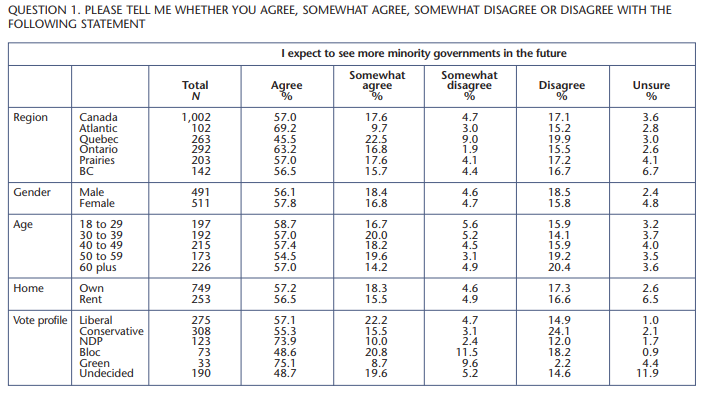

Paradoxically, while four Canadians in five would like to see a majority, three Canadians in four “expect to see more minority governments in the future.” In the Nanos Research poll, 57.0 percent of respondents agree with this statement, and another 17.6 somewhat agree, for a combined total of 74.6 percent. Just 17.1 percent disagree, while another 4.7 percent somewhat disagree, and 3.6 percent are unsure.

Surprisingly, in Quebec, the province whose support of the Bloc is the main reason for minority government, only 45.5 percent agree they expect to see more minority governments, while another 22.5 percent somewhat agree. In Quebec, 19.9 percent disagree and another 9.0 percent somewhat disagree. Four Ontarians in five expect to see more minority governments — 63.2 percent agree with the statement, while another 16.8 percent somewhat agree. In the Atlantic, 78.9 percent agree or somewhat agree with the expectation of more minority governments, while on the Prairies the combined number is 74.6 percent, and it is 72.2 percent in BC.

In other words, Canadians strongly prefer majority governments, but are resigned to minority governments, at least in the near term.

Looking ahead to the current fall session, half the Canadian population thinks it will “be effective” (15.2 percent) or “somewhat effective” (34.2 percent), while about four Canadians in 10 believe it will “be ineffective” (23.4 percent) or “somewhat ineffective” (18.2 percent). The remaining 9.1 percent are unsure. In essence, Canadians are fairly evenly divided about the effectiveness or ineffectiveness of a minority House.

Finally, we asked Canadians which of the federal party leaders, irrespective of their own voting preferences, “has the personal skills to effectively manage a minority government.”

And here Stephen Harper has the advantage, with 32.8 percent nationally, compared to 23 percent for Michael Ignatieff, 14.4 percent for NDP Leader Jack Layton and 5.9 percent for Gilles Duceppe of the Bloc.

On this key leadership question, Harper leads Ignatieff by noticeable margins in all regions of the country except Quebec, where Harper’s leadership scores have gone south since the last election. In Quebec, Ignatieff is seen as best qualified to run a minority government at 29.7 percent, Layton is second at 19.1 percent and Harper trails at 18.1 percent, an unimpressive score for a sitting prime minister on any leadership question. Duceppe is at 18.0 percent in Quebec.

Clearly, though Harper’s leadership standing vis-aÌ€-vis that of his opponents in the rest of Canada is in good shape, he needs to pull up his scores in Quebec if he hopes to maintain or increase the 10 seats the Conservatives hold there, whenever the election is called.

And on that issue, Canadians are quite clear — they don’t want one this fall.

Photo: Shutterstock