No less a personage than Henry Kissinger has said that 2009 would be the year the world finds new ways to manage complex transborder problems that affect us all, by making emerging and important new players on the international scene part of the solution.

The developed countries that have dictated the rules since the creation of the postwar international system now recognize the decisive shift of power to a host of emerging economies that insist on political representation. The old establishment clings to the vain hope that just enlarging club membership will be enough, and that everybody will still play by the old club’s rules, recalling the observation of Principe Don Fabrizio in Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa’s The Leopard, about the advent of democracy in 19th-century Sicily, “If we want things to stay as they are, things will have to change.”

More has to change than the establishment thinks. China, India, Brazil and Mexico won’t be appeased by just a seat at the table. We all have to be prepared to listen and, when possible, act.

But we shall need to act differently. Anne-Marie Slaughter (now in charge of policy planning in the US State Department) recently wrote about “power in the networked century” in Foreign Affairs. She quoted psychologist Carol Gilligan, who almost 30 years ago wrote about “differences between the genders in their modes of thinking. She observed that men tend to see the world as made up of hierarchies of power and seek to get to the top, whereas women tend to see the world as containing webs of relationships and seek to move to the center.”

Slaughter observes that “the two lenses she identified capture the differences between the twentieth-century and the twenty-first-century.”

This changed, more crowded, more complex and yet more diffuse 21st-century landscape imposes stark challenges for Canada. It is widely assumed that Canadian influence and prominence on the world stage will necessarily shrink, helped along by a Canadian government uninterested in very much about the outside world.

But an alternative scenario can see the new landscape favouring Canada. If Canada can repossess and reinvigorate its talents and capacity for international diplomacy, it can move to the centre of the global web and become a go-to country in the search for new ways of resolving vexing international issues. Slaughter emphasizes that “in this world, the measure of power is connectedness.” Much of Canada’s connectedness has to do with international civil society, NGOs and research webs. Canada had a lot of experience a decade ago working with NGO networks supporting a land-mines convention and other successful human security initiatives. It is time to draw again from the networks to get civil society’s takes on the decisive issues confronting the world today.

Next year offers Canada a special opportunity to make a crucial difference. The new G20 for economic issues will have a sort of proxy Canadian co-chairmanship in 2010. And Canada is seeking election next year to the United Nations Security Council (UNSC).

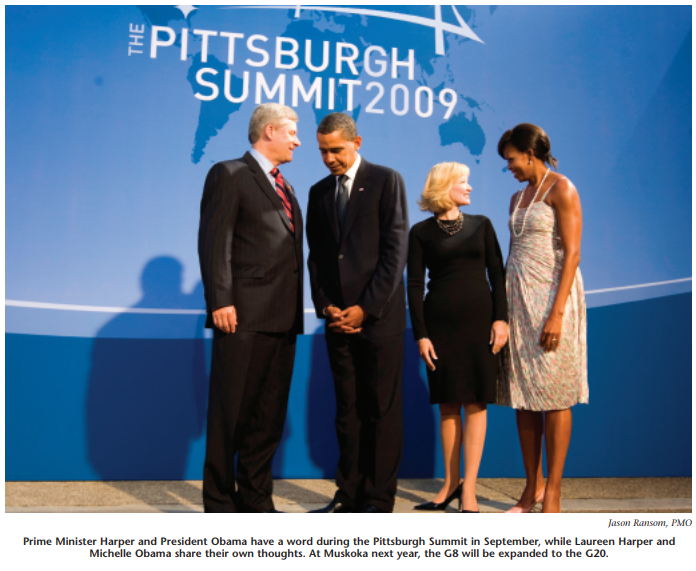

These pages have carried a debate over scrapping the summits of G8 countries in favour of the G20, which was in fact Paul Martin’s proposal. That debate has now been overtaken by the agreement at the G20 summit in Pittsburgh in September to absorb the G8, beginning with the G8 that Canada is scheduled to host in 2010, in Toronto’s pleasant Muskoka cottage country. It will probably be the last G8 summit, a warm-up and sideshow to the G20 under Korean chairmanship, which Stephen Harper will somehow co-administer, also to take place in Canada as the transition occurs.

The present Canadian government has been dragged into this, if not kicking and screaming, at least with whimpers of protective unhappiness. There are a stable of officials for whom G8 membership confers a clubby exclusivity. They like operating in a heavier weight class than the numeric values of our economy would merit. Staffers in the Prime Minister’s Office informally point to officials as the stumbling block. Off the record, officials finger the PM himself as being the leading G20 skeptic.

The question is now academic, although the Canadian side still suggests that as economic questions migrate to the G20, the G8 will retain an afterlife as a separate entity, possibly for international peace and security issues on which the democratically and financially like-minded G8 countries, even with Russia’s Potemkin democracy, are more apt to be able to reach consensus than are the G20. On democracy, the G20 has unequivocally non-like-minded members such as China and Saudi Arabia, as well as several other countries, such as India, Mexico and South Africa, that, because of a past history of interference in their affairs, are quite emphatic on issues of national sovereignty, making it unlikely that the G20 will reach consensus on invasive issues like tougher targeted sanctions on Myanmar or Iran.

But the G8 won’t be saved for peace and security issues. Indeed, it is unlikely to survive at all, because its added value isn’t sufficiently apparent to keep it on the world leaders’ already overbooked travel itinerary. Only its most marginal members, Canada and Italy, really seemed to care. Japan argued against the G20 just to keep regional rival China out of the mainstream of world discussion, but that game is over.

Much of Canada’s connectedness has to do with international civil society, NGOs and research webs. Canada had a lot of experience a decade go working with NGO networks supporting a land mines convention and other successful human security initiatives. It is time to draw again from the networks to get civil society’s takes on the decisive issues confronting the world today.

Prime Minister Harper doesn’t seem very attracted to the United Nations, but President Barack Obama, in a transfer of traditional roles, has higher hopes than his predecessor, George W. Bush, or Canadian Conservatives that the UNSC can be made to work on major issues of international peace and security. It is no coincidence that Obama personally chaired a UNSC session during the September heads-of-government sitting of the General Assembly. If he succeeds in its revalidation, the Security Council could re-emerge as the locale of legitimacy for decision-making on peace and security issues, as the UN Charter intended. Only briefly, at the end of the Cold War, has the Security Council been able to fulfill this role with anything like effectiveness.

Over time, in the UN’s 65 years of existence, its capacity to deliver peace and security has been pretty pathetic, largely because it was stymied by Cold War divisions and vetoes blocking decisive action on most issues. But during a few years at the end of the Cold War, the USSR/Russia cooperated with the US, France and the United Kingdom to make the system work as the Charter had intended, on such issues as authorizing a UN coalition to oust Saddam Hussein from Kuwait, with China remaining noncommittal but generally unopposed. President Obama’s plan relies on the success of his hopes that by engaging the Chinese and Russians strategically, he can persuade them to transit again from a spoiler role to one of creative collaboration in a cooperative approach to international peace and security.

The quid pro quo will be the need for that approach to take more account of the multiple perspectives of a more polycentric world.

The council needs also to broaden its traditional mandate. International security is no longer considered to be just a matter of peace or war, of military conflict between states. Nonstate actors are as much a threat to international peace and security as states are themselves. Transnational threats such as natural disasters, drug trafficking, climate change, economic underdevelopment, migration and desertification all affect human security and the security of states. For violence within states, the Canadian-led Responsibility to Protect initiative empowers the council in principle to authorize international intervention within a single state in cases of apparent genocide and mass atrocity.

But agreement on a broader mandate is hindered by the inability to resolve the tortured question of expanding the Security Council’s membership.

The Security Council’s membership is ludicrously archaic, with permanent memberships and vetoes for the P5, the five Second World War “powers” (which are also the original nuclear weapons states), and rotating two-year memberships for 10 others, nominated by regional groups or, if a group fails to reach agreement, elected by all states that are members of the UN. The “others” obviously include several of the emerging countries that the G20 has been created to accommodate on economic issues, as well as Germany and Japan. All take badly the outdated and unmerited special status of France and Britain. In a sane system, France and Britain would be negotiated downward and others upward but in an attitude that is frankly scandalous, the two once-colonial powers refuse to diminish their prerogatives. Others, such as Italy, are equally unrealistic in their membership ambitions. Reform, therefore, has been impossible to achieve, as every formula for change offends the interests of some important UN clients. So we are apt to be stuck with what we have for some time.

The key to making the existing UNSC effectively responsible is likely still to be found in searching for consensus among the P5. But what the council has to do, if it can’t reform its membership, is find a way to consult systematically with key nonmembers, to open up a process that P5 members have historically kept to themselves.

This has been an enduring Canadian preoccupation every time we have served on the council, roughly for one two-year term each decade since the UN’s founding, a frequency we and the world found fitting because our contributions and beliefs matched our participation.

Can we make that case today?

There appears to be a consensus among the commentariat in Canada that the Harper government has shrunk Canada’s international profile. “Le Canada: pays ou village?” asks Denise Bombardier. “Stephen Harper semble faire preuve d’une absence d’intérêt pour tout ce qui n’est pas Canadian.”

Harsh, but supported by others. Carol Goar: “Regrettably, Canada has sidelined itself. It was once a pillar of the United Nations. Now it is a bit player. It was once seen as a country that punched above its weight globally. Now it is barely in the ring.” Or Jeffrey Simpson: “Canada has so little to say.”

We were a mainstay of UN peacekeeping, which Lester Pearson basically created. Since 1948, 114 Canadians have died in UN peacekeeping duty. But we have fallen from 3rd to 57th on the list of contributors. Only 55 Canadian soldiers now serve among the 93,000 peacekeepers in 17 current UN peacekeeping operations.

There are substantive reasons for the apparent decline. Peacekeeping is a viable approach only if there is a negotiated peace to be kept. Today’s challenges are as much in the zone of peace-making, most prominently for Canada through the NATO engagement in Afghanistan, which is not a UN mission but is authorized by the UNSC (as the US-led invasion of Iraq was not, having failed to win the support of 10 of 15 members of the Security Council).

The costs to Canada of the deployment to Kandahar province have been heavy: 132 Canadian lives at this writing, and billions of dollars. The army is chewed up.

But the opportunity costs preventing other deployments within the UN and even many diplomatic initiatives elsewhere will diminish as we approach the end of Canada’s combat role in 2011.

There is a host of other issues on which to rebuild the Canadian reputation for serious engagement to promote international peace and security. The following are some examples.

Unquestionably, the threat of proliferation of nuclear weapons is an overarching menace to the world. The good news is that weapons of mass destruction verification has made important normative, technical and institutional strides since the United Nations Special Commission worked rather raggedly in Iraq. Its successor, the United Nations Monitoring, Verification and Inspection Commission, under Hans Blix, actually got the job done right, even though the Bush administration disregarded its findings that Iraq had no current nuclear arms program. Today, Russia and China share the West’s wish to stop proliferation, including in Iran. Working to strengthen the inspections regime under the International Atomic Energy Agency should be a natural fit for Canada.

So are the nuclear build-down issues Obama is emphasizing. The review of the Non-Proliferation Treaty and reinforcing the international comprehensive test ban regime are also revived priorities for which Canada had long been an active proponent. Our credentials as a country that stopped deploying nuclear weapons are impeccable, but we have left the field to others.

The UN’s capacity to intervene to halt mass atrocities under the Responsibility to Protect title that Canada laboured long and hard to secure is still mostly theoretical. Raising a well-equipped and mandated UN force is a time-consuming and laborious international negotiation, deeply frustrating while people are dying. The notion of a standing multinational UN force has long been discussed but needs credible leadership in order to turn into reality. Canadian leadership would be timely and welcomed by the world’s powers.

Conflict and terrorism won’t go away. Military action is seldom decisive in defeating armed groups. The Rand Corporation has identified 648 groups that abandoned terrorism between 1968 and 2006 — only 7 percent by military defeat. The others were absorbed into the political process. But the process needs players such as Canada to serve as catalysts and honest brokers, a role the larger powers usually cannot play.

Canada under the Conservatives is becoming instead more known for gesture politics, bans on talking with groups like Hamas and walkouts at the UN when unpleasant people like Ahmadinejad take the podium. These are useless internationally. The world needs countries ready to engage internationally, diplomatically, the way Norway has done, with actors in conflicts, including nonstate actors. The overall reactivation of Canadian foreign policy needs to begin now, or else 2010 will mark a humiliating defeat for our campaign to win election to the UNSC, to complete our record of election every decade since the UN was founded. Three Western countries — Germany, Portugal and Canada — are competing for two “Western” swing seats. Once, we could expect support from many African countries. That was before we downgraded Africa in our development priorities. We even drew EU support over EU competition — visas and seals and the rest of the Canadian small agenda dampens that possibility as well. This time, the election of Canada is by no means assured.

Does the mandate of the G20 offer Canada equivalent possibilities to add real value to international crisis prevention and management? Prime Minister Harper seems to think the G20 will be content to assume accountability for past decisions of the G8, as well as taking note of Canada’s orderly economic management. Obviously, the somewhat resentful leaders of the major emerging countries are looking to decision-making on the real and future major issues, not to a past in which they were not participants.

After the first G20 meeting in Pittsburgh, President Obama credited participants with “a level of tangible, global economic cooperation that we’ve never seen before.” The general idea is that the G20 will annually agree on broad objectives for economic growth and then task the International Monetary Fund with carrying out an assessment or peer review of each country’s compliance.

Three Western countries — Germany, Portugal and Canada — are competing for two “Western” swing seats. Once, we could expect support from many African countries. That was before we downgraded Africa in our development priorities. We even drew EU support over EU competition — visas and seals and the rest of the Canadian small agenda dampen that possibility as well. This time, the election of Canada is by no means assured.

It is a problem that there are no sanctions for non-compliance. Let’s face it: the G8’s commitments on such undertakings as aid to Africa have been ludicrously undersubscribed.

The more specific and immediate focus of the Pittsburgh summit was on necessary lessons of the financial crisis of the last year. The meeting called for much tighter regulation over financial institutions, including especially their handling of new and complex financial “products” like credit swaps, and excessive executive pay.

The financial framework’s global dilemmas include the huge imbalances that exist between export-dominant China, India and Germany, on the one hand, and the debt-laden big consumer, the United States, on the other. A resolution would include counterpart commitments: the United States would need to address its huge budget deficit, increase its savings rate and try to reduce consumer demand and thereby its trade deficit, all without dampening growth. The export giants would need to promote more consumer spending and direct investment at home, and rely less on exports. To pull it off would require a very strong G20.

Even more difficult, and possibly more important in the long term, are other major substantive and deeply divisive issues that go beyond the confines of one box or another.

The G20 can’t arrogate to itself the right to close a deal outside of the designated universal bodies where the whole world participates, several of which are preoccupied by the enduring gaps between richest and poorest peoples. A problem with the G20’s representation is an absence of the world’s poorest countries — understandably, since G20 membership is meant to include the top 20 economies. But the G20 could serve as a key focus group to catalyze reduction of some of the adversarial walls among developed, developing and emerging economies, which could then be taken to the wider universal forums.

Barry Carin and Gordon Smith work at the University of Victoria to spearhead an international effort among scholars, institutes and former and current officials to identify how a G20 could tackle some of these and other issues effectively.

Nearly two-thirds of Canadians identify climate change as the “most dire threat to humanity.” But international agreement on who needs to do what to meet the threat is nowhere apparent.

Carin candidly says he can’t see how a world climate change deal can emerge on carbon countries’ emission terms alone: the transfers from developed to developing to pay for abatement technologies will be too great, and the costs of lower growth in China would be difficult for the Chinese to swallow politically. Similarly, he joins many who can’t see the outlines of a global trade deal ever emerging from the dormant Doha Round.

But why couldn’t there be trade-offs across issue areas? Part of the compensation for carbon emission abatement in emerging economies might come from the removal of enduring barriers to access to developed markets for developing countries’ agricultural exports.

Of course, this kind of big-picture, multifaceted, long-range problem-solving exercise really stretches the institutional art form.

At summits as we know them, conditions aren’t very propitious for coaxing out such trade-offs on huge and very political topics. This isn’t Dayton or Camp David. There are too many people, too little time. The photo from Pittsburgh’s one-day show of set speeches shows 53 people at the big round table with a couple of dozen more officials behind.

All this argues for some kind of continuous preparatory and consultative process that will need empowered leadership of a kind that doesn’t come easily from a part-time rotating presidency. One of the reasons the G8 became beside the point is that the preparatory process became bureaucratized and compartmentalized. Leaders came together with only bromidic precooked declarations to approve. The G20 has to do better, but it isn’t evident how to do this and handle the cross-cutting major issues.

Carin envisages the detachment from national governments of key top officials to form an elite team from present, recent and future presidencies of the G20 to consult, prepare and catalyze bargaining. But best and brightest elites don’t deliver public buy-in. It will take the thorough engagement of political leaders who need to answer to their electorates (and get re-elected). The upside is that participation in a difficult collective undertaking does provide political cover to national leaders for the task of persuading their parliaments (those in the G20 that have them) to go along. But they probably need to name a catalyzing team of those who have worked at the top — Tony Blair, Kofi Annan, Bill Clinton, ex-Spanish prime minister Felipe González Márquez, ex-president Joachim Chissano of Mozambique, Chinese master negotiator Yong Longtu and so on — to work the capitals to prepare the sorts of grand bargains the world has to take on board.

Meanwhile, Carin strongly advocates connecting to the networks among NGOs and research institutes to validate the data and the options and to ensure transparency. It is essential to mobilize civil society for the peace and security and cross-cutting environmental and economic issues. Consultation is important, but getting their input is even more so.

Are Canadian officials and Canada’s political level up to this, or will they just be along for the ride? Can they begin to match and use the ingenuity of scholars and other outsiders and take some of these ideas that are essential to problem solving and governance affecting the planet to the international political market? In a government obsessed mostly with minority-government partisan competition at home, do we have the breadth of vision?

Once again, 2010 will provide a unique opportunity for Canadian leadership of a kind that will win plaudits from others, and that will thereby build influence for Canada. But it will require lifting the Canadian game. There is no reason that Stephen Harper cannot do it, though he will have to change his closed and controlling style. There are high stakes for this country across the political and economic boards. There is also the enduring notion of service to humanity that Canadians were born bred and to take seriously. It needs revival among us.

Photo: Shutterstock