Section 91(24) of the Constitution Act, 1867 provides the Parliament of Canada with “exclusive Legislative Authority” in relation to the classes of subjects “Indians, and Lands reserved for the Indians.” There is little evidence to indicate why the Fathers of Confederation opted to assign the federal government exclusive legislative authority in this domain, but the most plausible explanation appears to be the nation-to-nation relationship that characterized dealings between Aboriginal peoples and the Crown in British North America since contact. From the outset of Crown-Aboriginal relations in British North America, the Crown found itself responsible for protecting Aboriginal peoples and their lands from the encroachment of settlers and exploitation by colonial governments. A renowned articulation of this responsibility and relationship is found in the Royal Proclamation of 1763, wherein King George III decreed that Aboriginal people living under British rule “should not be molested or disturbed” by colonial governments or settlers with respect to lands “reserved for them.” The Crown responsibility to ensure the welfare and protection of the Aboriginal peoples under its rule emanated from the perception of them as “victims of colonial expansion” and from the belief that “a more distant level of government would better protect Indians against the interests of the local settlers.” At Confederation, this responsibility of the British Crown succeeded to the Crown in right of Canada by virtue of section 91(24) of the Constitution Act, 1867.

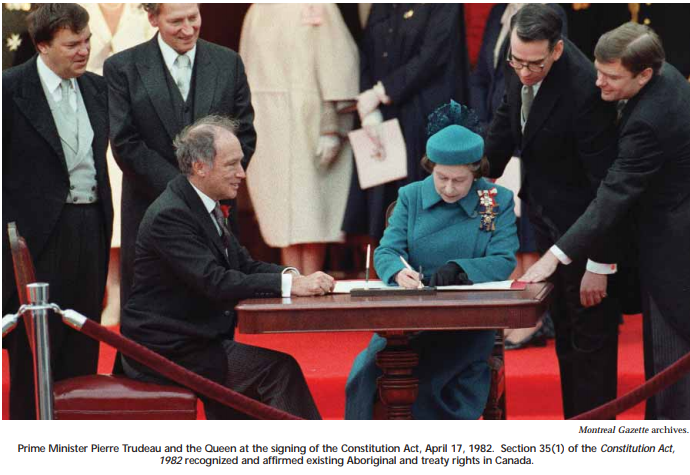

Until 1982, section 91(24) was the only reference to the Aboriginal peoples of Canada in the Canadian Constitution. The enactment of section 35(1) of the Constitution Act, 1982 recognized and affirmed the Aboriginal and treaty rights of the Aboriginal peoples of Canada existing in 1982. The Supreme Court of Canada first addressed the relationship between section 91(24) and section 35(1) in the 1990 decision of R. v. Sparrow. Acknowledging that the exclusive federal power to legislate in relation to “Indians, and Lands reserved for the Indians” continued after 1982, the Supreme Court of Canada held that this power “must, however, now be read together with s. 35(1).” This requirement led the Court to acknowledge that s. 35(1) mandates that the power of the federal government pursuant to section 91(24) be reconciled with the federal duty “to act in a fiduciary relationship with respect to aboriginal peoples” that is “trust-like, rather than adversarial.”

Since Sparrow, an increasingly broad conception of reconciliation emerged as the fundamental objective of section 35(1). In Mikisew Cree First Nation v. Canada (Minister of Canadian Heritage), Justice Ian Binnie held that “the fundamental objective of the modern law of aboriginal and treaty rights is the reconciliation of aboriginal peoples and nonaboriginal peoples and their respective claims, interests and ambitions.” Charlotte Bell argues that “the scope of section 35 may not be sufficient” to facilitate such an all-embracing form of reconciliation; the ability to do so may require turning to another constitutional source. This paper proposes that the duty of the federal Crown inherent within section 91(24) of the Constitution Act, 1867 to provide for the welfare and protection of the Aboriginal peoples of Canada is that source. The broad and historical duty underlying section 91(24) mandates the federal government to lead the way in pursuing the reconciliation of Crown sovereignty with the prior inhabitation of the Aboriginal peoples of Canada. This mandate comes into clearer focus when the broad responsibility underlying section 91(24) is harmonized with the affirmation and recognition of Aboriginal and treaty rights contained in section 35(1).

Section 91(24) of what was then known as the British North America Act contains two distinct classes of subjects: “Indians” and “Lands reserved for the Indians,” not Indians on Lands reserved for the Indians. Therefore, section 91(24) applies to Aboriginal people generally, whether on or off reserve, status or non-status. Section 91(24) also incorporates the Inuit, but it remains unresolved whether the Métis people of Canada fall under the authority of section 91(24). The Supreme Court of Canada has held that the class of subjects “Lands reserved for the Indians” in section 91(24) “encompasses not only reserve lands, but lands held pursuant to aboriginal title as well.” In keeping with the historical origins of the provision, the Court has also acknowledged that the federal Crown bears unique “responsibilities flowing from s. 91(24) of the Constitution Act, 1867.” In its broadest terms, the federal Crown alone bears the responsibility “to provide for the welfare and protection of native peoples” in Canada. This broad federal responsibility embedded within section 91(24) represents the continuation of the nation-to-nation Crown-Aboriginal relationship that existed prior to Confederation.

Bradford Morse argues that section 91(24) has “had a profound impact upon the evolution of the Crown-Aboriginal relationship since 1867.” The inclusion of section 91(24) at Confederation sustained the presumption “that all of the major responsibilities that had been held exclusively by the Colonial office, including obligations under pre-Confederation treaties and the power to negotiate new ones, were simply transferred to the government of Canada.” In essence, the inclusion of section 91(24) embodied the assumption by the federal Crown of the responsibilities formerly held by the British Crown toward Aboriginal peoples, including the provision for their welfare and protection. From 1867 to 1982, the utilization of section 91(24) ultimately depended on the will of Parliament. With the enactment of the Constitution Act, 1982, however, constitutional supremacy supplanted parliamentary supremacy in Canada. The inclusion of section 35(1) in the Constitution Act, 1982 means that this paradigm shift also governs the determination of Aboriginal and treaty rights in Canada after 1982.

Prior to 1982, the Aboriginal and treaty rights of the Aboriginal peoples of Canada were vulnerable to governmental extinguishment by way of clear and plain legislative action. With the enactment of the Constitution Act, 1982, such rights received constitutional protection by virtue of section 35(1): 35. (1) The existing aboriginal and treaty rights of the aboriginal peoples of Canada are here-by recognized and affirmed. Immediately following the enactment of section 35(1) as part of the Constitution Act, 1982, the import of the provision was unclear. A series of First Ministers’ Conferences during the 1980s failed to clarify the content of the provision. In 1990, the Supreme Court of Canada interpreted section 35(1) for the first time in R. v. Sparrow. Speaking to its content and the scope of its protection for Aboriginal and treaty rights, the Court also assessed the effect of section 35(1) on section 91(24) of the Constitution Act, 1867:

Rights that are recognized and affirmed are not absolute. Federal legislative powers continue, including, of course, the right to legislate with respect to Indians pursuant to s. 91(24) of the Constitution Act, 1867. These powers must, however, now be read together with s. 35(1). In other words, federal power must be reconciled with federal duty and the best way to achieve that reconciliation is to demand the justification of any government regulation that infringes upon or denies aboriginal rights.

In the Sparrow decision, the Supreme Court of Canada made a point of discussing the impact of section 35(1) on the exclusive legislative authority of the federal government over “Indians, and Lands reserved for the Indians” in section 91(24). In Sparrow, this meant that the exclusive federal power to legislate in relation to Aboriginal people now had to be reconciled with the federal duty to act in a fiduciary relationship with respect to the Aboriginal peoples of Canada. This reconciliation dictates that by virtue of section 35(1), the meaning of section 91(24) must transform itself from a constitutional grant of legislative authority permitting Parliament to do as it wishes in regards to Aboriginal peoples and their lands, to the constitutional vehicle for accomplishing reconciliation between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal peoples. This transformation is conceptually achievable by virtue of the broad duty that underlies section 91(24) to ensure the welfare and protection of the Aboriginal peoples of Canada. In essence, the Sparrow decision dramatically recast the constitutional understanding of “welfare and protection” in relation to the Aboriginal peoples of Canada to mean the determination, recognition and affirmation of their constitutionally protected Aboriginal and treaty rights.

There is little evidence to indicate why the Fathers of Confederation opted to assign the federal government exclusive legislative authority in this domain, but the most plausible explanation appears to be the nation-to-nation relationship that characterized dealings between Aboriginal peoples and the Crown in British North America since contact.

The Court in Sparrow held that section 35(1), at the very least, provides “a solid constitutional base upon which subsequent negotiations can take place” to determine and recognize the still unproven Aboriginal rights embedded within the provision. While the Court states that section 35(1) provides the constitutional base for Crown-Aboriginal negotiation, it does not go so far as to identify section 35(1) as the constitutional mechanism to see the processes of negotiation carried out. Indeed, the Court does not identify a constitutional source of governmental power that occupies this role. However, it appears that section 91(24) is that source. Negotiations consecrated to determine Aboriginal and treaty rights fall under the classes of subjects “Indians, and Lands reserved for the Indians,” and therefore under the exclusive legislative jurisdiction of the federal government. Furthermore, reading section 91(24) together with section 35(1) illustrates that the former provision must also serve as the constitutional vehicle by which Crown-Aboriginal negotiations will transpire. One must recall that section 35(1) delivers the constitutional base for negotiation; it gives Aboriginal peoples a constitutional bargaining chip at the negotiating table, but not the negotiating table itself. As the provider for the welfare and protection of Aboriginal peoples and the level of government with the appropriate legislative jurisdiction, the federal Crown by virtue of section 91(24) is obligated to fulfill the promise of section 35(1) through honourable negotiation, so that the Aboriginal and treaty rights of the Aboriginal peoples of Canada are “recognized and affirmed” in both letter and reality.

Since the Sparrow decision, the Supreme Court of Canada has from time to time readdressed the reconciliatory objective of section 35(1). From its focus in Sparrow on the reconciliation of federal power with federal duty, the Court held six years later in R. v. Van der Peet that “the aboriginal rights recognized and affirmed by s. 35(1) must be directed towards the reconciliation of the pre-existence of aboriginal societies with the sovereignty of the Crown.” In Haida Nation v. British Columbia (Minister of Forests), the Court held that in this area of the law, reconciliation is “not a final legal remedy in the usual sense”; instead it is “a process flowing from rights guaranteed by s. 35(1).” Finally, the Court in Mikisew Cree First Nation v. Canada (Minister of Canadian Heritage) held that the fundamental modern objective of section 35(1) is “the reconciliation of aboriginal peoples and non-aboriginal peoples and their respective claims, interests and ambitions.” The development of the reconciliatory objective of section 35(1) by the Supreme Court of Canada since Sparrow has resulted, according to Charlotte Bell, in the gradual imputation of a “much broader objective” to the provision. Bell argues, however, that the purpose of section 35(1) is “limited to setting parameters around the Crown’s ability to infringe or extinguish Aboriginal rights” and that the scope of the provision “may not be sufficient to permit the courts to accomplish the reconciliation of the claims, interests, and ambitions of the Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal peoples of Canada.” Prior to Confederation, the British Crown assumed the responsibility “to define and reconcile the relationship between First Nations and others” by ensuring the welfare and protection of Aboriginal peoples in the face of colonial expansion. This responsibility of the British Crown found its inheritor in the federal Crown at Confederation by virtue of section 91(24) of the Constitution Act, 1867. In order for this broad duty to find relevance today, the understanding of what constitutes the welfare and protection of Aboriginal peoples must adapt itself to the reconciliatory objective of section 35(1) of the Constitution Act, 1982. As sections 91(24) and 35(1) must be read together, so must their underlying rationales.

Since the Sparrow decision, there has been an obvious silence by the Supreme Court of Canada on the relationship between sections 91(24) and 35(1) that has inadvertently caused section 91(24) to appear irrelevant in the post-1982 era of Crown-Aboriginal relations. Perhaps the silence persists because the Supreme Court felt that it sufficiently enunciated the federal power-duty relationship in Sparrow, or because the modern role of section 91(24) as prescribed in this work has been implied by the reasoning of the Court ever since. Either way, the modern function of section 91(24) must be reasserted and reaffirmed. In Sparrow, the Court held that for federal power to be reconciled with federal duty, “the best way to achieve that reconciliation is to demand the justification of any government regulation that infringes upon or denies aboriginal rights.” It is possible to recast this statement with the language used in Haida Nation 14 years later, where a unanimous Supreme Court of Canada held that unresolved Aboriginal rights protected by section 35(1) must cross the divide into legal existence; it is incumbent upon the Crown that these rights be “determined, recognized and respected” through honourable “processes of negotiation.” If one reaffirms in Haida Nation the principle that federal power under section 91(24) must be reconciled with the federal duty to act in a fiduciary relationship with respect to the Aboriginal peoples of Canada, the “best way to achieve that reconciliation” is to obligate the federal Crown in its capacity as the provider of the welfare and protection of the Aboriginal peoples of Canada to diligently pursue honourable processes of negotiation to determine these rights. In Haida Nation, Chief Justice Beverley McLachlin pointedly stated:

Put simply, Canada’s Aboriginal peoples were here when Europeans came, and were never conquered. Many bands reconciled their claims with the sovereignty of the Crown through negotiated treaties. Others, notably in British Columbia, have yet to do so. The potential rights embedded in these claims are protected by s. 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982. The honour of the Crown requires that these rights be determined, recognized and respected. This, in turn, requires the Crown, acting honourably, to participate in processes of negotiation.

This truth must remain at the forefront in the quest for mutual reconciliation of Crown sovereignty and prior Aboriginal sovereignty in Canada. Otherwise, Canada will not accomplish the recognition and affirmation of Aboriginal and treaty rights promised by section 35(1) of the Constitution Act, 1982. The time for indifference and inactivity has passed; the time for recognition and reconciliation has come.

For the first annual Policy Options Constitutional Affairs Essay Competition, we received 27 entries from 11 university law schools across Canada. This entry was the runner-up.

Photo: GTS Productions / Shutterstock