Throughout the three-day policy conference the Liberals held at the end of March in Montreal, Michael Ignatieff sat in the front row with his wife at his side, listening intently and jotting things down in a red moleskin notebook. Meanwhile, off in Liberal-land, groups of dozens, even hundreds, gathered in community centres and university meeting rooms to participate in the deliberations through a dazzling array of blogs, tweets, Skypes, and live televised interaction with the folks in Montreal.

There was certainly plenty to digest. The Liberals had invited a variety of speakers from the worlds of business, academia, the public service and nongovernmental organizations, not necessarily all Liberals, but mostly liberal-minded. There were very sobering assessments of the demographic tsunami about to confront our health care and pension systems — not to mention its effect on economic growth and government balance sheets. And there were many bold policy ideas, from creating a supplemental Canada Pension Plan, to allowing more private health care. The energy and environmental experts pounded out a drumbeat: carbon tax, carbon tax, carbon tax.

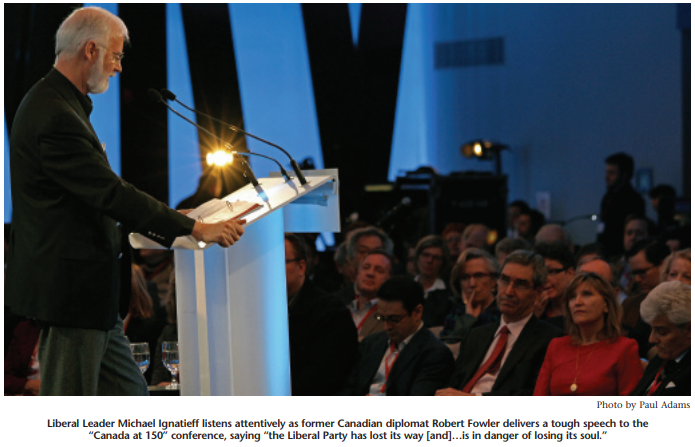

The most startling intervention, however, came at 8:30 a.m. on the last day, as participants were still slurping their coffee, and just a few hours before Ignatieff himself addressed the meeting. Robert Fowler, former senior Canadian diplomat, former ambassador to the United Nations and former al-Qaeda hostage, unleashed a fusillade at the Liberals that seemed like it must have been the product of many long hours of gloomy contemplation.

“I believe the Liberal Party has lost its way, at least in policy terms,” he said to stunned silence in the room. “Indeed, it is in danger of losing its soul…It seems the Liberals today don’t stand for much in the way of principle. I have the impression that they will endorse anything and everything which might return them to power, and nothing that won’t.”

The Liberals, he said, would “shill for votes” rather than build coalitions and promote their traditional values. They had yet to provide Canadians with a “cogent vision,” he said.

All this in the first three or four minutes of a half-hour address that could have been titled “Don’t Get Me Started.” (The speech had been billed, more modestly, as “Africa in 2017 and Canada as Partner.”) Fowler condemned both major parties for the military commitment in Afghanistan and a Middle East policy shaped, as he saw it, in the “scramble to lock up the Jewish vote.”

At a press conference later in the day, Ignatieff averred that he did not agree with “every syllable” of Fowler’s remarks, though it would have been more illuminating to hear precisely which syllables were in dispute.

As startling as Fowler’s speech was, given the occasion, it did draw attention to an equally startling fact about Michael Ignatieff’s leadership of the Liberal Party. He came to the job with a justified reputation as a serious man with serious ideas. In his run for the Liberal leadership in 2006, Ignatieff distinguished himself, if anything, as somewhat impetuous in voicing those ideas (most notably, in favour of a carbon tax and recognizing Quebec as a nation and, at least briefly, taking the view that the Israelis had committed war crimes in southern Lebanon.)

But since Ignatieff became leader, the Liberal Party has distinguished itself for the near complete absence of policy. Very few Canadians — and this includes most parliamentary reporters and senior Ottawa bureaucrats, as well as many Liberal candidates for that matter — could tell you with any precision how the Ignatieff Liberals differ from the Conservatives on any of the great issues of the day: managing the recent recession or the resulting deficit, climate change, the war in Afghanistan, medicare, pensions — the list goes on and on.

At least since William Lyon Mackenzie King elevated ambiguity to the status of a Liberal principle, the party’s relationship with declarations of policy has been an uneasy one. In living memory, the party opposed wage and price control and then imposed them; attacked free trade and then embraced it. Even the vaunted Red Book, drafted in part by Paul Martin, and then fetishized by Jean Chrétien, can be read in retrospect as a catalogue of promises unfulfilled: the renegotiation of NAFTA, national daycare, a rapid increase in immigration, a rejection of the Conservatives’ “unrealistic” goal of eliminating the deficit in five years.

This played to the most negative impulse Canadians have about the Liberal Party: that its only objective is power. When Ignatieff made his most muscular play to force an election in August and September of last year without any clear public objective, he was humiliated by the media, mocked by the government and deserted by the public.

That having been said, many Canadians do see the Liberal Party as embodying identifiable ideals in government as well as on the campaign trail, if not always with perfect consistency: primarily a belief that government has a constructive role to play in complementing the free market and addressing its defects. It is the party of medicare, public pensions, robust employment insurance, and, more recently (at least once the deficit was tamed), national initiatives in research and education, renewed investment in health care, national child care, and the Kelowna Accord.

Confronting a government that dismantled the last two achievements as soon as it came to office, and is gradually demolishing the Liberal-erected edifice of regulatory authorities, you might think that the Liberals under Ignatieff would be spoiling for a fight on policy and principle most days of the week. Indeed, Ignatieff toyed with the idea of a thinkers’ conference early in his leadership, but quickly abandoned the idea. He put forward an interesting blend of patriotism and mega-projects such as high-speed rail and a national energy grid in his book True Patriot Love, then slid it onto a low shelf in the bookcase, out of sight. And he promised at the convention in Vancouver at which his leadership was ratified that he would have a party platform ready by June — June of last year, that is.

One can only assume that when Ignatieff feinted forcing an election in June 2009, or when he went at it more seriously in the late summer, he had a platform in his pocket. Whatever it was, it never did see the light of day.

There are a number of explanations for the Ignatieff Liberals’ aversion to policy. He came to the leadership in the aftermath of an election defeat, a coalition fiasco, and in the midst of the world financial crisis. He did not want to defy the international consensus for stimulative spending embodied in the Tories’ 2009 budget. (Indeed, in the months immediately after the Tory budget, Ignatieff got his longest sustained bump in the polls.)

Furthermore, the Liberals learned — I would say “overlearned” — the object lessons of Stéphane Dion’s Green Shift. Those lessons were: never utter the words “carbon tax,” and never give the Conservatives a big fat policy target to shoot at.

What happened was that the Liberals made a tactical decision that their best route back to power was not to offer Canadians an alternative vision of how Canada should be governed, but simply to allow the government to defeat itself. You can see the logic in this, and there are certainly historic precedents for its success. But in retrospect, it was a disastrous decision.

As citizens, we were left without a clearly articulated critique of the Harper government or any idea of what a different government making a different set of choices might look like. The media dynamics, unfortunately, don’t allow the other parties to play this role, however hard they try.

But even from a narrowly Liberal perspective, it didn’t work either. It left the media without any substance to chew on, and because news abhors a vacuum, reporters did stories on Ignatieff’s leadership and the Liberals’ parliamentary tactics. Those tactics, crudely put, were to avoid an election at all costs, except in the months when the Liberals were trying to force one to occur.

This played to the most negative impulse Canadians have about the Liberal Party: that its only objective is power. When Ignatieff made his most muscular play to force an election in August and September of last year without any clear public objective, he was humiliated by the media, mocked by the government and deserted by the public.

Let’s look back to the late summer of 2009. The Liberals had been level-pegging in the polls with the Tories through the summer, but the public’s reaction to the election threat was to stampede to the Tories. In EKOS’s tracking poll, the Conservatives hit 41 percent in mid-October, their highest number since the coalition debacle, well above their 2008 election performance, and clearly in majority-government territory. The Liberals nose-dived.

The Conservatives, of course, did not sustain this heady level of support. In the months that followed they hit some choppy waters. Their performance at Copenhagen was an embarrassment. Then, they mishandled Richard Colvin’s revelations about the abuse of Afghan detainees. Stephen Harper compounded that mistake by proroguing Parliament.

This was the perfect test of the thesis that governments defeat themselves: a government besieged with problems, led by a man the public has never warmed to. In the EKOS tracking poll, the Conservatives fell a full ten percentage points off their mid-October peak. By the time of the Liberal policy conference, they had been stabilizing at eight or nine points off their peak.

So, what of the Liberals? At conference time, they had recovered just two percentage points since their mid-October trough. The Liberals were within the margin of error of where Stéphane Dion had led the party in the 2008 election, the worst in terms of popular support in the party’s history.

In January, at the height of the prorogation controversy, the Liberals had been winning over at best half of the Canadians then deserting the Tory party. By the end of March they appeared to be drawing virtually none. Bizarrely, in the first three months of 2010, no party commanded the support of even one-third of Canadians – a situation that may be unprecedented in Canadian political history. As weak as the Harper Tories had become, it was doing the Liberals virtually no good.

What this means is that the Liberal Party has no power to rally the genuine anti-Harper sentiment that exists in the country. Most Canadians who give up on the Tories go right past the Liberals to the NDP, the Bloc or, in particular, the Greens. At the moment, there is absolutely no “strategic vote” benefiting the Liberals, unlike in 2004, when Paul Martin managed to stave off defeat by raising fears about Stephen Harper and collapsing the NDP vote.

There are various explanations for this utter demagnetization of the Liberal Party, but one of them, surely, must be the fact that it has not differentiated itself from the Conservatives in terms of policy. The Conservatives’ greatest strength at the moment is their reputation as competent economic managers (a reputation they owe in part to the lack of effective opposition). Although less than one-third of Canadians support the Tories, in most weeks a plurality thinks the government is going in the right direction, and even more think the country is headed in the right direction.

At a time when the economy is the most pressing issue for most Canadians, and they feel the Conservatives have managed reasonably well, why would they rally round the Liberals, who have not staked out an alternative policy and whose leader is less experienced than the incumbent prime minister?

The conference in Montreal was presumably the beginning of an attempt by the Liberals to differentiate the party, and some of the reporters covering the weekend certainly saw it that way. Indeed, it highlighted the Liberals’ tolerance for provocative views and their openness to competent and contemporary management. Ignatieff has seemed somewhat more comfortable in his skin since Chrétien veteran Peter Donolo took office a few months ago, and his closing speech to the policy convention reflected that. There was no prepared text for distribution to the media, because he was working on it himself till the last moment, we were told, and it seems fair to take that at face value. This was Ignatieff being Ignatieff, and expressing his own convictions about where the Liberal Party should head.

Ignatieff told the convention: “I don’t recall one instance this weekend when someone said, here’s the problem, the solution is a big expensive government program. Didn’t hear it. Didn’t hear it.”

He obviously hadn’t been listening as carefully as he had appeared to have been. Indeed, the speech seemed strangely divorced from the conference that preceded it: dramatically shrunken in scope and ambition.

Ignatieff did, however, spell out specific objectives for a future Liberal government in terms of social policy, some of which did seem to imply big programs:

- A “pan-Canadian learning plan”; G Early childhood learning and child care for every family that wants it;

- A university education for every student who gets the grades;

- Illiteracy programs and language training for immigrants;

- Closing the gap between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal educational attainment;

- Extended employment insurance benefits for people looking after elderly parents; and

- A national strategy for preventive health care led by the federal government and aimed at reducing the costs of our health care system

(In a subsequent op-ed in the Sun newspaper chain, Ignatieff added the possibility of a supplementary Canada Pension Plan.)

Most Liberals would find it hard to object to these goals, though it was weak tea compared with the strong drink that had come from speakers earlier in the conference.

David Dodge, the former governor of the Bank of Canada and onetime architect of the Chrétien-Martin deficit elimination plan, had called on Liberals to have an “adult conversation” about the skyrocketing costs of health care, and the “stark and unpalatable choices” they implied. The options, he said, were degraded public coverage, a two-tier health care system, higher taxes, or ballooning public debt.

From the floor of the conference, Frank McKenna had called for a “catastrophic drug care” program, and hinted at loosening the Canada Health Act to allow provinces to experiment more with different systems of health care delivery, implying, perhaps, a greater private sector role in at least some provinces.

One speaker had called for a supplementary Canada Pension Plan with compulsory participation. Another speaker suggested the elimination of long summer vacations for students, and one proposed the elimination of “boutique tax credits,” and perhaps an increase in the GST, to pay for social programs.

And then there was the percussive plea for the carbon tax Ignatieff had himself once advocated and the party had championed under Dion. Not a single participant at the conference contested the importance of a putting a price on carbon (though one repeatedly raised the issue of its political salability). But a carbon tax is plainly beyond the Ignatieff Liberals’ courage threshold.

Moreover, even those social policy objectives Ignatieff did enumerate turned out to be subject to a higher priority: eliminating the deficit. By making the deficit his overriding priority, he made jobs, education, health care, day care, pensions, and so on, secondary: a wish list for another day.

“How do we pay for this?” he asked the conferees. “We can’t be a credible political party until we have an answer to that question…Unless we can convince Canadians that we are going to get them out of the [current $50 billion plus deficit] they are not going to listen to anything we say.”

More specifically, Ignatieff pledged to get the deficit down to 1 percent of GDP within two years of taking office. This figure, which would likely be in the $17-$18 billion range, is not as daunting as it might appear. It is in the same neighbourhood as the “cyclical deficit” forecast by Finance Minister Jim Flaherty, and the “structural deficit” projected by the Parliamentary Budget Officer, Kevin Page. Page thinks it is possible to get there with a combination of expired stimulus programs, the expected economic growth and modest spending restraint. (After that, however, unlike the government, he thinks there need to be significant spending cuts or tax increases to get the deficit to zero.)

After reaching this initial target, Ignatieff pledged, a Liberal government would continue to reduce the deficit each year, along an unspecified timetable, until it reached zero.

In making the pledge, Ignatieff essentially ratified the Conservatives’ emphasis on the primacy of deficit elimination, at least starting next year, and continuing through the four-year term of a Liberal government.

Where Ignatieff’s plan, as outlined in the speech, differs from that of the government, is in its approach to corporate tax cuts. Ignatieff told the convention he was “passionate” about corporate tax cuts. (Well, who isn’t?) However, he said a Liberal government would not proceed with further planned reductions in corporate taxes until the deficit is eliminated. This would yield the government in the neighbourhood of $5 billion per year, according to the Liberals. This amount, Ignatieff said, would be used “to reduce the deficit and invest in the future.”

To put some perspective on this, $5 billion is less than 2 percent of the current federal budget. Even if it were used exclusively for “investment,” which does not appear to be Ignatieff’s intention, it would not be enough to fund a national daycare and early child learning program, as well as a preventive health care program robust enough to have an effect on soaring health care costs — let alone the other social policy objectives outlined in his speech. Ignatieff also said that no new spending would be undertaken unless funds could be specifically identified for that purpose without raising the deficit. This would presumably mean deep expenditure cuts elsewhere (in an environment, remember, where the government would already be trying to cut the deficit to zero), or it would mean tax increases. Quite likely it would actually mean the Liberals would make no serious attempt to achieve the array of social policy goals Ignatieff is advocating.

When I confronted one of Ignatieff’s advisers with this logic, I was accused of “asking him to write a budget,” which apparently was off limits.

Ignatieff may imagine that there is another way out of this self-imposed dilemma, an idea on which he put great emphasis in his speech. “We are not a big government party; we are the party of the network,” he declared, apparently meaning that his government would bring together different levels of government, along with business and nongovernmental organizations, to resolve problems.

He even talked about something he dubbed “the power of convening.” He called this “a humble conception of political authority.”

This is precisely one rung up the ladder from complete nonsense. The rung has a name: wishful thinking. And Ignatieff laid it out plainly elsewhere in his speech. Discussing the cacophony of Canadian voices at the Copenhagen conference on climate change, he chastised Stephen Harper, and said that there was an “easy” alternative: “Pick up the phone and say we’re going to a conference…let’s try and work out some kind of common position.”

Alberta, this is Quebec. Quebec, have you met Alberta? Now let’s sort this out. I’ve got a plane to catch.

Ottawa can certainly convene a meeting. But as the provinces face the challenges of health care, education and day care — all areas primarily within their jurisdiction — it is hard to imagine Ottawa playing much of a role without putting significant money on the table.

If Ignatieff were to become prime minister, the “networking” that would likely consume most of his energies would be with the opposition parties in a minority parliament.

The Liberals say that the ideas thrown up by the policy conference will now be considered by a series of regional party meetings, all of which would feed into the formulation of a party platform, which Ignatieff promised would be ready (though not necessarily for release) by September.

But what Ignatieff has begun to outline so far is really a variation on the existing Conservative fiscal agenda, dressed up with a social policy wish-list that is unattached to any realistic funding plan.

The Liberals’ election hopes may now hang on the ability of a leader who has never led a national campaign and who is running on a nondescript policy program, to come from behind and beat a battle-tested incumbent in a period of economic recovery.

Photo: Art Babych / Shutterstock