At 6.00 a.m. on the second Monday of the spring campaign, Jim Flaherty was at the Pickering GO station, meeting commuters on their way to work in Toronto. From 905 to 416, the two area codes making up the Greater Toronto Area which would on May 2 deliver the long-sought Conservative majority.

At the finance minister’s side was Chris Alexander, the former Canadian ambassador to Afghanistan, and star Conservative candidate against Liberal incumbent Mark Holland in the riding of Ajax-Pickering, whom he would go on to defeat by six points.

At the two entrances of the station, Alexander’s volunteers handed out his campaign pamphlet to voters and asked if they wanted to say hello to Flaherty and the candidate. Herding cats. Sleepy cats.

“Come and meet our finance minister,” Alexander said over and over again.

“Nice to meet you,” Flaherty said. “How are you doing today?”

“Keep up the good work,” several voters told him. “You’re doing a great job.”

Two GO bus drivers actually got off their buses to come over and shake Flaherty’s hand. You don’t see that every day.

“How does it feel here?” Flaherty was asked

“Good, very good, maybe too good,” he said. “It feels like 1995 at Queen’s Park.” The year of Mike Harris and the Conservative sweep that ousted the NDP government of Bob Rae, the only man ever to have days named after him for the wrong reasons.

In the final days of the 2011 campaign, with the spectacular rise of the NDP in Quebec, bad memories of a disastrous NDP government would help Stephen Harper close the deal for a national majority in Ontario.

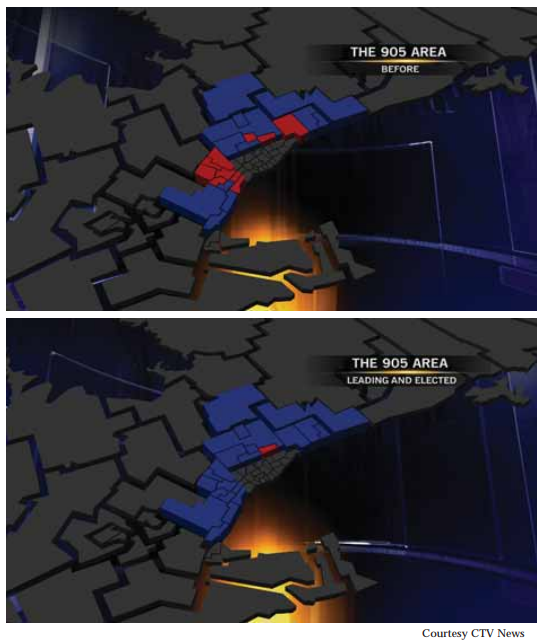

The Conservatives would elect 22 new MPs from Ontario, 73 in all, up from 51 in the last House. But it was the GTA that produced the majority. Where the Conservatives held 11 seats in 905 at dissolution, they would win 21 out of 22 on election day. And where they had no seats in 416, and hadn’t won a seat in the city since 1988, they won 9 out of 23 seats in Toronto itself.

In all, the Conservatives gained 19 seats in the GTA, taking them across the majority threshold. Overall, the Conservatives won 166 seats, 11 more than required for a majority, up from 143 in the last House. The Liberals, who had 32 GTA seats before the election, were left with only seven. Their leader, Michael Ignatieff, lost his own 416 seat of Etobicoke Centre.

And the Conservatives, astonishingly, are now the GTA party.

When the election was over, Flaherty convened a GTA caucus meeting at the ministers’ regional office in downtown Toronto. “We couldn’t fit everyone around the table in the boardroom, there were members who had to stand,” he said later. “We used to meet in a phone booth.”

For the Conservatives, the road to a majority always ran through 905. To their own surprise, it also ran through 416, where their best case in the war room before the election was that they might win four or perhaps five seats. Nine seats in 416 was way beyond their expectations.

The Conservatives’ sweep of 905 began in the banquet halls of its multicultural communities. The first messenger was Immigration Minister Jason Kenney, who had spent several years flying into ethnic dinners in Toronto. And the message was that Conservatives shared their entrepreneurial spirit and family values, while the Liberals had, for far too long, taken their votes for granted.

The second messenger was Flaherty, the popular finance minister who himself represented the 905 riding of Whitby-Oshawa and was minister responsible for the GTA. He campaigned tirelessly up and down the 401 and 407, with a few side trips into the city on the Don Valley Parkway.

In the final days of the 2011 campaign, with the spectacular rise of the NDP in Quebec, bad memories of a disastrous NDP government would help Stephen Harper close the deal for a national majority in Ontario.

And the third messenger was Harper himself, pouring it on in the final days of the campaign, charging through Ontario, warning of the dangers of an opposition coalition, one now led by the NDP, with Ignatieff reduced to the role of passenger in the back seat.

In the last five days of the campaign, when he pivoted from the Liberals to the NDP, Harper finally proved he had the stamina and the smarts to be a closer. On May 1, as part of a cross-Canada sprint on the final day of the campaign, he delivered a strong stump speech in London, where the Conservatives would unexpectedly win all three seats in the southwestern Ontario city.

“The choice in this election is increasingly stark,” he said. “You can have an NDP government or a Conservative government.”

He continued: “In this election, Mr. Ignatieff has taken the Liberal Party away from its roots, and in an NDP direction…so let’s be clear, a vote for the NDP is a vote for an NDP government. And a vote for the Liberals is now a vote for an NDP government. And let me speak very clearly to traditional Liberal voters. I know that many of you do not want NDP economic policies, that you do not want NDP tax hikes, and that is why to make sure the next Parliament does not raise taxes, Canada needs a stable, Conservative majority government.”

While some Ontario Liberals switched to the NDP to prevent Harper from getting a majority, many more Blue Grits voted for the Conservatives to make sure he got one. In the final five days of the campaign, the Liberals plummeted six points in Ontario in the Nanos daily tracking poll, while the Tories got a ballot box bounce on election day, as voters streamed to the polls to block an NDP-led coalition. Martha Hall-Findlay, a popular and personable Liberal MP, defeated in her 416 riding of Willowdale, later called it a “double whammy,” saying she got “squeezed from both sides.”

Call it the reverse echo effect, which attested to the influence of the polls. Reading the polls and coverage of the Orange Wave in Quebec, Ontarians thought it was a very good thing for Canada that Smilin’ Jack Layton and the NDP were taking down the Bloc. But they wanted no part of an NDP-led coalition to defeat a Conservative minority government. So, thanks to Layton’s historic gains in Quebec, the voters handed Harper his majority in Ontario.

You could feel it on the doorsteps in a new subdivision in Flaherty’s riding on Easter Saturday. First-time homeowners, many of them too young to remember Rae Days, spontaneously told Flaherty that “you have to get a majority to stop the NDP.” They’d heard about the accidental and disastrous NDP government from their parents, and the best thing about that from the Conservative perspective was that Rae himself was still around — as a Liberal.

On election night, the numbers turned up perfectly for the Conservatives in Ontario. They won 44 percent of the Ontario vote, while the Liberals and NDP were virtually tied at 25 percent. Harper couldn’t have scripted better splits than that, resulting in 73 Conservatives, 22 New Democrats and only 11 Liberals across the province.

Thus was born the Harper Coalition, Ontario and the West, which may only be solidified in future elections, as the Conservatives bring forward electoral redistribution to expand the House from 308 to 338 seats, all of the new ones in Ontario and the West.

As Conservative Senate Leader Marjory LeBreton later noted: “West of the Ottawa River, we won 48 percent of the vote.”

For the Liberals, as they surveyed the wreckage of their campaign, the numbers were eloquent. It was easily their worst showing in history, both in share of the popular vote and seats in the House. Their worst previous share of the pop-vote was 26 percent under Stephane Dion in 2008. Ignatieff won less than 19 percent in 2011.

And their worst previous score in terms of seats was 40 under John Turner in the Mulroney landslide of 1984, in what was then a 282-seat House. Ignatieff’s Liberals won only 34 seats in a 308-seat House, numerically and proportionately a much worse score than even the Turner debacle. The Liberals find themselves, for the first time in history, the third-place party in the Commons.

To go along with their 11 seats in Ontario, the Liberals won only four in the West, seven in Quebec and 12 in the Atlantic, and none in the three northern territories. And this from a party that in 2000, only a decade ago, won more than 100 seats out of 106 in Ontario because of the splits on the right between the Canadian Alliance and the Progressive Conservatives.

Given the Liberals’ standing as the most successful brand in Canadian politics in the 20th century, it was as if McDonald’s had suddenly fallen to third place in fast-food in the 21st century. Except that it didn’t happen overnight. It happened over three decades of neglect of the most storied political franchise in Canadian history.

This was the party that, just three decades ago, won 74 out of 75 seats and 68 percent of the votes in Quebec, in the exceptional circumstances of the prelude to the first referendum, where Quebecers wanted Pierre Trudeau as their federalist champion.

In 2011, the Liberals were reduced to seven seats and only 14 percent of the vote in Quebec, all of those seats in non-francophone ridings on the island of Montreal.

Given the Liberals’ standing as the most successful brand in Canadian politics in the 20th century, it was as if McDonald’s had suddenly fallen to third place in fast-food in the 21st century. Except that it didn’t happen overnight. It happened over three decades of neglect of the most storied political franchise in Canadian history.

Two events in the fall of 1980 would have long-term disastrous consequences for the Liberals. The first was the National Energy Program, which left the Liberals out of the game in the West from that day to this. And the second was the failed First Ministers’ Conference on the Constitution, which ultimately led to patriation with the entrenched Charter of Rights in 1981 and 1982, over the objections of Quebec, principal home to one of Canada’s two official language communities. Or as Trudeau himself described Quebec at the time: “Le foyer principale du Canada francais.” The patriation of the Constitution was followed by the death of the Meech Lake Accord in 1990, a seminal moment in which the principal negative actors were

Trudeau and Jean Chrétien. The demise of Meech gave birth to the Bloc Québécois, which Lucien Bouchard led to 54 seats and 49 percent of the vote in the 1993 federal election. This was followed by the blowback of the 1995 Quebec referendum, which in turn begat the federal waving of the Canadian flag that resulted in the sponsorship scandal and the Gomery Commission. This sustained the Bloc’s narrative of grievance in the 2004 and 2006 elections.

The Conservatives’ self-inflicted wounds in 2008, over cultural cuts and kiddie crime, enabled the Bloc to get through that campaign with 49 seats, even though its popular vote fell to 38 percent from 49 percent in 2004 and 42 percent in 2006.

The declining trend line of the BQ should have been a signal that the Bloc brand of poutine stands was in trouble in 2011. A party born in grievance had no narrative of grievance. Gilles Duceppe got away with it for a while, but he proved in 2011 to be not only tired and old, but totally tone deaf to the voices of his own people.

And in a single sound bite in a speech to a Parti Québécois policy convention in Montreal on April 17, Duceppe created the surge that took Jack Layton and the NDP all the way from the low 20s in the Nanos daily tracking poll to the mid-40s on election day, the point where the rising tide lifts all the boats, electing 59 members of the NDP in Quebec, to only seven for the Liberals, five for the Conservatives and four for the BQ.

“We have only one task to accomplish,” Duceppe said at the PQ convention. “Elect the maximum number of sovereignists in Ottawa and then we go to the next phase — electing a PQ government. A strong Bloc in Ottawa. The PQ in power in Quebec. And then everything again becomes possible.”

Et tout redevient encore possible. This was a direct echo of the PQ slogan in the 1995 referendum campaign, Oui, et tout devient possible. Duceppe would lose his East End Montreal seat of Laurier-Ste.-Marie by more than 5,000 votes and more than 10 points to the NDP’s Helene Laverdiere, a retired official from the Foreign Affairs department. Layton himself campaigned in the riding on Easter Saturday, pulling nearly 2,000 people to a rally without bussing anyone in.

It was the GTA that produced the majority. Where the Conservatives held 11 seats in 905 at dissolution, they would win 21 out of 22 on election day. And where they had no seats in 416, and hadn’t won a seat in the city since 1988, they won 9 out of 23 seats in Toronto itself.

Duceppe was playing the separatist card at a separatist meeting, and while it might have played well in the room, there was a much larger audience that was appalled by the prospect of another referendum that would divide Quebecers and perhaps break up the country. To make matters worse, Duceppe brought out Jacques Parizeau to campaign with him a week later. Duceppe might as well have campaigned with the ghost of Leonid Brezhnev in the streets of Moscow. Parizeau personified all the bad memories of the 1995 referendum.

Quebecers might show up for another referendum, but that didn’t mean they wanted one.

So what did they do? They went, spontaneously, to Jack Layton, le bon Jack, a good guy. Layton had been growing in the Nanos tracking poll, from the mid-teens at the outset of the campaign, through a four-point bump after his appearance as a gars sympa on Tout le monde en parle, the RadioCanada talk show that draws up to 1.8 million Quebecers on Sunday night, an audience bigger than Habs hockey, even in the playoffs.

Quebecers saw and heard that Layton had won the English-language debate on April 12 with Michael Ignatieff, delivering a haymaker on the Liberal leader’s poor attendance in the House. It played into the French language debate the following night, where Layton more than held his own with Duceppe. Replying to Duceppe’s argument that neither one of them could become prime minister, Layton responded, with a smile, that this was rather arrogant on the part of the BQ leader.

Though this was Layton’s fourth national campaign, he succeeded in reinventing himself in Quebec. While his French was imperfect, his accent was colloquial. Layton reminded Quebecers, especially by showing up in a Canadiens sweater during the playoffs, that Montreal was his team, as well as his home town, despite having spent decades in Toronto. In a matter of weeks, he became a favourite son in Quebec, the most powerful card in the deck of Canadian politics in that province.

Quebecers caucused over their choice au tour de la table de la famille on Easter weekend, a week before the vote. They decided that Jack was indeed their guy. And that they were going to vote for him. In the last week, the trend to the NDP in Quebec became as hard as the boards at the Bell Centre.

From 23 percent in the Nanos tracking poll on the day of Duceppe’s disastrous speech, the NDP grew to 43 percent in Quebec on election day. Meanwhile, the Bloc plummeted from 39 percent on April 17 to 23 percent on May 2, a loss of more than a point a day. In previous elections, the Liberals and then the Conservatives in 2006 had benefited from polarization as the default choice of federalist voters as the Block the Bloc party. But none of the federalist parties played that card in 2011. The voters decided to Block the Bloc entirely on their own.

As a result, the Bloc was reduced to a rump of only four seats, losing its standing as a recognized party in the House. Not only did the Bloc lose staff and research funding, it lost its place in question period. Where it used to have three or four questions a day, its small deputation, sitting as private members, will be fortunate to get one question every couple of weeks. And it will lose the federal subsidy of $2 per vote on which it has subsisted for years. Having received 1.7 million votes as recently as 2004, it won only 889,000 in 2011, nearly one million fewer votes in Quebec.

Where did the Liberal campaign sliding from a peak of 32 percent at the end of March in the Nanos daily poll to a historic nadir of 18.9 percent on election day? The answer is everywhere and in every way.

For openers, the Liberals forced an election Canadians didn’t want, over an issue, contempt of Parliament, about which voters were generally indifferent. They had a message that couldn’t be sold, and a messenger, Ignatieff, who couldn’t sell it.

“You know how many questions I got at the door about contempt of Parliament?” asked Conservative cabinet minister John Baird, who was reelected in Ottawa West-Nepean. “Four. Exactly four questions. I got six questions on the long form census, because it’s Ottawa. And I got 30 complaints about changes to a local bus route.”

The Liberal frame of contempt was also counterintuitive in the sense that Harper had managed his way through two minority Houses in five years, and that Flaherty had successfully steered five consecutive budgets through minority Parliaments, including one in the midst of the steepest synchronized global recession in 60 years. Harper had a simple ballot question, majority or minority, words that had been banned from the Conservative vocabulary in his previ-ous three elections. And Ignatieff was dogged from the beginning by hypothetical questions about whether he would bring down a Conservative government and form an opposition coalition. Roll the video of the Three Stooges Coalition from 2008. This played right into Harper’s narrative and framed his ballot question.

Ontarians thought it was a very good thing for Canada that Smilin’ Jack Layton and the NDP were taking down the Bloc. But they wanted no part of an NDP-led coalition to defeat a Conservative minority government. So, thanks to Layton’s historic gains in Quebec, the voters handed Harper his majority in Ontario.

There was also an element of institutional entitlement in Ignatieff proposing another frame, that of “a red door or a blue door,” when as it turned out, there was also an orange door.

For the first half of the campaign, hardly anything moved. “Another day when I wake up to see that Nik Nanos has the Conservatives 10 points ahead,” said former Prime Minister Brian Mulroney, who from the beginning of the campaign to the end privately predicted a Tory majority, though he warned that “anything can happen in the debates, as I know from my own experience.”

What happened is that Ignatieff took one on the chin from Layton over his poor attendance record. “If you want to be prime minister, you’d better learn how to be a Member of Parliament first,” Layton said. “You know, most Canadians, if they don’t show up for work, they don’t get a promotion. You missed 70 percent of the votes.”

Instead of replying that he was out meeting voters, doing his real job as Opposition Leader, Ignatieff stuttered and stumbled a lame reply that no one could remember. Ignatieff, the most experienced television performer and debater on the stage, was never in it after that. As a telling point — the Liberals had raised $3 million in the campaign up to the debates, but only $10,000 came in on the day after the English debate.

And then in his feature-length interview with CBC News anchor Peter Mansbridge the following week, Ignatieff allowed himself to be drawn into a discussion on the conditions under which he would form a coalition, the very question his advisers had implored him to avoid.

Mansbridge politely persisted, and Ignatieff finally went there. “All right, let’s run it out so we’re all clear,” Ignatieff said. “If Mr. Harper wins the most seats and forms a government, but does not secure the confidence of the House, and I’m assuming that Parliament comes back, then it goes to the Governor General, that’s what happens, that’s how the rules work. And if the Governor General wants to call on other parties or myself, for example, to try to form a government, then we try to form a government. That’s exactly how the rules work, and what I’m trying to say to Canadians, I understand the rules, I respect the rules, and I will follow them to the letter and I’m not going to form a coalition government and I’m prepared to talk to Mr. Layton or Mr. Duceppe or even Mr. Harper and say, Look, we have an issue and this is how I want to solve it. Here’s the plan that I want to put before Parliament. You know, this is the budget that we would bring in and then we take it from there.”

Game over. If the Conservatives couldn’t win a majority after a gift like that, which again played perfectly into Harper’s narrative, then they wouldn’t deserve one. There was an enduring and annoying professorial quality about Ignatieff. Here he was turning a dangerous hypothetical question into a lecture on constitutional convention, when his answer should have been “Ask the Governor General, I’m campaigning to lead a Liberal majority government.”

When the Liberal slippage reached the point where they were overtaken by the NDP in the polls due to the orange surge in Quebec, the bottom fell out of their campaign in Ontario. And in the closing stretch, the Liberals, who had always been the party of strategic voting, saw their voters in Ontario flock to the NDP and the Conservatives.

And there were two elections, the one in the bubble and the one on the ground. Trapped in the bubble, hunched over their BlackBerries sending tweets to each other, most members of the National Press Gallery missed the story on the ground. With rare exceptions such as National Post columnist John Ivison, who actually broke out of the bubble and went out on his own to talk to real live voters, most journalists travelling with the leaders were content to stay in the cocoon. There was the daily spat on Harper’s tour of how many questions he would take every day, when no one in the real world cared. Then there was the spectacle of the CBC’s Terry Milewski asking Harper if he was “a coward or a chicken” for declining a one-on-one debate with Ignatieff. It is impossible to imagine any member of the White House press corps being so disrespectful to the president of the United States. But then, journalism is the only profession in which inappropriate behaviour is not only tolerated, but encouraged.

On the ground it was very different from the bubble. Voters were angry about the election, and even knew how much it cost — $300 million that, as Flaherty would tell people at his many stops in 905, could be put to better use for taxpayers.

On the second Sunday of the campaign, Flaherty set out down the 401 from his home in Whitby to visit five 905 ridings, with a side trip into 416 for an evening fundraiser.

All five 905 ridings were held by the Liberals, three of them won by margins of five points or less. All of them were in play. Flaherty’s role was to fire up campaign volunteers to get out the vote.

“We are on the cusp of a majority,” Flaherty told a crowd of 500 at Parm Gill’s committee room in Brampton-Springdale. “It matters for the brilliant future of Canada that we have a majority.” Gill would beat Ruby Dhalla by 20 points.

At every stop, Flaherty openly campaigned on the “M” word that was not allowed to pass the lips of Conservative candidates in the last three elections.

And this led him to the prospect of an opposition coalition in the event the Conservatives were returned with a third consecutive minority government.

“They’ve done it before and they’ll do it again,” Flaherty said, recalling the Three Stooges Coalition. “What they tried to do was take over the government. The finance critic of the NDP sat in my office and said, ”˜You may be finance minister now but you won’t be in a week. We’re taking over.’

“We’ve come out of the recession in better shape than any other country in the world, with nearly half a million new jobs,” Flaherty continued. “We have a wonderful reputation in the world. Tim Geithner, the US treasury secretary, calls us ‘virtuous Canada.’ In the UK, they’ve had draconian cuts, with 400,000 civil servants laid off.”

The partisan crowds liked the narrative of Canada coming safely through the economic storm. It had the added virtue of being true, and told by the guy who was at the wheel.

“As a member of Parliament from the GTA, I get lonely in Ottawa,” Flaherty said. “We need more members from the GTA. It matters for the brilliant future of Canada that we have a majority.”

There was the “M” word again.

Down in Mississauga South, Stella Ambler was running against long-time Liberal incumbent Paul Szabo. He won last time by less than five points. Ambler would beat him by 10 points.

“I’ve had Jim as a boss,” said Ambler, who used to run his Toronto ministerial office. “But I’d love to have him as a colleague.”

“This is a riding we should win,” Flaherty said on the drive back into Toronto for a Rosedale fundraiser for Mark Adler. In York Centre, the Jewish vote was on the move to Harper because of his staunch support for Israel. “The Jewish vote is 24 percent of the riding,” said Adler, grandson of a holocaust survivor. “And 70 percent of it is coming to us.” On election day he would beat hockey legend Ken Dryden by 15 points.

Flaherty visited six ridings that day, and the Conservatives would win every one of them. And in Liberal Fortress Toronto, the Conservatives would win the multicultural and Jewish vote, core constituencies of the Liberal Party, not by a little, but by a lot.

On the morning of the election, Flaherty looked at the last set of poll numbers and liked what he saw — the splits in Ontario that didn’t even capture the Conservatives’ ballot box bounce.

“We’re there,” he said. “We’re good. It’s a majority.”

And finally, Stephen Joseph Harper is the Prime Minister of a majority government.

Photo: Drop of Light / Shutterstock